[ad_1]

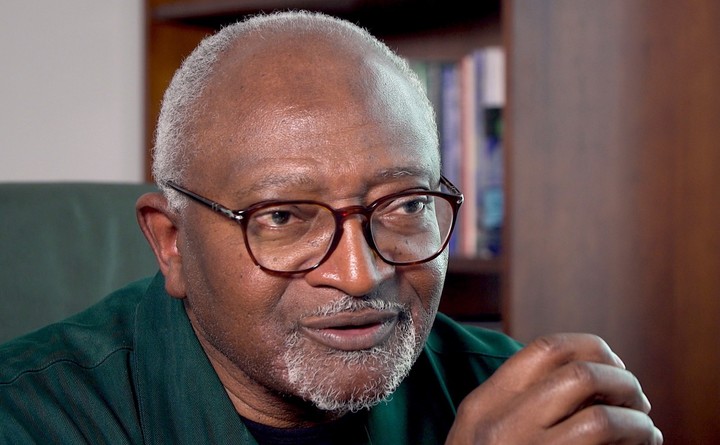

By Nexus Media, with Robert Bullard

The environmental movement is divided into two. Large, well-funded, green groups mostly led by white men, lead national campaigns and lobby Congress, while small, poorly funded environmental justice groups, largely staffed by people of color, work for change at the local level. Observers have written at length about this divide, arguing that is has hampered efforts to deal with climate change. Critics say that as long as these organizations operate in two separate spheres, big green groups will struggle to organize locally, and environmental justice groups will struggle to secure resources they need to thrive.

Dr. Robert Bullard, a professor of urban planning and environmental policy at Texas Southern University in Houston, believes that big green groups need to do more to support environmental justice groups, which treat pollution not as an isolated problem, but as part of a larger constellation of issues that includes poverty, discrimination and political marginalization. Bullard, known as “the father of environmental justice,” spoke with Nexus Media about the importance of local activism and what big environmental groups can do to strengthen the climate movement. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Nexus Media

In the climate movement, they talk about environmental injustice and climate change as two different challenges. Why do you say that is a problem?

When we in the environmental justice movement talk about the environment, we define the environment as everything. It’s where we live, work, play, learn, worship, as well as the physical and natural world. It’s very inclusive. And I think when we bring that frame to climate change, we see it in that same context, that climate change is more than parts per million and greenhouse gases.

The communities that are adversely impacted by pollution are the same communities that are on the front line of climate change. These are the same communities that host — in many cases without their permission — very dangerous facilities, very polluting facilities. They pump out lots of greenhouse gases, but they also pump out lots of other pollutants that make people sick.

The iconic figure for climate change is a polar bear. That’s very important in terms of what’s happening in the Arctic and what’s happening to polar bears, but for communities of color who have never been to the Arctic, who have never seen a polar bear in person, their iconic figure is a kid with asthma.

U.S. Marine Corps

You know, over the last four decades I’ve written 18 books on these issues. The central theme that brings all of those books together is equity and justice and fairness. If we neglect the least powerful and the most vulnerable, we run the risk of making it worse for everybody.

We saw that in Hurricane Katrina when we didn’t take care of the levees in the lowest-income communities. That’s obvious to many communities on the ground who are facing the ravages of climate right now. For them, it’s not a debate. It’s not theory. It’s real. For workers who work outside, they know it’s getting hotter. They know it’s more difficult to work outside, and they know that if it’s too hot to work, or if it’s raining every day, they can’t do their job, and they’re losing money. It’s not a matter of whether or not climate change is real. They know it’s real.

These communities who see it 24/7, they are real experts. They may not have gone to universities and gotten PhDs, but they have PhDs in living every day and in surviving the things that most people only write or read about or see on television. That’s where I think we have to really bring those voices to the forefront and get them integrated into decision-making. These people can tell you exactly what it’s like to survive a hurricane or live in a community that’s surrounded by all these dangerous facilities that are pumping out all kinds of pollution.

USDA

What are some examples of how climate change is exacerbating other social issues?

A flood or a hurricane can exacerbate housing issues. The communities that have resources bounce back. The communities that don’t have resources? It takes longer for them to come back.

The best and the most potent predictor of health and well-being in all of our cities across the country is a ZIP code. You tell me your ZIP code, and I can tell you how healthy are.

In South Philadelphia, you see all those big chemical plants. Here in Houston, you have refinery after refinery — the world’s largest concentration of refineries. Now, at what point do you add another, and people say, well, there’s too many? There’s nothing right now in the law that says this community is oversaturated.

