Gender Reporter, HuffPost

For someone seeking an abortion after their sixth week of pregnancy in Texas right now, the answer is simple: leave. Travel to a different state where you can access an abortion after six weeks, which, in Texas, is illegal under S.B. 8. It’s the only option left, even if it’s a logistical and financial nightmare.

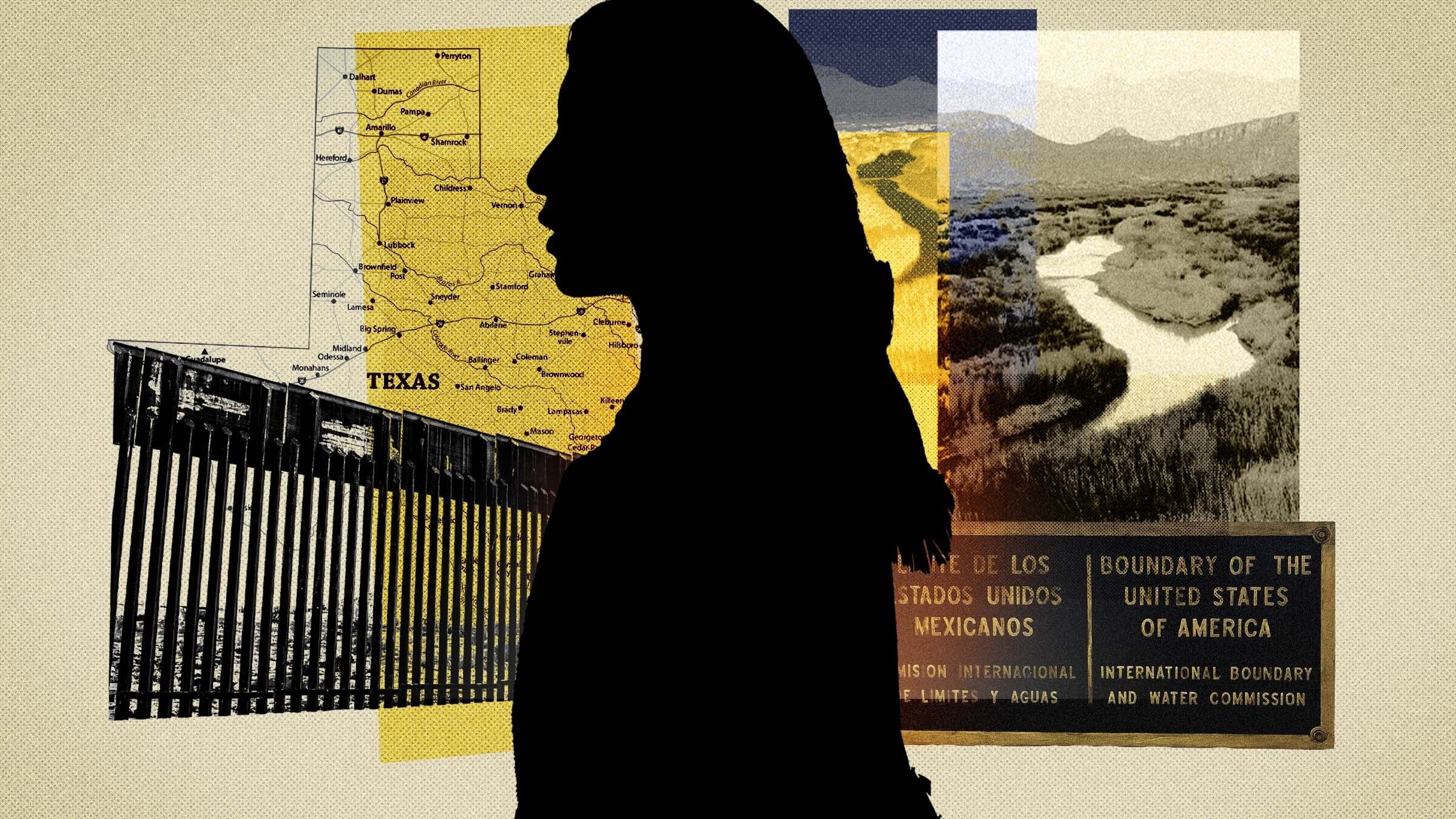

But what if you can’t travel out of state? What if traveling at all ― whether to go to the grocery store or the nearest clinic three hours away ― puts you at risk of being detained or deported? That’s the reality for undocumented people trying to access abortion care in Texas’ Rio Grande Valley.

Home to around 1.3 million people, the Rio Grande Valley is an “abortion clinic desert,” said Cathy Torres, the organizing manager at the Frontera Fund, a reproductive justice organization that provides financial and logistical support to undocumented people in the valley seeking abortions. The region, which includes four counties, only has one abortion clinic, Whole Woman’s Health in McAllen — the only abortion clinic from San Antonio, Texas, (four hours north of the valley) to Mexico City (eight hours south).

The valley sits at the southern tip of Texas, an area bordered by the Gulf Coast on the east and the Rio Grande River along the U.S./Mexico border on the west. Within 100 miles of the border, the valley also contains nearly 20 internal immigration checkpoints run by the Department of Homeland Security Customs and Border Patrol. If an undocumented person comes across one of these checkpoints and is asked to show documentation but doesn’t have it, they will be immediately detained.

