[ad_1]

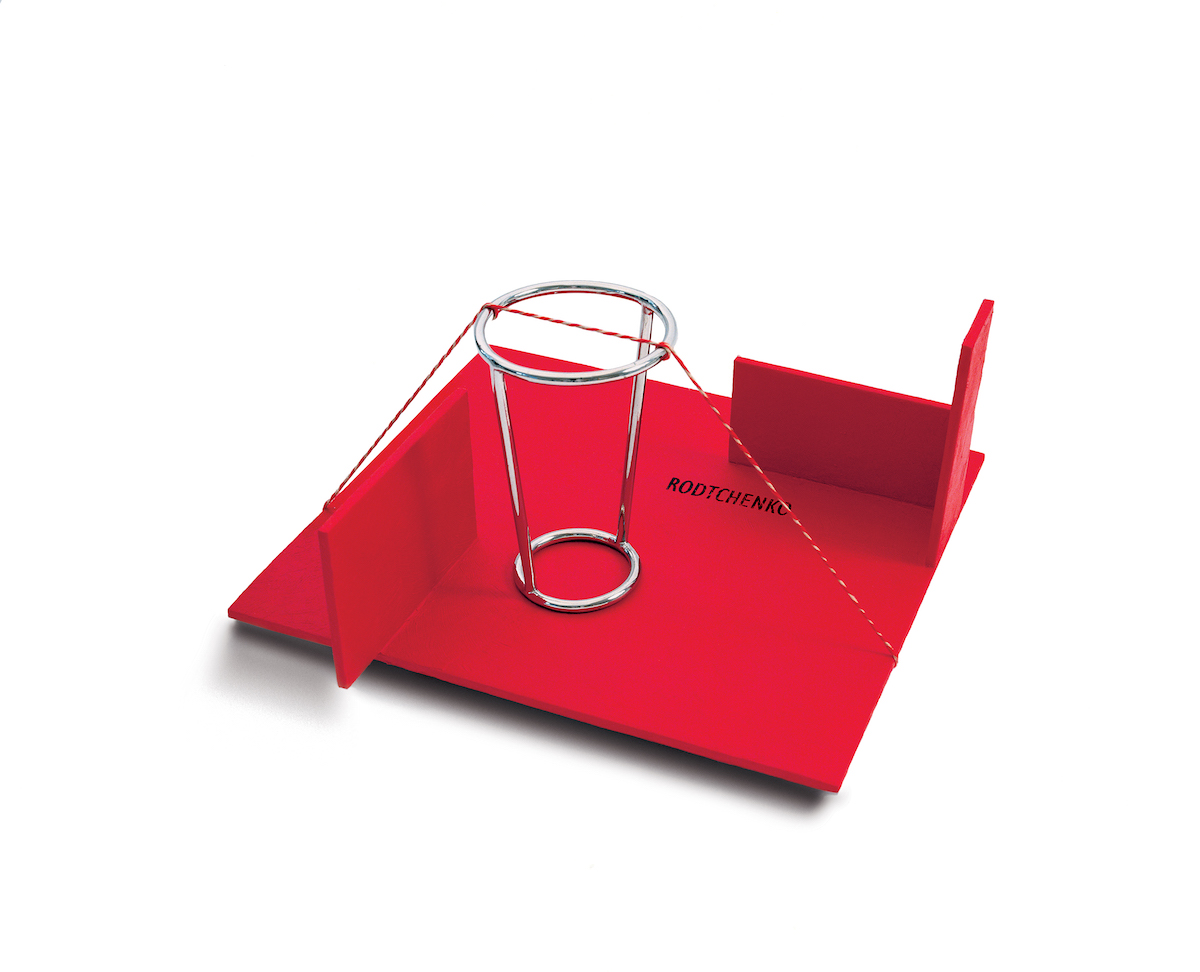

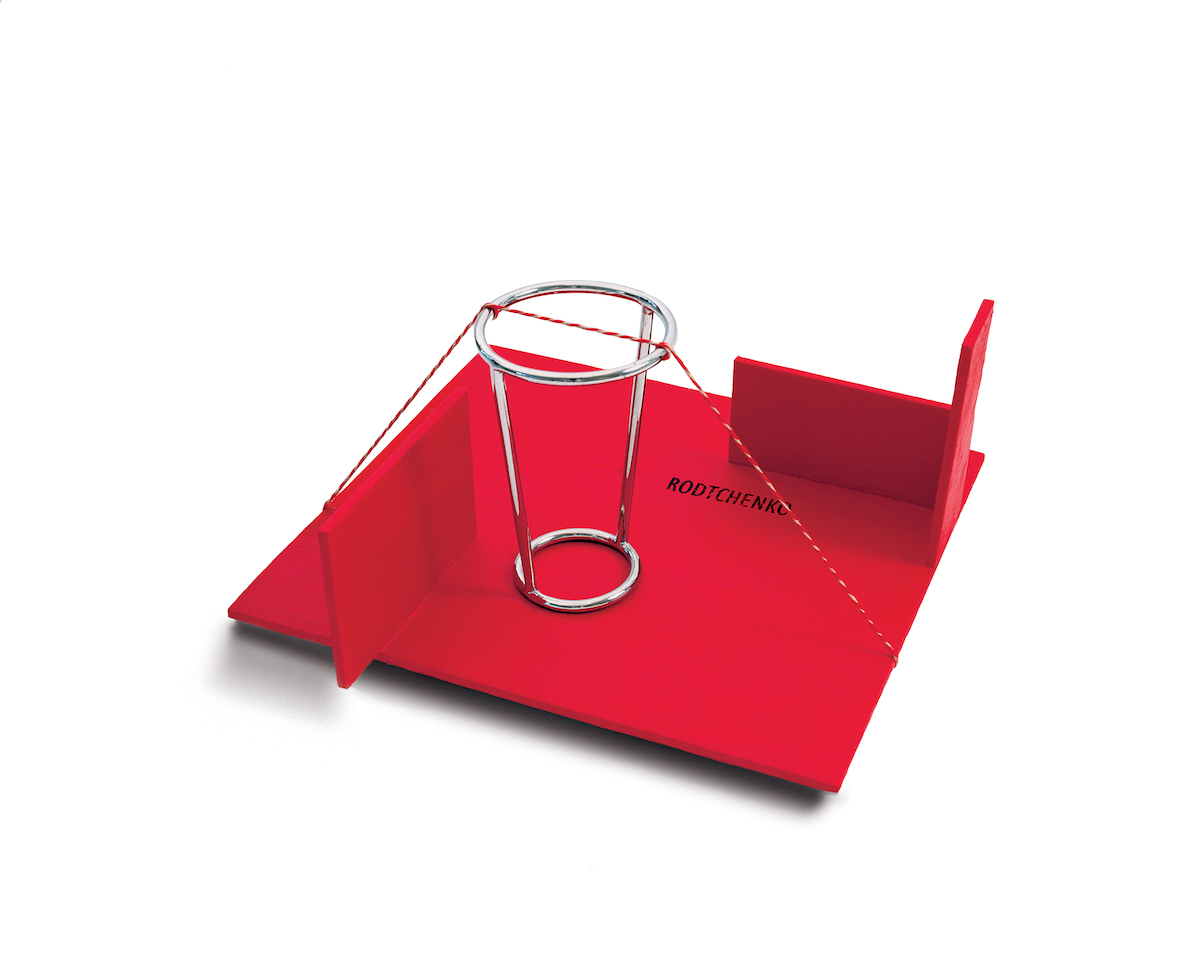

Waltercio Caldas, Rodtchenko, 2004.

VICENTE DE MELLO/COURTESY THE ARTIST

This year’s Bienal de São Paulo in Brazil is unusually broken into several mini-exhibitions, each curated by an artist. One of the shows is organized by Waltercio Caldas, best known for minimalist sculptures that meditate on the relationship between an object and its surrounding space. With that exhibition in mind, reproduced below is a profile of Caldas by Geri Smith that initially appeared in the October 1991 issue of ARTnews. In the piece, Caldas discusses his practice as well as the difficulties of being a Latin American artist in a Eurocentric art world. Smith’s article follows in full below. —Alex Greenberger

“The Mental Carpenter of Rio”

By Geri Smith

October 1991

Buses barrel down one of Rio de Janeiro’s busiest streets, drivers leaning on their horns as they narrowly miss jaywalking children. On one side of the street is a miserable hillside shantytown. Sidewalk vendors selling ice cream and tangerines fill the air with their cries. But if you dart across the street, talk your way past a security guard, and stroll down a narrow brick driveway, you leave behind the tropical urban chaos and enter another world, one whose order and precision offer a different kind of challenge to the senses—the studio of sculptor Waltercio Caldas.

Caldas was born and raised in Rio. During the ’60s he took art classes at the city’s Museum of Modern Art, one of the best places to get training in contemporary art at that time. Like most artists of his generation, he suffered through 21 years of repression under the military government and, more recently, six years of hyperinflation and economic shock programs that pummeled Brazil’s market for art. Yet the sculptor, who turns 45 next month, has remained remarkably detached from the confusion surrounding him. He even took it in his stride when an adolescent boy recently scaled his garden wall to see if there was anything inside worth stealing. “I took him by the arm and ushered him out the front door and then went back to drawing at my desk. I did momentarily think about the fragility of the world, however,” he says.

