[ad_1]

Something is missing from the Morgan Library & Museum’s showing of the exhibition “Jean-Jacques Lequeu: Visionary Architect”: a suite of ink-wash images in which the eighteenth-century artist and builder manqué renders himself—a fat-faced, saucer-eyed Frenchman—dressed variously as a woman and as a little girl, staring expectantly at the viewer. The absence of Lequeu’s transvestite portraits, which are among the designer-draftsman’s most celebrated works, and of most of his explicit depictions of the human anatomy is conspicuous, the more so since many of these works were present in the show’s original iteration, at the Petit Palais in Paris in 2018–19. Seemingly an odd sideline for a trained architect, Lequeu’s sexual image-making is in fact key to his legacy, evidence of an artistic project sparked by revolution but ultimately, as architectural historian Anthony Vidler has written, “carried out in his bedroom.”

Lequeu’s life was marked by failure and frustration. Born in Rouen in 1757, he studied and worked in Paris before the Revolution, attaching himself to François Soufflot (nephew of the famed architect of the Panthéon), but besides the facade of a single hôtel particulier, it does not appear that Lequeu ever saw his own designs realized. He spent most of his career as a minor bureaucrat. Swept up in the turbulent events of 1789, Lequeu threw in with the revolutionaries, only to see his professional advance thwarted again, forcing him into retreat in his Right Bank flat and into a practice that combined the fervor of revolutionary belief with crankish solipsism. Fantastic proposal followed fantastic proposal: unrealizable monuments and civic temples, hermitages and altars and belvederes, as well as the irresistibly weird erotica, though after his death in 1826, this transgressive corpus was more or less consigned to oblivion.

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie.

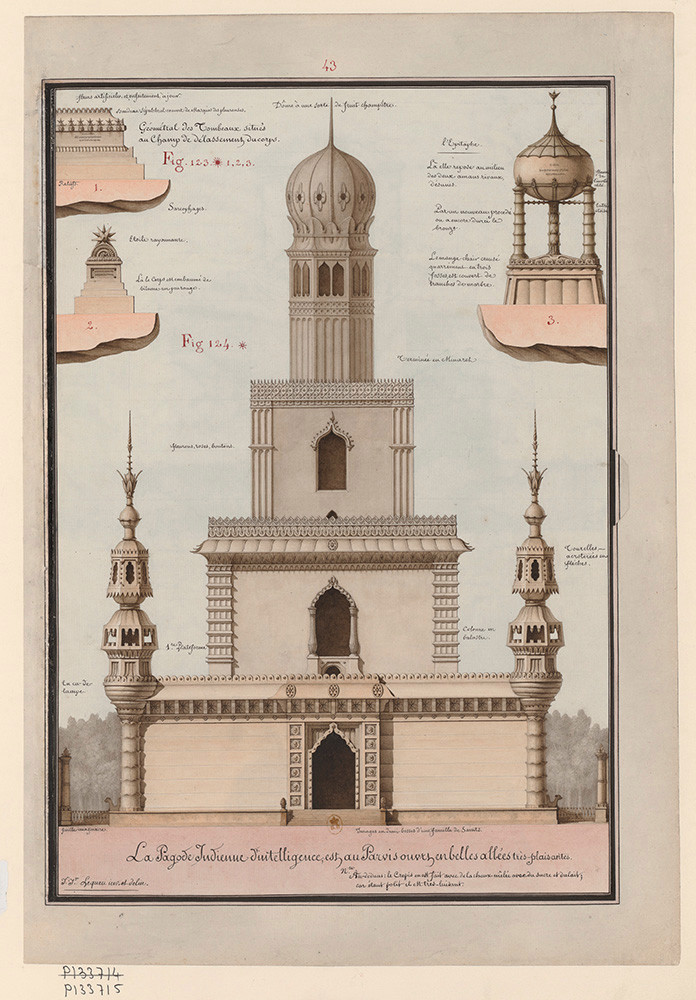

With Lequeu finally restored to something like the historical mainstream, it seems a shame to put so much of his work back in the closet. However, what is on display is quite astonishing enough: for instance, a design for a tomb for the Athenian orator Isocrates comprising a carefree-looking mermaid astride a giant stone sheep, or an Indian pagoda, complete with a dome to be shaped—as the architect describes it—like “country fruit.” A proposal for Lequeu’s own funerary shrine, a subterranean complex to be topped with a sculpture of the architect’s tools, bears a paper tab that can be lifted to reveal an alternative scheme for a massive cross, symbolic of the artist’s sufferings in the world of men. Worth the price of admission alone is Grotto of the Oceanids, an undated drawing of a kind of soggy basilica dripping with stalactites and drenched by shimmering cascades, as if Robespierre had taken over Disney’s Typhoon Lagoon.

Lequeu’s spicier catalogue isn’t altogether absent from the show’s current iteration. One drawing of female genitalia (The White Savage, 1779–95) hides demurely behind a special screen in the middle of the gallery—an appropriate setting, given its usual home in the Enfer, the section of France’s national library reserved for the licentious and the pornographic. Another compelling drawing, He Is Free (1788–99), features a nude woman popping partway out of a classical arch. Lying on her back, in the throes of some strange passion, she reaches for a tropical bird whose dangling tail feathers are unmistakably testicular. These are complemented by several of Lequeu’s physiognomic studies—self-portraits of the architect yawning, winking, and generally mugging—presumably intended as scientific examinations of different affective modes but coming closer, in effect, to surreal caricatures.

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Departement des Estampes et de la photographie.

This dualism—supreme rationalism and dreamy deviance—began to attract the attention of architects and historians in the twentieth century. In the 1930s, Viennese architectural historian Emil Kaufmann first unearthed Lequeu from his archival interment and placed him alongside Claude-Nicolas Ledoux as one of the Enlightenment-era architects who prefigured the advent of modernism. Three decades later, Lequeu was in vogue again, viewed as a tripped-out visionary and Sade-ian provocateur; in the 1980s, he was reinvented once more, this time by French academic Philippe Duboy, who spun a hallucinatory history in which the architect possibly never existed, but was instead invented by Marcel Duchamp and a group of artistic coconspirators. Farfetched as that may sound, it only goes to show how easily the long-dead designer lends himself to different ideological agendas and “taste moments,” to use Vidler’s phrase. Never at home in his own time, Lequeu has come to rest in ours, and will doubtless find the future still more congenial.

This article appears under the title “Jean-Jacques Lequeu” in the April 2020 issue, pp. 81–82.

[ad_2]

Source link