[ad_1]

This story is a collaboration between HuffPost and The Lens.

This year, the kids learned papier mâché. Their creations line the walls of the art and electives room. In the adjacent hallway, bright blue plywood covers the spots where students punched or kicked holes in the drywall as they passed between classes.

This is the middle school campus for the New Orleans Center for Resilience, a nonprofit K–8 school with two locations in the city. The 27 kids enrolled in the center’s program have some of the most extreme behavior needs in the city, often stemming from trauma or mental illness. A typical student may have exhibited verbal and physical aggression, caused property damage or refused to do classwork. It’s a place for kids who have almost nowhere else to turn — when they’ve been asked or told to leave their previous schools.

“A lot of the kids who are referred here have experienced significant complex trauma,” said Liz Marcell Williams, the center’s director. “Whether they themselves have been victims of trauma or they’re exposed to violence in the home or in the community or have experienced significant loss of a loved one due to long-term incarceration or death.”

New Orleans, a high-poverty, high-crime city, has particularly pressing needs when it comes to trauma and behavioral health.

A survey of about 1,200 New Orleans kids ages 10 to 16, released in 2015, found that nearly 40 percent had witnessed domestic violence, a shooting, a stabbing or a beating. About 18 percent reported witnessing a murder. And more than half said that someone close to them had been murdered.

The survey found that children in New Orleans displayed symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder at more than three times the national average.

The center, which was known as the Therapeutic Day Program until Dec. 1, is a rare lifeline to the few who get in. When it opened in 2015, it was the first school of its kind in New Orleans, offering a blend of traditional classes like math and English, as well as therapy and counseling. In a city where student mental health resources remain scant, there are few places like it today.

