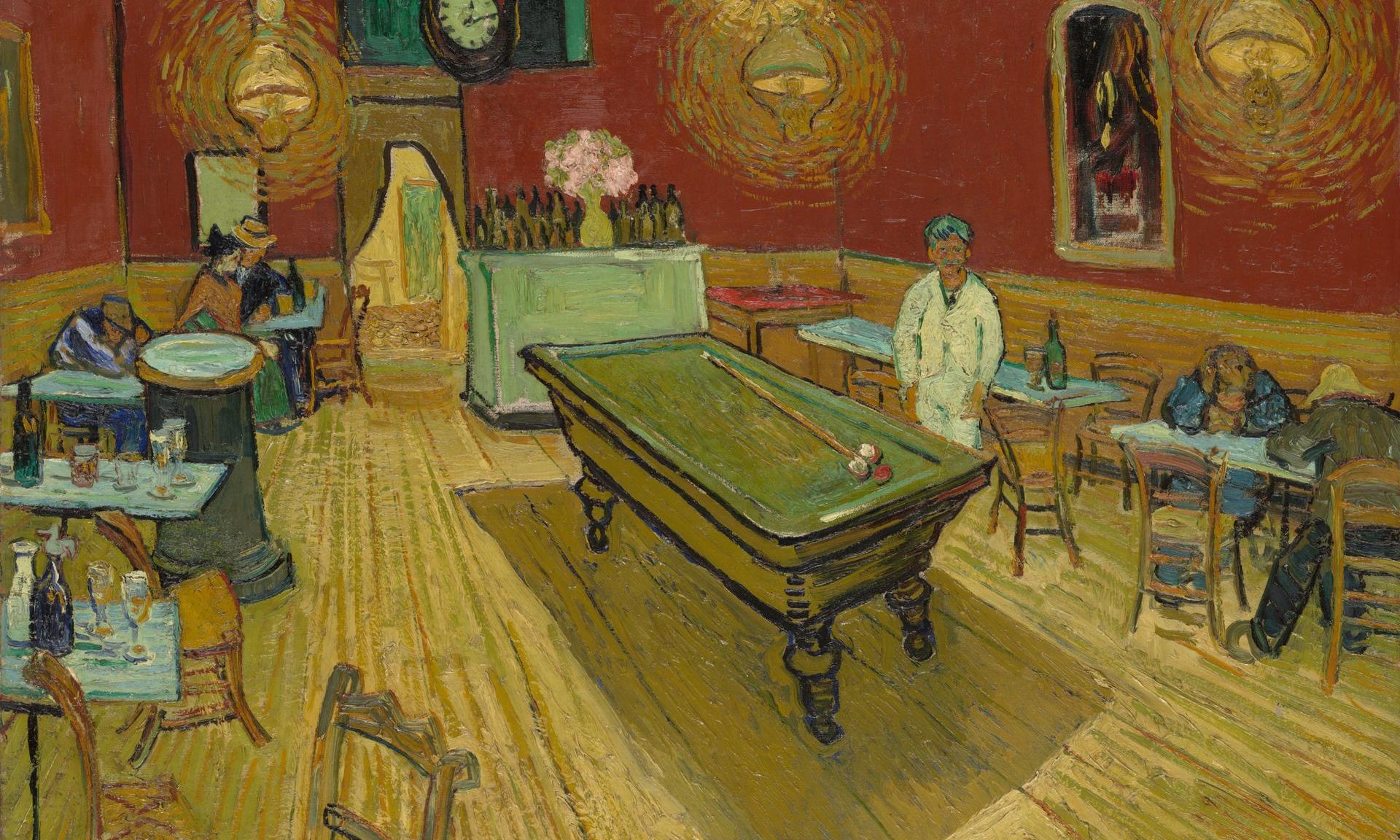

Van Gogh’s The Night Café (September 1888)

Credit: Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven; Bequest of Stephen Carlton Clark, BA 1903

Adventures with Van Gogh is a weekly blog by Martin Bailey, our long-standing correspondent and expert on the artist. Published every Friday, his stories range from newsy items about this most intriguing artist to scholarly pieces based on his own meticulous investigations and discoveries. © Martin Bailey

Among Van Gogh’s most intriguing Arles paintings is The Night Café (September 1888), depicting the Café de la Gare, where he would drink in the evenings, often with his friend the postman Joseph Roulin. He also lodged there from May to September 1888, in a small bedroom above the café.

Vincent described the haunt in a letter to his brother Theo: “It’s what they call a ‘night café’ here (they’re quite common here), that stay open all night. This way the ‘night prowlers’ can find a refuge when they don’t have the price of a lodging, or if they’re too drunk.”

Vincent claimed that he had stayed up three nights to do the painting, sleeping during the day, in order to capture its nocturnal atmosphere. He must certainly have observed the scene late in the evenings and done some work on the picture, but lengthy painting under gaslight might have been difficult.

Taking a vertiginous view, the billiard table, casting a dark shadow, is centre stage. The café’s owner, Joseph-Michel Ginoux, stands nearby in his white coat. Two months later Van Gogh painted a portrait of Ginoux, in rather more formal garb. The curious colours in the portrait suggest that it too may have been intended to capture a gaslight effect.