“You can’t go to Mexico if you’re undocumented and you also can’t leave the valley because an hour north of you there’s another man-made border crossing,” Torres said. “You’re either forced into parenthood or risking deportation. Those are your two options if you’re undocumented and pregnant and don’t want to be.”

When Texas passed the country’s most extreme abortion restriction in September, advocates and providers scrambled to ensure people could still access the procedure out of state. Practical support groups worked around the clock to handle ride shares and flight costs; physicians and staff distributed information about these resources to patients; and state and national abortion funds raised money to help pay for procedures in other states. (Various courts have ruled to uphold or stay the law in recent weeks, further adding to the confusion of Texans seeking abortions.)

But organizers like Torres and Anna Rupani of Fund Texas Choice are worried that not enough attention is being paid to the barriers undocumented people are experiencing in the wake of S.B. 8.

“Undocumented folks are being left out of the conversation,” said Rupani.

Intersecting identities highlight how abortion restrictions like S.B. 8 will disproportionately impact the most marginalized populations: immigrants, people of color, poor people, and people in rural or underserved geographical locations. S.B. 8 not only bans abortions after six weeks, a time in which most people don’t know they’re pregnant, but it also financially incentivizes private citizens to seek out and sue anyone who “aids or abets” Texans trying to get an abortion. If someone successfully sues, they could receive a bounty of at least $10,000 and have all of their legal fees paid for by the opposing side.

Border Patrol checkpoints and abortion clinic deserts are the most glaring barriers for undocumented Texans in the wake of S.B. 8, but they’re not the only obstacles. Abortion care costs, lack of access to resources in Spanish and other languages, as well as the continued militarization of the border are constant deterrents for undocumented folks seeking abortion care in the Rio Grande Valley.

The cost of an abortion in the Valley is very high — ranging from $800 to $1,500, depending on gestation — because the few clinics left in or near the area are privately run. In comparison, the average cost of an abortion in other areas of Texas, like Houston, is around $600.

And although coverage like Medicaid is available (albeit to a limited degree) for undocumented immigrants, it doesn’t matter: The Hyde Amendment, first passed in 1976, restricts federal health insurance from covering abortion procedures. Rosie Jimenez, a native of the Rio Grande Valley, was the first known victim of the Hyde Amendment after she attempted to get an abortion in 1977 but couldn’t afford the procedure because Medicaid no longer covered it. Jimenez later died after going to an unlicensed midwife who offered to do the procedure for less money. (Texas has its own version of the Hyde Amendment, S.B. 214, which passed in 2017.)

“It’s confusing enough in English. Expecting other people who speak different languages to just understand this when we are still learning about it, that’s an issue.”

Language is another big roadblock, especially for undocumented people who are attempting to navigate really complex laws — like S.B. 8 — written in English.

“Other than from advocates like ourselves, where have you seen information about S.B. 8 talked about in other languages?” Torres asked. “It’s confusing enough in English. Expecting other people who speak different languages to just understand this when we are still learning about it, that’s an issue.”

Sharon, an undocumented woman currently living in Texas who asked to be identified only by her first name to protect her identity, had an abortion in 2016 and was forced to travel to New Mexico because she was unable to get abortion care in Texas, which had a 20-week ban in place at the time. Although she was on a student visa then, Sharon said she was still worried about traveling. Abortion funds helped her raise $9,000 in three days so she could fly out of state and get an abortion later in her pregnancy.

“It was really scary because at that time I was on standby on my student visa because I didn’t study that semester. They said if I didn’t study my visa was going to be out of status. So I was like, what am I going to do? What if I fly and something happens? I was really scared,” she told HuffPost.

Sharon didn’t have issues with a language barrier since she studied English in her home country, but she did see how hard it would have been if she couldn’t speak English. When she was at her appointment at the New Mexico clinic, Sharon had to translate for a woman who didn’t speak English. At one point, the woman called Sharon from her hotel room because she was in such severe pain after the procedure and needed Sharon to speak to clinic staff for her.

“If I didn’t speak English, I know for sure it would’ve been impossible to get an abortion,” Sharon said.

Nancy Cárdenas Peña, the state director for the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Justice in Texas, also pointed out how the militarization of the border and immigration policy impact undocumented residents seeking abortions. S.B. 4, which passed in 2017 and allows state police officers to act as immigration agents, has only further marginalized undocumented folks.

“There’s always been a steady increase and funding of military and police in the valley to quell a so-called border crisis that doesn’t seem to exist for people in the valley but for some reason it exists for the governor,” Cárdenas Peña said.

When looking ahead at the possibility of the Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade ― the landmark decision that protects a person’s right to an abortion ― Torres was realistic about life for many in Texas: “We’ve already been navigating a post-Roe world,” she said. “Being from a community that is often left out of the conversation and faces more disparities than other regions, abortion is not accessible whatsoever here, especially if you are undocumented.”

And if Roe is overturned, it will only get worse. “I’m a human being. I’m really scared about Roe v. Wade being overturned,” she admitted. “You have so many people who say, ‘That’s so extreme, it would never happen.’ But everyone said S.B. 8 was extreme and wouldn’t happen and look at where we are now.”

Gender Reporter, HuffPost