[ad_1]

Touria El Glaoui and Mariane Ibrahim at Lucien in New York City.

©KATHERINE MCMAHON

Touria El Glaoui is the Moroccan-born, London-based director of the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair, which was founded in 2013. After two editions in London, the fair expanded to New York in 2015 and later, in spring 2018, to Marrakech, Morocco—the first location on the continent for a fair devoted solely to art from Africa. The most recent edition, this past May, at the Pioneer Works art center in Brooklyn, featured 21 galleries from 11 countries.

Mariane Ibrahim, who was born in Nouméa, New Caledonia, and raised in Somalia and France, founded Mariane Ibrahim Gallery in Seattle, Washington, in 2012. She works with a roster of primarily African artists while maintaining a presence at international art fairs. In 2017 she won the Presents Booth Prize for a presentation of work by the German-Ghanaian artist Zohra Opoku at the Armory Show in New York. Her gallery in Seattle is currently showing “Common Place,” a two-artist exhibition featuring the Brazilian painter Sergio Lucena and South African multidisciplinarian Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi. She also collaborated on an exhibition of recent African textile work on view through August 3 at Sean Kelly gallery in New York.

ARTnews convened with El Glaoui and Ibrahim at Lucien, a French bistro with a storied international élan in New York’s East Village. For El Glaoui, the steak frites; for Ibrahim, steak tartare. — Andy Battaglia

ARTnews: By certain metrics, the ascent of contemporary African art has been swift. To what would you attribute that?

Touria El Glaoui: Awareness comes from collective movement—the work of a lot of people. Being in the art market, when we talk about prices and value, we might shed light on certain things that become more visible, but we all benefit from global interest now. It’s actually a lot of people, a collective number of galleries starting their businesses in Africa in the past five or six years, but also the auction houses and art fairs. You have a lot of incredible initiatives on the continent, a lot of publications being written, and also museum visibility—the fact that they give confirmation to what we do by doing shows or acquiring pieces, making contemporary African artists part of their collection, and giving more visibility to artists from the African diaspora.

Mariane Ibrahim: You have the impression that it’s fast because it’s basically like a room that is slowly filling up with water until a point where the door gets opened and you see it all let out. Contemporary African art has been a very confidential circle. Collectors of it existed, but they were not involved in institutional programs and their eyes were scattered in different categories. There has been a strong influence from the South African galleries, curators, and artists, but South Africa is South Africa—it has its own reality, its own codes, its own history.

ARTnews: Has it felt like a recent rush to you?

Ibrahim: It often gets compared to China as the next big thing. The contemporary art scene in Europe and America is saturated, so they’re looking for new blood. The connection to technology has allowed access to artists who don’t necessarily have representation, and so have art fairs. When Touria created 1-54, it injected energy to give visibility to what was invisible—my gallery, and the artists I work with, included. It has been laborious, and there has been work that was done before, but now it’s on a good trajectory.

The 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair at Pioneer Works in Brooklyn.

COURTESY THE 1-54 CONTEMPORARY AFRICAN ART FAIR

ARTnews: What was the impetus for starting 1-54?

El Glaoui: Timing is everything. I had the chance to travel a lot to the continent and, living in London, I was surprised that what I was seeing was not crossing over geographically. I saw a lot of things that I wanted people to see. It was also a time when, in London and the United States, people I didn’t know yet were thinking about the same thing and starting their own galleries. Tate announced an acquisitions committee focused on Africa and also did two exhibitions of African contemporary artists, which gave certain confirmation to the importance of having African artists in the discourse of their collection. In 2013 a lot of us were looking to support a scene that we believed in but people didn’t have access to. A lot of collectors and institutions, even if they have contemporary African galleries or departments, don’t have the budget to go to Africa to discover artists. And a lot of people still do not associate Africa with contemporary art. I have plenty of people visit the fairs not having conceived they were possible for contemporary African art.

