[ad_1]

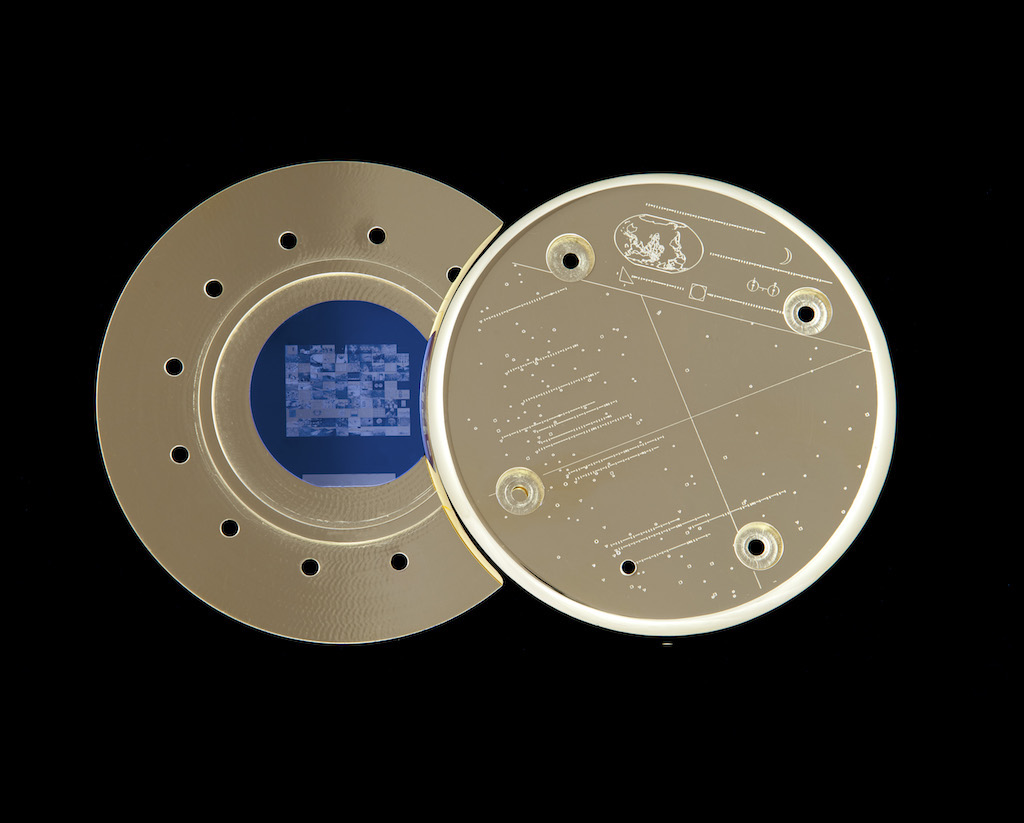

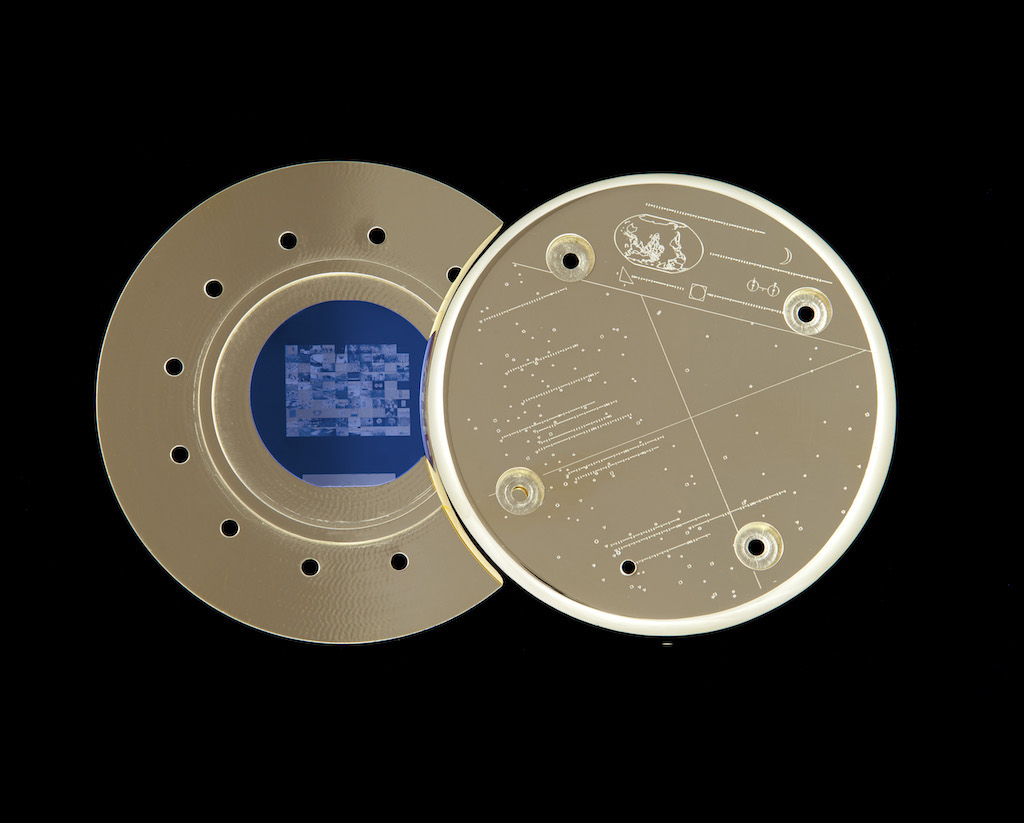

Trevor Paglen, The Last Pictures and the Gold Artifact, 2013, etched gold plated disk and HD video.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND METRO PICTURES

Trevor Paglen has been making some of the most influential photographs and sculptures about surveillance technology of our era, such that he won a MacArthur “genius” award last year. With surveys of Paglen’s work currently on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., and the Museo Tamayo in Mexico City, we are republishing a report on the artist’s project The Last Pictures, for which Paglen crafted a disc that was micro-etched with 100 photographs and beamed it into space via a satellite. Originally written for the November 2012 issue of ARTnews, Robin Cembalest’s report on the project features Paglen’s musings on the problems of conceptual art and the process behind making the work, which was commissioned by the organization Creative Time. The piece follows in full below. —Alex Greenberger

“Alien Nation”

By Robin Cembalest

November 2012

Maybe at some point in the future an alien will stumble on a piece of space junk from a galaxy far, far away. The object, perhaps still ensconced in its gold-plated aluminum cover, is a silicon disc embedded with curious engravings. Like the French teens who discovered the cave paintings at Lascaux, perhaps the alien will perceive its find as something very special and will scrutinize its markings for what they say about the remote culture that made it.

Maybe not.

Even Trevor Paglen, the artist who spent five years picking 100 images to fill this space-bound time capsule, devising a return address that unimaginable life forms might understand, and creating a package that could survive billions of years, admits that the possibility of extraterrestrials finding—much less interpreting—his silicon artifact is not so good.

Nevertheless, the staff of the public-art nonprofit Creative Time, along with the MIT students, scholars, scientists, and satellite-corporation executives who helped Paglen along the way, honored the process. That’s how the artist’s disc ended up attached to the EchoStar XVI, a communications satellite serving Dish Network subscribers that is scheduled to launch from Kazakhstan this fall.

Glimpses of America, American National Exhibition, Moscow World’s Fair, 1959. This photograph is one of 100 that was featured in Paglen’s project The Last Pictures.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND METRO PICTURES

If the calculations of Paglen’s team are correct, his little archive will survive longer than people or Earth, making it the farthest-traveling, longest-lasting artwork in the history of history. This represents one giant leap for Creative Time, whose previous forays into space include hiring crop dusters to skywrite Vik Muniz’s cloud drawings above Manhattan and staging Tom Sachs’s earthbound voyage to Mars in the Park Avenue Armory.