The point is, once you get to 10 refineries, it’s easy to get 11, and that’s where people are saying, “Well, one more won’t make a difference.” That kind of thinking is archaic, paternalistic and racist. Because at what point would we even think about putting a chemical plant in Beverly Hills? But over in the south of LA, there’s chemical plant after chemical plant after chemical plant.

That kind of thinking evolves from this whole idea that communities of color and low-income communities make the best places for the things that other people don’t want. That is a classic case of environmental racism. We have said this and documented this over and over and over again with all kinds of studies. It’s not accidental. It’s not coincidental.

For certain communities, it’s seen as, “Well, it’s okay. They just have to live with it because that’s where the industry is located, and that community just happens to be located there.” But the communities were there first. It’s not a matter of chicken and egg.

U.S. Coast Guard

In some of these polluted communities, people say, “We would love to move, but our houses are worth nothing now.” They can’t sell.

That’s what environmental racism does. It steals wealth. This is a form of theft, of people’s wealth and of their health.

There’s a reason why we have such segregated neighborhoods in America. This is not natural and normal. It’s based on market forces and also based on political forces. For a long time in the southern United States, we had laws, and they had a name — they called them Jim Crow laws. There were neighborhoods where blacks couldn’t buy homes, certain neighborhoods where they were redlined, where they couldn’t get a loan, where they couldn’t get a mortgage. There were certain neighborhoods where there were no parks, and there were certain neighborhoods that had beautiful parks, but you couldn’t go to them.

We have to reverse those patterns of land use discrimination as well as the built environment discrimination. We have to reverse that because, if we don’t reverse it, we will rebuild after a disaster on inequality, and we will reproduce that inequality going forward.

A larger portion of black wealth is in home ownership. You know, 90 percent of our wealth is in our houses as opposed to white wealth, which is spread between houses and other property — businesses, stocks and bonds, mutual funds, all of that. If they lose their house, 45 percent of their wealth is still there. But, look at black families after Hurricane Katrina. They lose their house, and they’re losing 90 percent of their wealth if they can’t get their house back together.

Good Free Photos

Recent studies show that during recovery the communities that benefit most are white and affluent. Communities that are least able to benefit are mostly poor people and people of color. So that is a form of discrimination. The recovery should benefit all who lost, not just the affluent. And what we’re seeing in New Orleans right now is that median income has risen for whites, but for blacks, it’s either stagnant or it’s declined.

We’re in the South. We’re in the Gulf Coast. And the southern United States is unique. It has a unique history, a history of slavery, a history of fighting civil rights and integration. The southern United States is also the most environmentally befouled region in the country. And it’s also one of the most climate-vulnerable regions of the country. This area is tailor-made for a climate justice movement.

This should be ground zero for the most powerful movement around climate, around justice and those issues that converge. Now that’s what we’re trying to build. We’re trying to get people to understand that it’s imperative that we build this movement and that we fund this movement and that we grow this movement because this region will be the test case for the rest of the country.

Nexus Media

Are you seeing anything across the country that is encouraging?

It’s important that we acknowledge the fact that every social movement that has been successful in the United States has had a strong youth and student component, and young people today have started to own the issue of climate change, environmental justice and climate justice.

Millennials outnumber my generation, baby boomers. I’m optimistic that young people will take on this mantle and get the job done. My generation has taken it pretty far, but we have not gotten to the mountaintop. There’s so much work that still needs to be done, and there are so many wedge issues that drive us apart, and I think young people today are not perfect, but they have fewer wedge issues that drive them apart. That, to me, is very promising.

What do you think should be the role of the big environmental groups?

Our brothers and sisters [at the big environmental groups], they’re very smart, but they don’t know everything. They can learn from local movements, and they can learn from people on the ground.

We have to really be forward thinking in terms of how we’re going to build and grow our progressive movement to deal with these issues that we’re talking about — housing, energy, transportation, food security, health. We have to converge these issues. Climate change and energy and civil rights and environmental justice —it’s all wrapped together.

It is not by accident that the vast majority of environmental justice organizations are led by women. Many of those women — little old grandmothers, retired school teachers — said, “I’m fighting for my family, my home and my community.” They took the reins of environmental justice in these small organizations, and that’s how we have been able to get change. Think about what they could do if they were funded at a level commensurate with their need.

That’s how we build movements, really long-lasting movements across generations and across sectors and across issues, across race and class and gender. That’s how we are going to build a movement. We’re starting to see some of the [big environmental groups] come around, understanding that they can’t do this by themselves.

This interview was conducted by Bartees Cox. Nexus Media is a syndicated newswire covering climate, energy, politics, art and culture.

[ad_2]

Source link