[ad_1]

KATHERINE MCMAHON/ARTNEWS

Why do works by Vincent van Gogh look the way they do? Scholars have supplied all sorts of explanations, ranging from mental illness to lead poisoning, though one thing is for sure: his paintings look like something other than conventional everyday life. With a van Gogh blockbuster on view at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, we turn back to the April 1–14, 1942 issue of ARTnews, in which John Rewald kicked off a series that drew comparisons between famed paintings and photographs he’d taken of real-world locations that often looked little like artists’ painterly representations. “The views that van Gogh chose often amazed me by their banality, by their total lack of any emotional quality—that quality he makes so urgent in all of his works,” Rewald wrote at the time. The article follows in full below. —Alex Greenberger

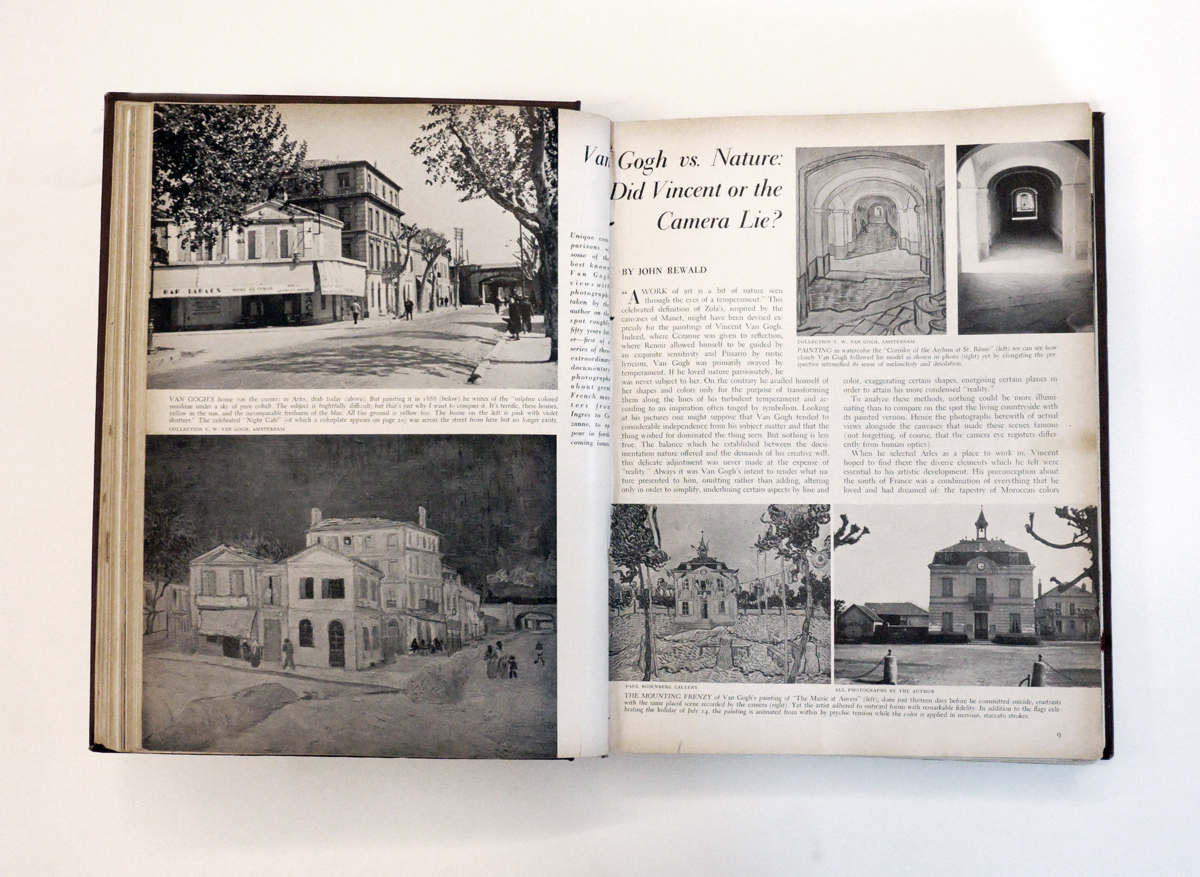

“Van Gogh vs. Nature: Did Vincent or the Camera Lie?”

