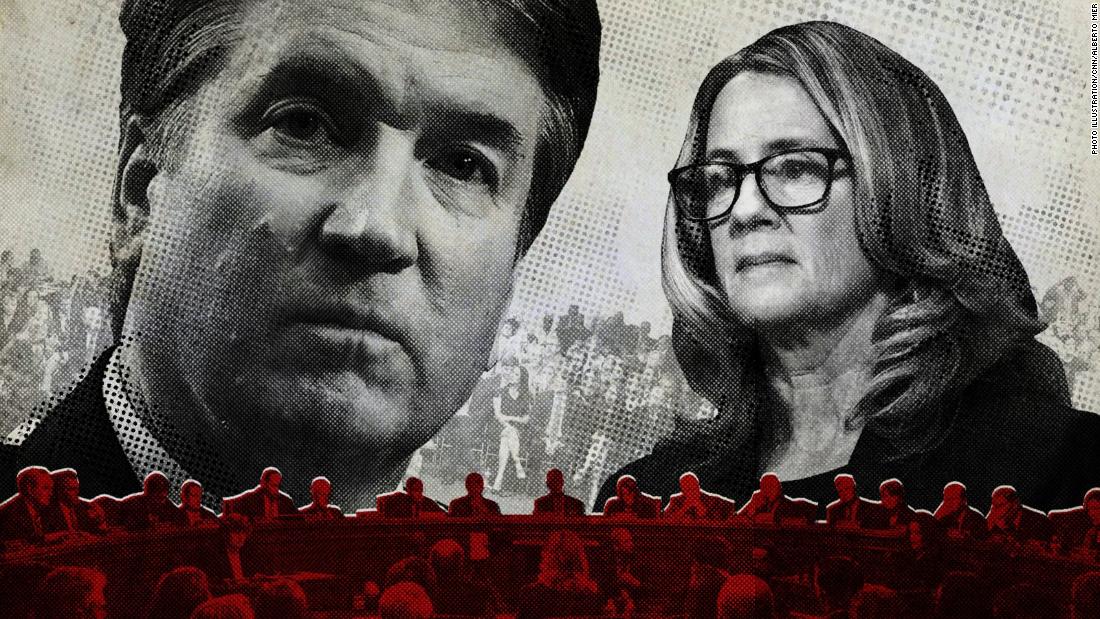

Defense attorney Page Pate said Blasey Ford “nailed it,” which was why it was such a bad look for the committee’s Republicans to have their chosen prosecutor, Rachel Mitchell, suddenly stop her questioning of the sobbing nominee. They dropped her “like a hot potato when it came time to really confront Judge Kavanaugh about these allegations.”

Kavanaugh’s repeated crying as he defended himself before senators,

wrote Michael D’Antonio, showed the “wider latitude” for emoting that men in politics have today (he noted that a woman acting the same way would have been called “hysterical.”)

Kavanaugh had a right to despair, observed Scott Jennings, and “deserves credit for fighting like hell to defend his honor, his reputation and the family name carried by his wife and daughters.”

His emotional turn was a far cry from the placid jurist the nation saw earlier in the week in a Fox interview—with wife Emily Estes Kavanaugh at his side—a preemptive strategy all about the optics, said

author Rebecca Wanzo. The well-worn “good wife” trope sends a message (as it did for Bill Clinton and Clarence Thomas): “if the wife and family are the injured parties, the woman who has brought forth the charge is understood as victimizing a woman and children too.” (A viral photo of women at the hearings, on the other hand, delivered on a very different set of optics.) For many women it was simply a harrowing day.

Daniel Campoamor wrote that Kavanaugh’s “overt anger, his unapologetic willingness to yell and, at times, cut off sitting senators,” triggered a “physical response I was powerless to control.” After she dropped her daughter at school, Tess Taylor pulled over to cry as she listened to Blasey Ford’s testimony

and reflected on the hard work still ahead for women: “I cried because I am angry. I cried because I want a world where my daughter trusts her voice and her stories will be listened to.” And

Karine Jean-Pierre asked: “What is our duty to a system of civics that no longer serves our people, but severs them from justice”?

