[ad_1]

I’ve been taking some virtual walks lately through vacant closed museums. By which I mean to say I’ve been scrolling through Google Arts & Culture tours, clicking in and out of museums in Milan and Los Angeles and Seoul, using the arrow keys to spin around and around galleries I’ll probably never visit in person.

As museums the world over shut their doors in response to an uncontrolled global pandemic, many are staying open virtually, posting Instagram stories, livestreams, YouTube lectures, and Twitter threads. Some are spotlighting Google Arts & Culture tours that were uploaded before the fact. Since 2011, Google has partnered with hundreds of cultural institutions around the world to digitize portions of their physical space and make them virtually trawlable. The tours use the same technology as Google Street View, which aims to map and photograph every street on earth. As of December 2019, the company claimed it had captured 10 million miles of imagery, from the house down to the block to sections of the Great Barrier Reef. The world of Google Arts & Culture falls under the umbrella of the Google Cultural Institute, which falls under the umbrella of Google, which falls under the umbrella of Alphabet, which is a very large umbrella indeed. Like Google Street View, the world of Google Arts & Culture exists somewhere between 2D and 3D: 360-degree panoramas stitched together into on-screen simulations of physical spaces.

In Google Arts & Culture’s “featured” category, I clicked on “Italy: All Roads Lead to Culture,” headlined by a zoomed-in video montage of gondoliers, marble fountains, the ceiling of the Sistine chapel, and a small church on a wheat-colored hill bracketed by cypress trees. I couldn’t help it: despite the easy sentiment, my heart swelled a little at the last image, which could be anywhere in Italy, but could also be a place where the death knells ring only once a day, so that they don’t ring constantly. Google invited me to explore various destinations. “Milan is for art lovers,” says one link, and as an art lover, I decided to click on Milan.

Courtesy Google Arts & Culture

I went into the Galleria d’Arte Moderna. I’ll admit I’d never heard of the museum, but Google told me it has an impressive collection of Italian and European works from the eighteenth to twentieth centuries, housed in a villa that once belonged to an Austrian count. I went through a courtyard, clicking my way impatiently past a lovely outdoor café, lush with flowers; in this world, it’s perpetual summer. I wondered how they got the museum empty enough in the middle of the day to capture it like this. In the first gallery I entered, there were some very white sculptures: busts, two lovers intertwined, a distinguished-looking man holding a quill pen. I could see wall text, but I couldn’t get close enough to read it. I navigated the room with my arrow keys, and suddenly I was very close to the heads of the kissing lovers. Then they were reversed, and I was accidentally in the next room, also filled with white sculpture, where I could read the wall text: “Cento Anni, Sculpture in Milan 1815–1915.” I learned, via Google search, that I was looking at an exhibition that had closed in December 2017, weirdly frozen in time on-screen.

There was almost no information. Sometimes the captions made me laugh a little: “This [collection] includes famous paintings and sculptures, living together within the walls of the museum.” Some of these tours are more informative, but I still found myself trying to Google objects based on their appearance, trying to find out what they were. Really, these aren’t tours at all, they’re better characterized as intensely random encounters. Suddenly, I zoomed in to a white spot on the wall, so close it was blurry. Suddenly, I was in a new room, filled with paintings, and looking sideways at a canvas that might or might not have been painted by Andrea Appiani. Suddenly, I was at an unmanned information desk. I was a little clumsy with the technology, certainly, but it’s also clumsy technology—not designed for looking closely so much as panoramically. Street View technology aims for a sort of overall sense of awe—the effect of a re-created space, rather than its details. A museum, I think, is oriented toward the details. My primary sensation on these tours is of the uncanniness of a world oddly stitched together. My secondary sensation is just dizziness. Still, if you accept that a Google Arts & Culture tour is nothing like walking through a museum, it has its own strange pleasures.

Courtesy Google Arts & Culture

I like the halting visual whoosh the screen makes as you zoom from one room to another. I like being stuck between frames: half a parking lot and half a gallery, one sliding up to reveal the other. I like spotting blur-faced people and cars outside the museums, more freeze-frame ephemera. If you press a single arrow key long enough, you can set a gallery to spinning like a top. Keep in mind that this might cause a rainbow pinwheel to appear on your computer screen and all your applications to quit, sending you back to square one—a reset of the whole adventure. Then you can go back to the museum and click, click, scroll your tentative and glitchy way through, maybe taking a different path this time. In another Italian museum, the Uffizi in Florence, I kept having a problem centering myself, so I would slam into windows like a confused bird. There are technical hiccups, too: upstairs in the Galleria d’Arte Moderna, a fire extinguisher appears in one frame, but as you get closer it fades into a red blur, an intentional but imperfect removal.

In another gallery, it seems Google accidentally blurred the faces in one of the paintings—a tactic the company uses in Street View as a sort of ad hoc privacy protection for people it has photographed. Sometimes Google Arts & Culture blurs paintings for copyright reasons, but this doesn’t seem to be the case here; the painting’s three faces are visible from most angles, but when you get close, they disappear. This strikes me as a perfect sort of malfunction, evidence of Google’s clumsy handiwork in piecing together a virtual museum world, a serendipitous error that could, depending on your mood, look like a very interesting piece of art.