By John Rewald

April 1–14, 1942

Unique comparisons of some of the best known van Gogh views with photographs taken by the author on the spot roughly fifty years later—first of a series of these extraordinary documentary photographs about great French masters from Ingres to Cézanne, to appear in forthcoming issues.

“A work of art is a bit of nature seen through the eyes of a temperament.” This celebrated definition of Zola’s, inspired by the canvases of Manet, might have been devised expressly for the paintings of Vincent van Gogh. Indeed, where Cézanne was given to reflection, where Renoir allowed himself to be guided by an exquisite sensitivity and Pissarro by rustic lyricism, van Gogh was primarily swayed by temperament. If he loved nature passionately, he was never subject to her. On the contrary he availed himself of her shapes and colors only for the purpose of transforming them along the lines of his turbulent temperament and according to an inspiration often tinged by symbolism. Looking at his pictures one might suppose that van Gogh tended to considerable independence from his subject matter and that the thing he wished for dominated the thing seen. But nothing is less true. The balance which he established between the documentation nature offered and the demands of his creative will, this delicate adjustment was never made at the expense of “reality.” Always it was van Gogh’s intent to render what nature presented to him, omitting rather than adding, altering only in order to simplify, underlining certain aspects by line and color, exaggerating certain shapes, energizing certain planes in order to attain his more condensed “reality.”

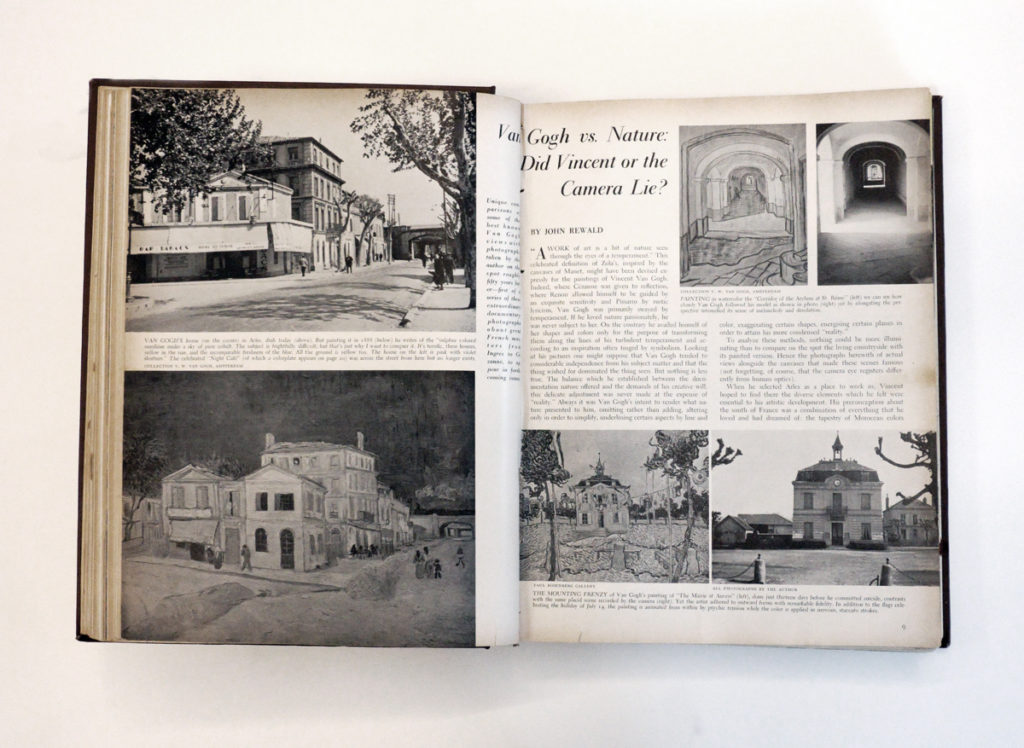

To analyze these methods, nothing could be more illuminating than to compare on the spot the living countryside with its painted version. Hence the photographs herewith of actual views alongside the canvases that made these scenes famous (not forgetting, of course, that the camera eye registers differently from human optics).