Are you kidding?

When Bill Cosby was sentenced to prison Tuesday after years of sexual assault allegations, some of his defenders said he was a black man who was set up. Are you kidding?

wrote Kyra Kiles in the Grio. Instead of martyring a predator they should use their energy to help, not silence, victims for “a stranger they ‘know’ only from behind the warm glow of a TV screen.”

The Independent’s

Kuba Shand-Baptiste wrote that a reluctant Hollywood Chamber of Commerce needs to scrub Cosby’s star from the “Walk of Fame”: “To suggest that his legacy, and not the people he hurt through it, deserves special protection beggars belief.”

UNGA-lievable

Was laughing at Trump’s UN General Assembly comment really such a good idea? World leaders lost it when President Trump proclaimed that “my administration has accomplished more than almost any administration in the history of our country” —

and Nic Robertson has a warning for delegates who joined in: “Hope you don’t get found out. President Trump likes respect. He won’t forget. And he may get the last laugh.”

In any case, his speech was aimed squarely at voters back home,

wrote David Andelman. It was a hard sell for “America first” and a hard slam at Iran. The world should worry, Andelman wrote: “Trump’s defiant messaging — given Iran’s steadfast adherence to a nuclear deal that the United States wants desperately to kill — is powerful evidence” that he is hurtling the globe toward nuclear proliferation.

While dignitaries clogged New York’s streets with limousines and crowded into receptions around town,

Edward Miliband, the former British Labour Party leader and now president of the International Rescue Committee, implored the UN to end the suffering in Yemen. The country’s “morass is complex, but not insoluble,” he wrote. It’s “a man-made crisis [with] a man-made solution,” beginning with an immediate ceasefire.

——————————

‘Censoring’ Bourdain

The late, great Anthony Bourdain was brilliant and fearless. Here was a writer and storyteller who didn’t give a ****. But what you might not know is that he didn’t get a **** either, or a *****, or even a ****. Not if

Marianna Spicer Joslyn could help it. She is executive director of News Standards and Practices at CNN, and was in charge of making Bourdain’s freewheeling show clean enough for cable.

“I was Anthony Bourdain’s ‘censor,'” she writes. It was her job to kill off the bad words, plus the fat jokes, the off-color descriptions and the sex talk. But without killing what made Bourdain unique and interesting. “Of course, Tony was very, very funny. We had to seek a middle ground in many areas… Like his viewers, I fell in love with Tony.”

— What is “period poverty?”

Amika George, an 18-year old student in London, explains.

Thousands of UK girls have to skip school when they menstruate because they can’t afford tampons or pads. George started the #FreePeriods program, eventually getting the British government to allocate money for it, and becoming a hero to many girls. She was in New York last week to pick up a Global Goals Campaign award. “The fight is far from over,” for girls around the globe,

she writes. Access to menstrual products must be “treated as a universal human right, not a privilege.”

— The question is: What would Olivia Benson do? With its 20th season premiere, “Law and Order: Special Victims Unit” made TV history this week

. And made Melissa Blake wonder if its complicated protagonist Olivia Benson (Mariska Hargitay) is the female role model we need in 2018: “a TV show like ‘SVU’ has never been more relevant — or more needed,” she writes.

Next chapter?

As we head into a new week of Kavanaugh, expect the pending FBI investigation to hang heavy in the air.

James Gagliano says leave it to “Carla F. Bad.”

Who’s she? “Well, ‘she’ is the readily memorized acronym that reminds investigators of just what to investigate when looking into someone’s background. It is an enduring checklist that the FBI utilizes to assess honesty and trustworthiness in someone holding, or seeking to hold, a position of trust in our republic,” he writes.

“The acronym represents character, associates, reputation, loyalty, ability, finances, bias, alcohol and drugs. It was presumably employed during Judge Kavanaugh’s multiple background investigations during his tenure in the Bush 43 White House, and when he was appointed a federal appeals judge in 2006.”

Let’s hear what Carla says.