The organization wanted the human audience to see The Last Pictures too, so it gathered the images in a book. Recently, the volume (copublished with the University of California Press) was launched in Manhattan, beneath the stars, at a public conversation between Paglen and Werner Herzog. The matchup seemed obvious, since the curmudgeonly film director shares so many obsessions—cave art, frontiers, code cracking— with the artist, who describes himself as a “cultural geographer.” Still, I was a little nervous for Paglen, having recently seen Herzog at the Whitney, where (at an event staged to coincide with the Biennial, which he was part of) he had denounced conceptual art and insisted that it would never stand the test of time. And here he was, discussing a conceptual art project that’s supposed to last longer than we do.

Predictably, Herzog did not like the “Star Trek mentality” that suggests that aliens as we imagine them actually exist. But he played along with the concept, endorsing the presence of cats in Paglen’s mix and warning against using art to communicate with beings that lack sight as we know it. “How,” he queried, only partly rhetorically, “will aliens see your Paul Klee?”

But then, we can’t see the Klee either. It’s the label affixed to the back of Klee’s 1920 watercolor Angelus Novus that begins Paglen’s 100 images, which appear without any text. The captions, such as they are, are in an appendix. There, we learn that this picture, before it was inherited by the Jewish mystical philosopher Gershom Scholem, was owned by Walter Benjamin, who discussed it in his Theses on the Philosophy of History, written shortly before he died while fleeing the Nazis in 1940. Benjamin described Klee’s angel as looking back, be- holding a great catastrophe.

Greek and Armenian Orphan Refugees Experience the Sea for the First Time, Marathon, Greece. This photograph is one of 100 that was featured in Paglen’s project The Last Pictures.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND METRO PICTURES

Clearly, we’re not in Carl Sagan territory anymore. The optimistic we-are-the-world quality of the Voyager Golden Record, launched 35 years ago, is nowhere present in The Last Pictures. The book is a perverse, obscure, awe-inspiring, heartbreaking, brain-twisting selection of images, culled from libraries, databases, and archives, that appear in a progression Paglen describes as a silent film or a poem. The sequence of black-and-white reproductions has the dreamlike quality of a Chris Marker movie, where the documentary photos evoke science fiction, and the science fiction—like the set of Escape from the Planet of the Apes—seems real.

The presumptive great achievements of humanity—space travel, modern art—come off as quaint and obsolete. Ai Weiwei shows up, giving the finger to the Eiffel Tower. For every attempt at communication, there is a misstep, like the Tower of Babel (rendered by Pieter Bruegel the Elder) or Esperanto’s also-ran, Volapük. Global warming, industrial pollution, and man’s inhumanity to man are expressed in deviously cheerful images of prisoners of war and children deformed by Agent Orange. Great sea creatures, like the whale and the shark, are captive in aquariums. Others are farmed or cloned or genetically altered. The fruit fly has legs where its antennae should be. Even cats are pressed into service in a sadistic piano.

If Earth hasn’t been entirely destroyed by the time aliens find this, these images could make them want to finish the job.

As depressing as all this is, it’s uplifting to think of all the people who came together to get Paglen’s disc ready for liftoff: anthropologists and philosophers; cognitive scientists and aerospace engineers; experts in quantum nanostructures, materials science, message encoding, and more.

As several of these specialists make clear in the book, none had illusions about communicating with aliens. But they threw themselves into this quixotic art project anyway.

This inner beauty of the making of The Last Pictures is the real reason it works as public art. No matter what happens in outer space, Paglen has been colonizing inner space all along.

A version of this story originally appeared in the November 2012 issue of ARTnews on page 46.

[ad_2]

Source link