KATHERINE MCMAHON/ARTNEWS

When he selected Arles as a place to work in, Vincent hoped to find there the diverse elements which he felt were essential to his artistic development. His preconception about the south of France was a combination of everything that he loved and had dreamed of: the tapestry of Moroccan colors which Delacroix so admired, the incisive outlines of Japanese prints, lastly the actual shape of Provence as he had seen it in the canvases of Cézanne and Monticelli. Over and above this he was to discover, to his considerable surprise, that the country around Arles at times resembled his native Holland. But the color of the landscape impressed him even more than its character and it was its richness under the ardor of southern sunshine which carried him away and offered him new and absorbing problems.

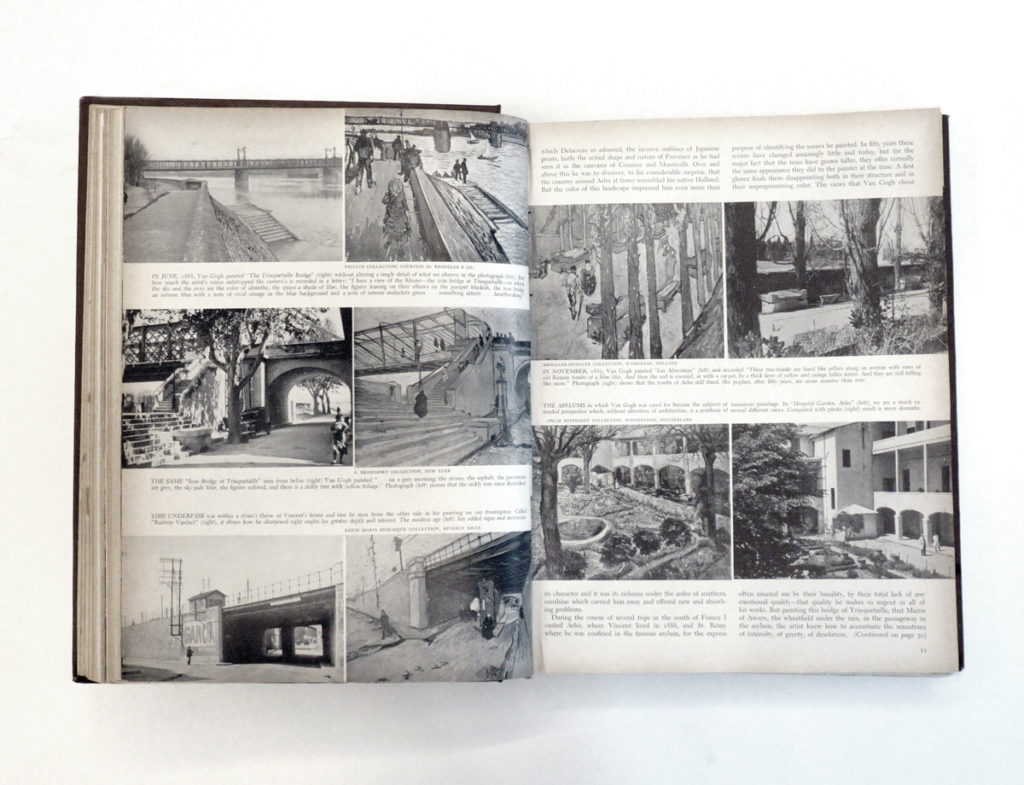

During the course of several trips in the south of France I visited Arles, where Vincent lived in 1888, and St. Rémy where he was confined in the famous asylum, for the express purpose of identifying the scenes he painted. In fifty years these scenes have changed amazingly little and today, but for the major fact that the trees have grown taller, they offer virtually the same appearance they did to the painter at the time. A first glance finds them disappointing both in their structure and their unprepossessing color. The views that van Gogh chose often amazed me by their banality, by their total lack of any emotional quality—that quality he makes so urgent in all of his works. But painting the bridge of Trinquetaille, that Mairie of Auvers, the wheatfield under the rain, or the passageway in the asylum, the artist knew how to accentuate the sensations of intensity, of gayety, of desolation or of melancholy which he discovered in them. By purely pictorial means he has stressed line and color (although the latter, unhappily, is not apparent in reproduction).

Faced with the themes and the canvases of van Gogh, so strangely alike yet so absorbingly different, one realizes that “reality” cannot exist independently, and that the artist paints after all not what is but what he sees. Vincent himself best defined the problem when he asked his brother: “When the thing represented is, in point of character, absolutely in agreement and one with the manner of representing it, isn’t it just that that gives a work of art its quality?”

[ad_2]

Source link