ARTnews: Mariane, how did you first launch your gallery?

Ibrahim: It started in 2012 in Seattle, but it really began before. I was living in Paris and couldn’t understand, with the relationship that France has with Africa, why they hadn’t been able to create exhibitions and spaces to promote the contemporary art scene of Africa. There were a lot of factors for that, but it is true that most of the institutions have an insufficient vision of Africa where there is always a connection between the artist and his ethnic background, the artist and his tribal system. That’s how they were looking at artists then, and there’s still room for improvement, because you have curators—the same curators who are dealing with aspects of Africa that are very traditional—who are not embracing that, today, African artists are dealing with gender issues, climate issues, and social issues as much as artists based in New York. There is this kind of fetishization of art coming from Africa, where it’s constantly “this is the country, this is the strife . . . .” The idea of Africa to me personally, as an African, it’s like the title of 1-54—one continent, 54 countries—which says everything. But Africa is a concept because there’s so much diversity. I am from the continent, and this other person is from the continent, but we have different realities and I don’t understand why we are put in the same box. People say, “This is art from this region, this is art from this other region”—to me, that’s totally obsolete. That’s a source of malaise and frustration, and the gallery came from that malaise.

ARTnews: How much of your business comes from Seattle versus elsewhere

Ibrahim: Seattle is a provincial city. It’s very small. There are collectors but not much interest for international art. I have been supported by institutions there that have acquired work and have done exhibitions, but it’s not one of their focuses. That’s one of the reasons I exported myself and started to do art fairs. Actually, the collectors in Seattle pushed me to get out, and then I kept going and going, and the gallery grew that way.

ARTnews: Where is the market strongest in your experience right now?

Ibrahim: It stays in Europe, but America is really waking up. The great advantage of America is the institutions are less fearful in welcoming artists. Museums, university museums, art centers—they’re taking risks and are engaging with artists. But there is something else we experience year by year: there’s a growing number of African collectors based in Africa. We need to nurture those. The fact that they are coming to the table is making the scene more exciting, not only for the artists but for the dealers as well.

ARTnews: Where is the market most active in Africa?

El Glaoui: It’s very spread out. There’s definitely a correlation between how well the economy of a country is doing and how its art scene grows. We talked about South Africa leading the way, but South Africa has been in the leadership position in terms of development for a long while. North Africa, between Tunisia and Morocco, also has a strong base. It’s been stable for a while, we have seen a bourgeoisie develop, and wealthy people have appeared in the past 20 or 25 years in the corporate world. And then Nigeria, before the oil crisis, had a good few years with high oil pricing that created a boom in the art world there, enough to create galleries, collectors, and a local art fair as well. Then there have been scattered bits everywhere, in Ivory Coast, Kenya . . .

View of Pascale Marthine Tayou’s Summer Surprise, 2017, in the courtyard outside of Somerset House, at 1-54 London, 2017.

©KATRINA SORRENTINO

ARTnews: How does the United States compare in terms of interest?

Ibrahim: My focus and strength is here, and there is a very strong interest. We have a growing group of African-American collectors who have been supporting African-American artists and are totally open to artists of African descent, coming from Africa or the Caribbean. That audience is there, in New York, Washington, D.C.—everywhere. And what is really strong about them is that they are also . . . on boards and museum committees that can influence which artists are collected. It is much easier to grow and position African artists in the U.S. because of the flexibility of the market, the fact that it’s easy for a museum to just write a check—it doesn’t have to go through circles of logistics and government like you find in Europe.

El Glaoui: Do you think your gallery would be different if you had started in Paris, for example? Would your positioning be different toward the United States?

