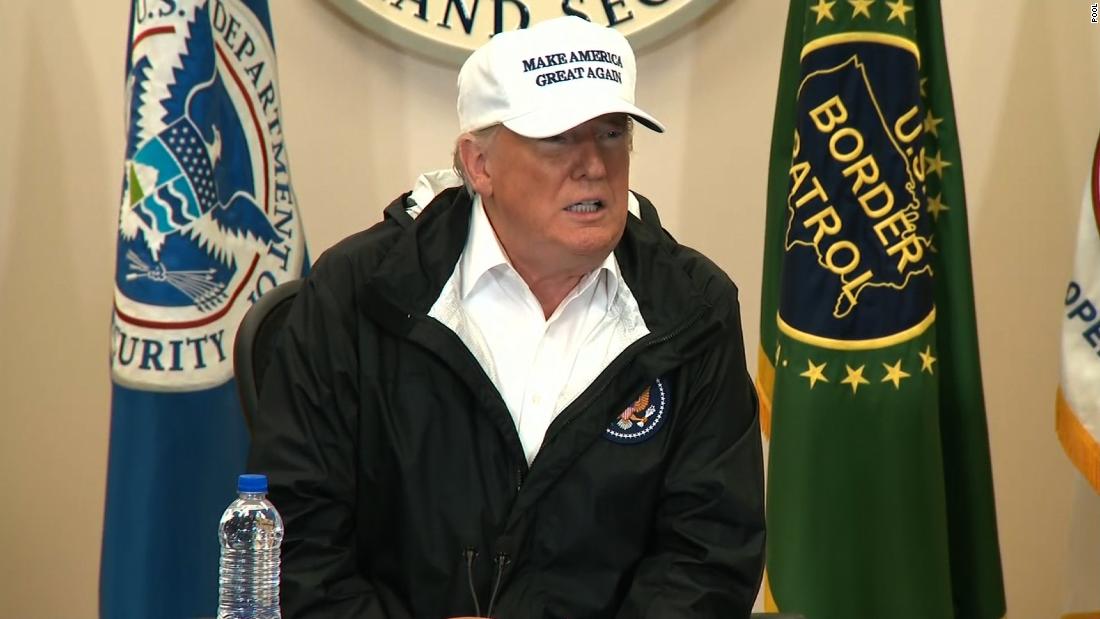

While Trump speaks at the El Paso County Coliseum — just steps away from the US-Mexico border — the city will have to confront the reality that our community is not united in protecting the immigrant community and its contributions to our city.

In short, the rally has forced El Pasoans to answer two major questions: What do we believe in? And who do we want to support?

But I did not need police records to tell me my city was safe before border fencing was installed. I’ve lived on the border for most of my life.

During my high school years, from 2003 to 2007, my friends and I joined our older classmates in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico to drink cheap cocktails, eat hot dogs on the sidewalk, and still make it home by our 11 p.m. curfew — the way our parents and their parents did before us. This continued through 2008, until the drug violence in Juarez escalated. And even then, the escalation later

positively impacted El Paso’s economy, as families and businesses moved across the border.

In college, from 2007 to 2011, my girlfriends and I would regularly go out in entertainment districts in downtown El Paso. I never felt threatened or in any kind of danger. The worst run-ins were with drunk men at bars.

But misrepresenting the safety of El Paso before the building of the fence isn’t Trump’s only mistake.

In 2007, a year after former President George W. Bush signed the Secure Fence Act, giving the greenlight to build the fence in El Paso, as well as in other towns along the border, the crime rate in El Paso began to increase. From 2007 to 2010, while murders did not increase, overall crime

increased by 5.5%, according to the FBI. Those numbers have since decreased again.

Still, El Paso remained one of the safest cities to live in. In 2018, US News and World Report

ranked El Paso as No. 11 for “best places to retire” because of the city’s safety and economy. In the same year, author Gary Shteyngart took a cross-country road trip and decided, on PBS’s NewsHour segment “In My Humble Opinion,” that El Pasoans are

the happiest people in the country. Hardly surprising to me, since El Paso is a place that welcomes outsiders and takes pride in hospitality.

Even with an increase in crime post fencing, the first time I felt unsafe in El Paso was November 2016, after Trump was elected. I feared for my reproductive rights, healthcare and overall safety. More specifically, I feared that my work as a journalist might place me in unsafe situations because of the hostility MAGA rally attendees often display toward the press — and that El Paso would become the site of tragedy if the lives of immigrants here were suddenly disrupted.

In 2017, Trump

threatened a “border-adjustment tax” that would be imposed on goods coming in from Mexico. The tax would be placed on goods based on the location of their final consumption — rather than the site of production. In other words, El Pasoans would end up paying more for these products. Critics said that the move could result in a trade war, starting in El Paso, and Trump and GOP leaders opted to drop it. Instead, Trump has negotiated a new trade deal with Mexico and Canada, a revamped version of NAFTA.

Yet again, Trump’s proposed border wall challenges the way the city has successfully operated for years, and many fear new border security measures are being decided without understanding the unique needs and demographics of the city. For example, many students who attend the University of Texas at El Paso are Mexican nationals

who legally cross over every day to attend classes, and the city

flourishes from bi-national commerce.

Even with all these facts in hand, El Pasoans remain divided. Liberals in El Paso are outraged by the inaccurate statements that Trump has made on the public stage. “It was heartbreaking for me to sit as I listened to someone demean and belittle all the greatness of my community,” Senaida Nevar, Democratic Congresswoman Veronica Escobar’s guest at the State of the Union, told me.

“Everything that El Paso is today is a direct result of the values and principles that every resident, be it an immigrant or citizen, has worked so hard to preserve,” she added.

And Beto O’Rourke is hosting his own rally, not far from Trump’s, where he is scheduled to speak about why a wall is unnecessary, reiterating many facts that seem to have been forgotten.

At the same time, those who support the President’s stance

are incensed that their views are not being respected by those across the aisle. They believe they are protecting the country from rampant violence and crime, even if the statistics do not entirely support their beliefs.

Perhaps they are also benefiting from taking a hardline stance. According to Vincent Perez, El Paso County Commissioner, El Paso generated

more than $22 million in revenue in 2017 for detaining federal inmates, the majority incarcerated for immigration-related crimes.

For years, El Paso has

maintained a contract with the government to house federal inmates. “We’re required to provide at least 500 beds or at least make available to the federal government,” Perez told me. “But what we’re seeing with this rush of migrants, that number is sometimes higher than 900.

“So, it’s no coincidence that the largest share of the population of these inmates that we house at the county jail are here on immigration-related charges.”

Regardless of the outcome of today’s rallies, El Pasoans should not rush to build walls. Instead, we should focus on the facts and start a dialogue in which both sides meet in the middle.