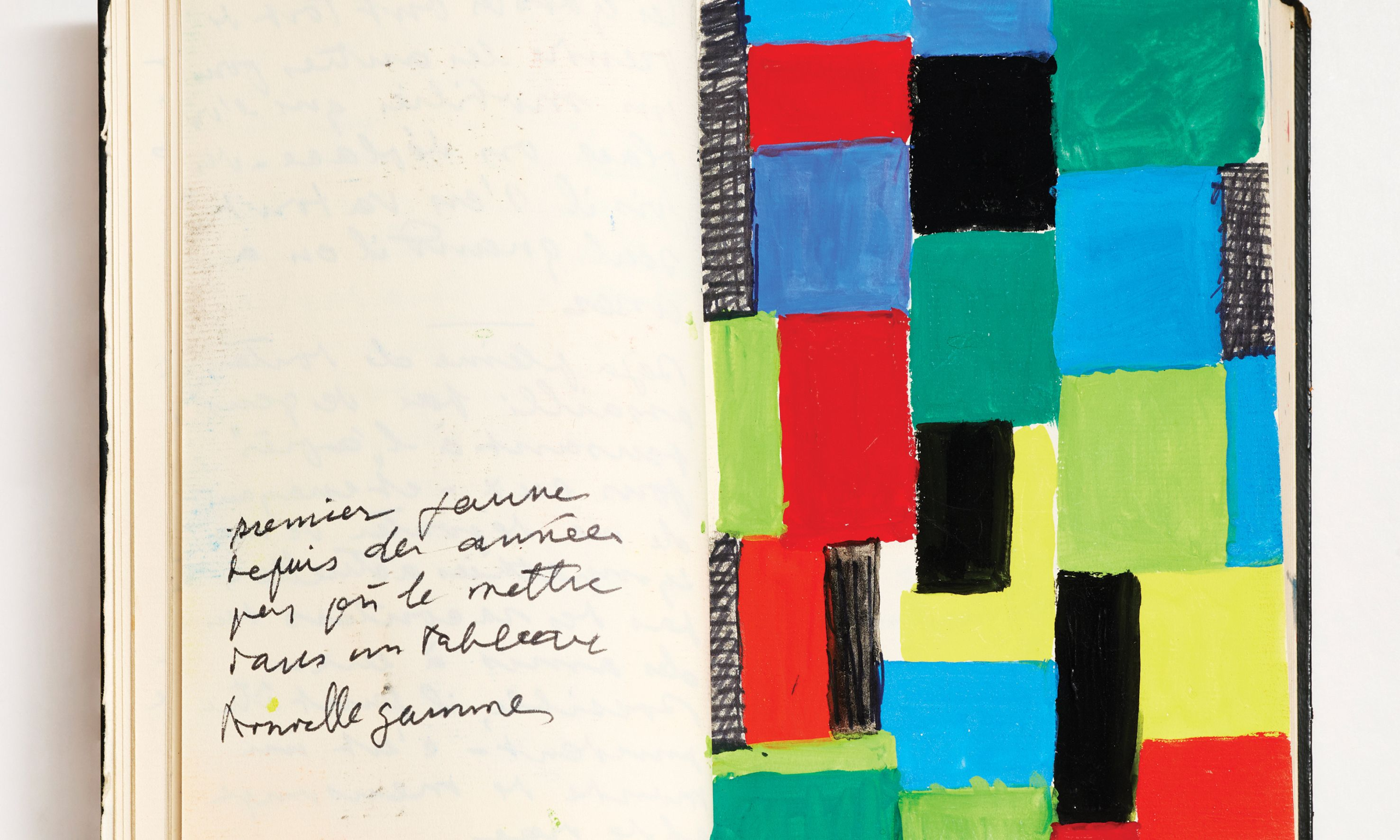

Sonia Delaunay’s personal journal and sketchbook of 1967, which has never been exhibited in public before now Photo: © Jean-Christophe Lett; © Pracusa

The avant-garde artist Sonia Delaunay (1885-1979) straddled the lines between fine art and decorative art as well as geographic borders. “While it is tempting to read [her] rich oeuvre through the prism of her origins, the artist herself, who was born in Odesa and raised in St Petersburg, clearly expressed during her lifetime that art transcends borders and nations,” says Waleria Dorogova, the co-curator of Sonia Delaunay: Living Art at the Bard Graduate Center in New York.

Russia’s 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine has highlighted Delaunay’s place in the historical context of both countries, but an important part of her development as an artist happened in Paris and elsewhere in Western Europe.

Delaunay’s wealthy relatives supported her art education in Karlsruhe in Germany and then Paris. She was associated with the School of Paris artists and her second marriage was to the French painter Robert Delaunay, with whom she developed the Orphism movement. Robert Delaunay, who died in 1941, wrote of his wife’s art that it “borrows nothing from the past and fully captures the spirit of our time”. Dorogova describes Delaunay’s 1968 recreation for the House of Dior of a dress she designed in the 1920s as “utterly of the moment” and her printed fabrics as fitting for “tomorrow’s runways”.

Sonia Delaunay's Broderie de feuillages (1909) Centre Pompidou; Musée national d’art issue; Paris; gift of Sonia and Charles Delaunay; 1964; AM 1142 OA. Digital Image; © CNAC/MNAM; Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource; NY. © Pracusa

The show will portray Delaunay as an innovator and entrepreneur and demonstrate how her striking avant-garde shapes and bold colours are a key part of the Modern canon. It will include nearly 200 of Delaunay’s objects made during a career spanning the 1910s to the 1970s, from paintings to fashion, furniture and even playing cards. Key loans will come from institutions such as the Centre Pompidou and Musée de la Mode de la Ville de Paris.

Many of the objects have not been exhibited before in the US, and others, such as her 1967 personal journal with gouache compositions, have never been seen before in public. The journal is on loan from Patrick Raynaud, an artist who is the last living assistant from her atelier. Raynaud has also contributed an essay that serves as the epilogue to the 540-page catalogue being released next month.

• Delaunay: Living Art, Bard Graduate Center, New York, 23 February-7 July