Twenty years ago Caldas won honorable mention in a competition sponsored by Rio’s Museum of Modern Art. His entry was a box lined in black velvet and containing a solitary sculpted figure wandering down a path in the darkness. Two years later, the museum gave him his first solo exhibition. The show was sold out before it opened, and Caldas was hailed by Brazilian critics and collectors as one of the most innovative and intelligent sculptors of his generation. Today Brazil is one of the strongest countries for sculpture in Latin America, but in the ’60s and ’70s the medium received little attention. Only now, more than two decades later, has Caldas won international recognition. He has been invited to exhibit at Documenta, in Kassel, Germany, next June, and some eight exhibitions of his work are scheduled over the coming year, including the current one at Gabinete de Arte, and another next month, at the Kanaal Foundation in Kortrijk, Belgium. In January, he’ll be in a large group exhibition, “To See America: The Netherlands and South America,” at the Koninklijk Museum in Antwerp.

Critics point to the mental carpentry that Caldas brings to his work, whereby the ideas behind the sculptures are as important as their physical representation. Caldas is concerned with the way an object “grasps its space.” He is intrigued by the concept the object’s position or by the surrounding air—either by changing the object’s position or by encouraging the viewer to imagine the movement. It’s a complex exercise in perception, whether the object is a glass of milk set inside a black iron tube or a framed series of dots displayed in maddeningly random order. Or a solitary gambling die trapped inside a block of ice, its whole reason for being—that tumbling of chance—frozen in place.

In his Curve (1986), a black granite disk is brilliantly illuminated over its top half and shaded underneath. The viewer focuses on a line separating the two qualities of light, the point where light and dark meet. “This object illustrates how I try for the same degree of absence and presence in each object,” Caldas explains. “It’s as if the line were a comma in a sentence.”

His work also calls into question the institution of art. At the 1983 Bienal in São Paulo he displayed 60,000 boxes of Chiclets and encouraged spectators to rush by the exhibit as quickly as possible, “to point out the industrial irony of the need thousands of people feel to go out and see thousands of things that are considered art.”

Caldas’ ground-floor apartment and atelier constitute a sanctuary where he can concentrate on his work. Putting some muffle classical music or jazz on the stereo to muffle the cries of his infant son, who is being comforted by his wife, Patricia, an architect, Caldas sits in a black leather chair at a large desk, and draws, sweeping away erasings with an antique mother-of-pearl clothes brush. “I don’t like to be condemned to work in just one place, though,” he says. Sometimes he escapes to the nearby mountains of Petropolis to work with stonecutters. Or he flies to São Paulo, where metalworkers fashion tubes, spheres, and iron rings according to his specifications.

Assembled objects find their way to a square gallery of sorts, just off the entrance foyer. On the walls are abstract line drawings from a recent exhibition, while resting on the floor is his 1987 sculpture Dissipator—a huge of polished-metal tubes set one atop the other in perfect balance. Maquettes of various works in progress are perched on a shelf. Caldas takes two or three years to complete a piece, going through what he calls a “decanting” process until he is satisfied.

Rio gallery owner Thomas Cohn, who is an admirer of Caldas’ work, calls him “one of the most interesting Brazilian artists of the last 20 or 30 years. There is an extra dimension, something magic, in his work that takes it beyond the conceptual.” And he was already doing this kind of work in the ’70s, long before foreign galleries were aware of him. In fact, many of the pieces Caldas exhibits overseas are from that period: “Our work is so unknown that sometimes in Europe I show objects I did 15 to 19 years ago, and it works,” the artist laughs. For the last 10 years he has been represented exclusively by the São Paulo gallery Gabinete de Arte, where the prices for his works range from $3,000 for a drawing to $20,000 for a large sculpture.

Caldas visits Europe and the United States regularly. Nevertheless, he chooses to work far from the major art centers. After a one-year stint in the mid-’80s in New York, where he was included in the 1984 show “Abstract Attitudes,” at the Center for Inter-American Relations (now the Americas Society), he was left with the impression that many artists in the United States are often more concerned with making a career than with making art. He appreciates Brazil’s more relaxed attitude toward art production. “In Latin America, we are outside the mainstream, so we can work without being jailed in a category. I like that,” he says.

The freedom to invent at his own pace maybe a key to Caldas’ success. “Waltercio is one of the most important Brazilian artists of his generation,” says Ronaldo Brito, a critic and professor of art history at Rio’s Catholic University who wrote a book about the artist, called Devices (1978). “He has a sort of post-Pop, contemporary intelligence that allows him to produce objects with an exactness that is not mathematical, but poetic,” Brito continues. “His work is a mixture of rigorousness with freshness, accessibility.”

A version of this story originally appeared in the October 1991 issue of ARTnews on page 98 under the title “The Mental Carpenter of Rio.”

[ad_2]

Source link