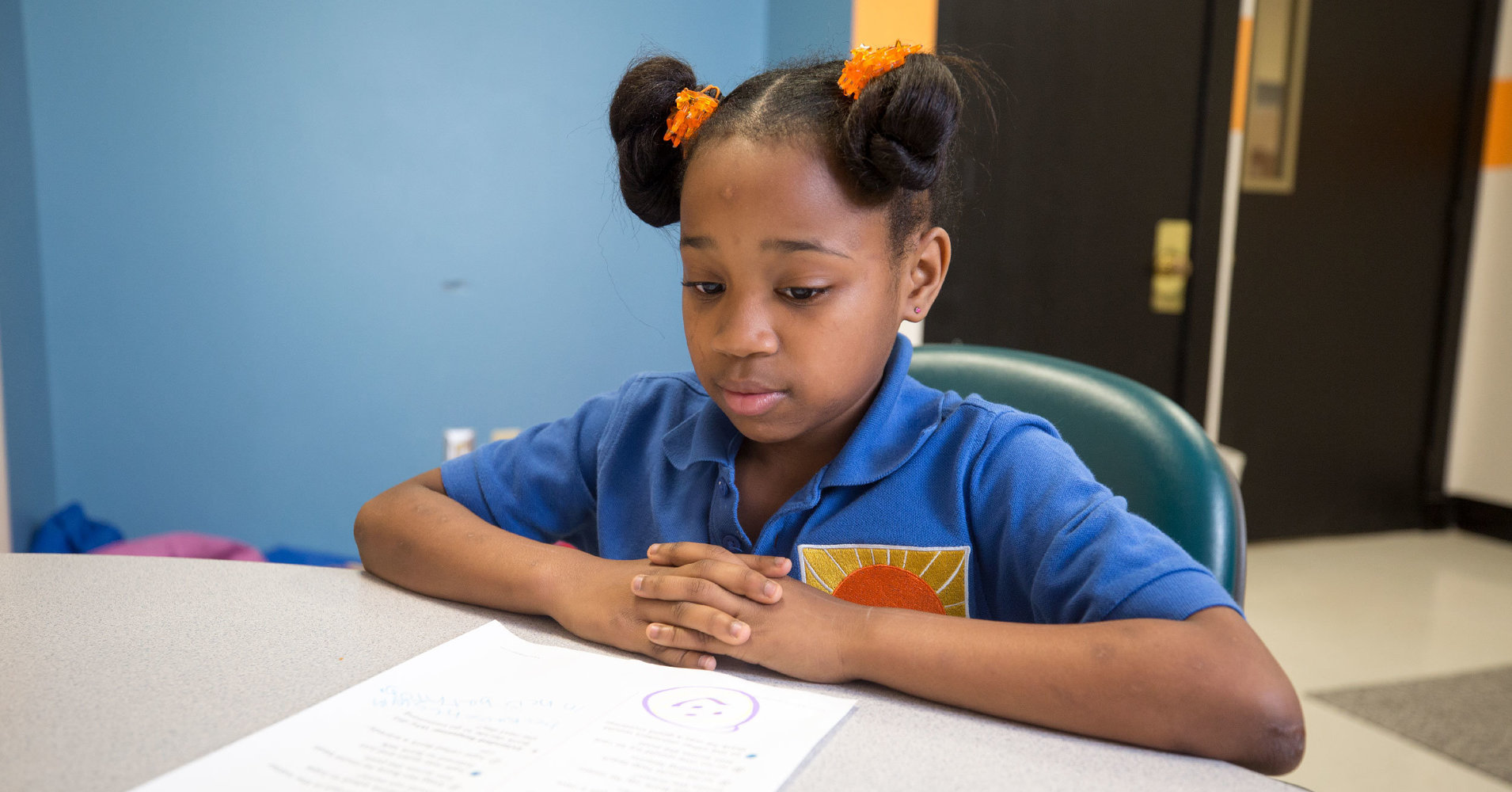

L. Kasimu Harris for HuffPost

Kids who arrive at the center are usually three grade levels behind in math and reading, said Williams, who has a background in special education and designed the school’s curriculum. Her goal is to get kids back into the mainstream school system. Students attend the center for an average of 15 months.

Nine-year-old Misty Johnson, who has ADHD and bipolar disorder, has been in the program for two years. Her mom, Dawn Johnson, said Misty is almost ready to return to a charter elementary school.

Johnson admitted that she was worried when she first visited the center. “The other kids were just like Misty,” she said, adding that she thought it might be overwhelming for her daughter.

Over time, however, she saw improvements in Misty’s behavior and academics. Many of the classes here are tiny; some have just two students. Misty was getting lots of one-on-one attention. The school called Johnson regularly to give updates.

This year the center started assigning students a home base room, where they begin their day with breakfast. The home base is meant to be a safe room, and students may return there during the day if they need to opt out of a class or activity. In a typical school, students don’t usually have the option to walk out of class if they’re feeling overwhelmed.

L. Kasimu Harris for HuffPost

“We’re always thinking about how do we minimize power struggles,” Williams said. The home base room really helped them with that, she added. From August to November last year, the center had 235 behavioral incidents requiring an adult crisis response, she said. This year in the same time frame, there were 77. The home base rooms were partly responsible for that, she said.

Despite the high rate of turnover at the center, most kids who apply for a spot at the tiny school never get in.

Only 45 kids have attended since the school opened. Erin LaFleur wanted her 14-year-old son, Brady, to be one of them. He has bipolar disorder, autism and Down syndrome and spent time in a state-run facility that was several hours away by car. She fought long and hard to navigate the New Orleans public school system for him, and she said she thought the center’s day program would be a perfect fit.

But he couldn’t get in.

He lacked the verbal communication and social skills necessary for the program, a rejection letter stated.

“It would benefit children with intellectual disabilities who have behavior disorders if [the center] accepted them,” LaFleur said.

Williams said the program is working to expand. She said that she wants it to enroll high school students and that she would also like to run a trauma-informed early childhood program.

[ad_2]

Source link