Van Gogh’s Portrait of Joseph-Michel Ginoux (November-December 1888)

Credit: Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

Around the edge of the cafe's room are tables and chairs, along with five inebriated late-night customers. A doorway at the back presumably leads to the kitchen and the staircase to Van Gogh’s bedroom. The clock above the well-stocked counter shows it is just after midnight. Unusually for Van Gogh, he signed the work (Vincent), in the lower-right corner, and even gave it a title: “Le café de nuit”.

At the back of the room a couple share a bottle, while three men doze (the one on the far right in the yellow straw hat, seen from behind, might represent the artist). As Van Gogh explained to his friend Emile Bernard, “it’s a house of assignation, and from time to time you see a whore sitting there at a table with her fellow”.

Van Gogh later complained to Bernard: “I’ve already written you a thousand times that my night café isn’t a brothel, it’s a café where night prowlers cease to be night prowlers, since, slumped over tables, they spend the whole night there without prowling at all.”

What was most striking for Vincent in his painting were the vivid hues, particularly the red walls, contrasting with the deep green ceiling. Using complementary colours, his aim was to convey a mood. As he wrote to Theo: “I’ve tried to express the terrible human passions with the red and the green… Everywhere it’s a battle and an antithesis of the most different greens and reds.” It is unlikely that the room was actually painted in these intense shades, so the striking colours probably represent artistic licence.

Vincent added the following day: “I’ve tried to express the idea that the café is a place where you can ruin yourself, go mad, commit crimes”. The Café de la Gare, in Place Larmartine, was very close to the railway station and does indeed seem to have been a rough dive.

In May 1887, a year before Van Gogh’s arrival, a man named Jean-Pierre Fabre tried to commit suicide by cutting his throat in this café. One wonders whether hearing about this earlier incident might possibly have influenced the artist’s terrible later decision to sever an ear. Two young bullfighters in May 1889 had a violent quarrel in the Café de la Gare and ended up with serious injuries after a fight.

In 1908, The Night Café was sold by Theo’s widow Jo Bonger to the Moscow avant-garde collector Ivan Morosov, but it was confiscated by the Soviet government eleven years later, following the Russian Revolution. In 1933 the painting was sold abroad to raise funds for the regime and bought by American collector Stephen Clark, who bequeathed it to Yale University Art Gallery in 1961.

Van Gogh’s watercolour of The Night Café (September 1888)

Credit: Hahnloser/Jaeggli Foundation, Villa Flora, Winterthur (Photo: Reto Pedrini, Zurich)

Vincent also painted a watercolour after the oil original, to send to Theo. In the watercolour the contrast between the red and green is even stronger. There are also minor changes in the composition. For instance, the phallic composition of the billiard cue and two white balls has been delicately modified with the addition of an extra ball. There are fewer empty glasses on the tables, making the scene slightly more respectable.

Paul Gauguin’s The Night Café (November 1888)

Credit: Pushkin Museum, Moscow

When Paul Gauguin arrived in Arles, a month later, he made his own painting of the café interior. Gauguin portrayed the room from the left side, showing Marie Ginoux in a pensive mood, a glass of absinthe at hand. The café’s cat cowers beneath the billiard table. This painting also later ended up in the Morosov collection in Moscow.

Hotel Terminus, Place Lamartine, Arles (postcard), around 1920

Peter Senn’s photograph of a café in Arles, with the clock which is said to have come from the Café de la Gare/Hotel Terminus

In the early 1900s the Café de la Gare was upgraded to become the Hotel Terminus, with a café and a restaurant. The building would later be badly damaged by Allied bombing in 1944. It was rebuilt after the war, and the owner apparently saved the clock which had appeared in Van Gogh’s painting.

This clock is said to be the one which appears in a late 1940s image taken by the Swiss photographer Peter Senn on a visit to Arles, according to his note on the reverse. The café was finally demolished in the 1960s. Was the clock photographed by Senn the one in Van Gogh’s The Night Café—and where is it now?

Martin Bailey is the author of Van Gogh’s Finale: Auvers and the Artist’s Rise to Fame (Frances Lincoln, 2021, available in the UK and US ). He is a leading Van Gogh specialist and investigative reporter for The Art Newspaper. Bailey has curated Van Gogh exhibitions at the Barbican Art Gallery and Compton Verney/National Gallery of Scotland. He was a co-curator of Tate Britain’s The EY Exhibition: Van Gogh and Britain (27 March-11 August 2019).

Martin Bailey’s recent Van Gogh books

Bailey has written a number of other bestselling books, including The Sunflowers Are Mine: The Story of Van Gogh's Masterpiece (Frances Lincoln 2013, available in the UK and US), Studio of the South: Van Gogh in Provence(Frances Lincoln 2016, available in the UK and US), Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum (White Lion Publishing 2018, available in the UK and US) and Van Gogh’s Finale: Auvers and the Artist’s Rise to Fame (Frances Lincoln 2021, available in the UK and US). Bailey's Living with Vincent van Gogh: the Homes and Landscapes that Shaped the Artist (White Lion Publishing 2019, available in the UK and US) provides an overview of the artist’s life. The Illustrated Provence Letters of Van Gogh has been reissued (Batsford 2021, available in the UK and US).

To contact Martin Bailey, please email [email protected]. Please note that he does not undertake authentications.

Read more from Martin's Adventures with Van Gogh blog here.