SOME SHUTTERED MUSEUMS are operating different kinds of virtual tours on their own terms: lower on the tech, heavier on the information, easier to digest. Just before the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., shut down, curators and conservators began to record different spaces in the museum as quickly as they could—photos of artworks they like, and short videos of individual gallery spaces. Every day, the museum has been posting a single gallery at a time on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter, with commentary by curators.

Anabeth Guthrie, the NGA chief of communications, said their website saw a 400 percent increase in traffic in the first week the museum was closed. More than half the hits came from Spain and Italy. “We are of course thinking about the visitors who may not be able to tour our exhibitions in person, as well as the teachers who are leading classrooms virtually, parents looking for child-friendly activities, and audiences who are dealing with anxieties,” Guthrie said in an email. “This is a chance for us to connect meaningfully without audiences and show that we are more than the sum total of the art in our galleries.” This seems to me the crux of the issue for museums: what they can offer when they can’t offer their physical space.

I’ve been scrolling through the National Gallery of Art’s mini-tour Twitter threads most days since they first posted them. It’s not the kind of thing I would usually do. I tend to think Twitter threads, especially ones meant to be informative, are cheesy. And maybe these are a little cheesy, replete with hashtags like #MuseumFromHome and #MuseumMomentofZen. The video quality could be better, certainly. But I find it soothing in its simplicity.

I watched and rewatched the slow pan of what was probably an iPhone camera around the upper level of the east building, gallery 407B, which contains mostly Abstract Expressionist works. Joan Mitchell’s Salut Tom (1979) takes up a whole wall, four panels of yellow and blue and green, inspired by the memory of her view of the river Seine. Later, watching a close-up video, I noticed how much black there was in the painting. I also noticed the empty bench in the middle of the gallery—unoccupied, serene.

Maybe I’m overwhelmed by the possibilities of artistic content online right now. It feels like there’s glut of options to look at. This is always true, but all the more so when I can see art only digitally. Here’s something that feels manageable. It involves no choice and no complicated technology, basically mimicking the experience of walking into a random gallery at a random museum where I might go with my parents if we were in D.C. together, which is not a very likely scenario, but weirdly comforting. I like the slow pan of the camera circling a single gallery and back again.

I’ve also been looking at art that was made to be seen on a screen. Specifically, I’ve been visiting Olia Lialina’s best.effort.network, a more advanced iteration of a 2015 piece that was supposed to be unveiled at arebyte Gallery in London this March. The closed gallery is livestreaming an installation view of the empty room. No matter, really—it was designed to be viewed on a screen.

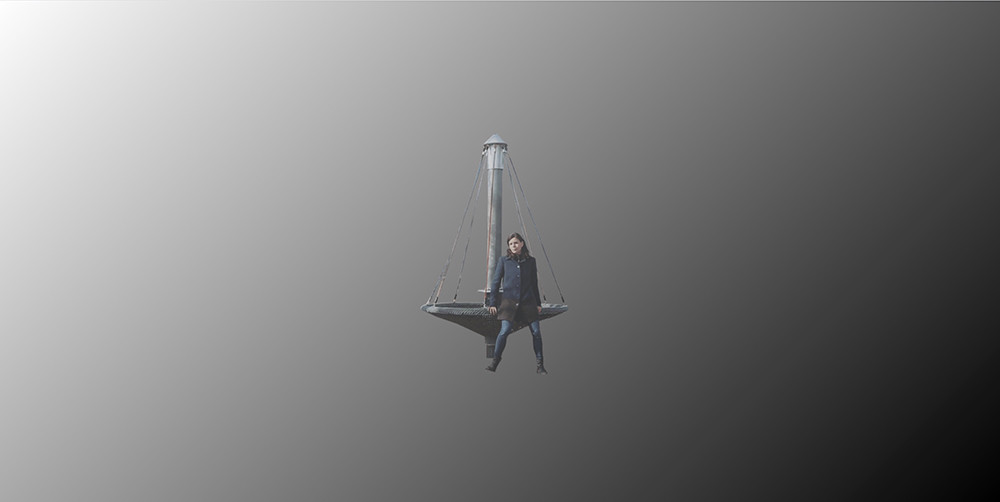

The conceit is simple. On the web page, an image of an old-fashioned carousel rotates against a ghostly gray background. After a few seconds or minutes, an animation of Lialina appears to sit the carousel’s edge, pushing her feet against the digital ground to make it turn. She disappears again after a few rounds. The animation can appear in one person’s browser at a time; she will reappear eventually, after she has drifted through all the other browsers that are waiting online. It’s oddly remarkable, this limitation—we are so used to the online version of our bodies having the capacity to be everywhere at once.

“If I’m somewhere, I’m nowhere else,” Lialina said about the piece, over a video chat a few weeks ago. “It’s a bit against the logic that you can make an endless [number] of corpuses.” We were talking in the days just before the whole world moved on to Zoom—before we were all confined to a single physical space as our image multiplied across many browsers.

I’ve been logging on to the piece daily. It has taken longer, lately, for Lialina to appear; maybe more people are seeking comfort in net art. But she always comes, eventually, and leaves, and returns. It’s a strange thrill to know that I’m the only one seeing her then, that she is on my screen alone. It makes the experience of digital art feel somehow material, more solid than the images of sculptures in closed museums. It’s also nice to know that when Lialina’s image disappears, someone else is looking at it, on another computer, in another locked-down room.

[ad_2]

Source link