Ibrahim: Absolutely. I thought I was going to be exotic as a Parisian Somali opening a gallery in Seattle. But I realized no, I wasn’t—I became exotic coming from Seattle. I was actually planning a gallery in Paris because there is not a scene, which is strange. There are some galleries there, but serious galleries focused on contemporary African art in Paris? You can count them on one hand. I wanted to be in that situation, but I knew it was going to be tough with the Parisians. So my escape was actually good. In the end, now I’ve become a little brand—some people think there’s a huge African art market in Seattle, and I’m like, “No, it’s just me making some noise.” [Laughs.]

ARTnews: The 1-54 fair recently held its first edition on the African continent, in Morocco. How does response to the fair vary in different cities?

El Glaoui: The people we attract in America are totally different from the audience we attract in London. And the two things that are different between the Western fairs is that we’re not on the central stage in London or New York—we’re a satellite fair around Frieze. We wanted to leverage international collectors and institutions coming for Frieze, and it worked well. But the difference in Marrakech was that we were the main event in the city, with different partners and cultural platforms wanting to be part of what we were doing. This kind of collective effort is important for the future because that is when we see progress. The vibe was completely different—we felt the enthusiasm of Africans coming from all over the continent and people who have not been in London or New York who were proud of the first edition there. Marrakech, in a French-speaking country, attracted collectors we don’t touch in the others. The feedback from galleries was that they sold to people they didn’t know, and for a fair, that is important.

ARTnews: Mariane, you’ve participated in the Armory Show in New York for three years. How has your experience there evolved?

Ibrahim: This year was my third solo show of an African female artist, and it happened because I found the work relevant to what was going on. The first year was an invitation to a “Focus” section called African Perspectives, and I presented the work of the Nigerian artist Ruby Onyinyechi Amanze. The second year was Zohra Opoku in the “Presents” section, and we won the prize for the best presentation. And then this year was the work of the young Liberian artist Lina Iris Viktor as a choice that was close to the identity of the gallery being young. The idea of an art fair for me is that it’s showtime—this is what you have to show. Sometimes you sacrifice being super-commercial by minimizing the number of walls—in this case, I re-created my own wall on which I couldn’t even hang anything. The intention was not so much to make money as to establish the artist and myself.

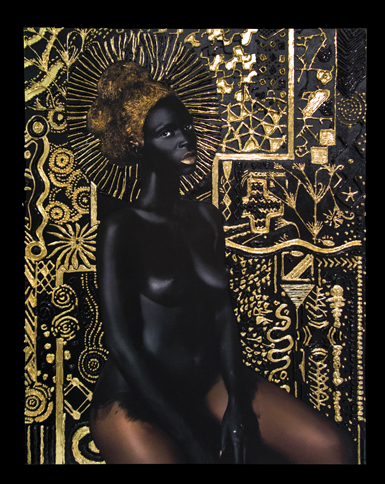

Lina Iris Viktor, Materia Prima II, 2017–18.

COURTESY MARIANE IBRAHIM GALLERY

ARTnews: You have talked in the past about how, for all the creativity there, Africa hasn’t reached its full capacity in terms of artistic production.

Ibrahim: The main problem in Africa is that the place of creation is not always the place of production. The infrastructure is not there, like studios and equipment to produce or make work. In the photography scene, 90 percent of all the photography is printed in Europe and America. Craftsmanship is in Africa, but it’s important that the circulation of objects and art come from Africa too. Then there’s visibility, but Instagram has democratized that. Now you can see whenever someone is making an object—you have all the details, and you can “like” it and grab it if you want.

ARTnews: Touria, what would you say is most needed in terms of infrastructure?

El Glaoui: There are more and more galleries on the continent to develop residencies for their artists with proper studios and provide materials they need to produce their art. But if you talk about ambitious projects—sculptures beyond what would be imagined or video projects or sound installations—a lot of those that have been successful were developed in residency programs abroad. Where can artists produce monumental pieces, and how would they ship from the continent? But as we’re talking right now, things are changing so fast. The level of schools, the level of teachers who are willing to come and share their expertise, the level of programs that are more and more easy to access—all of that allows an artist to stay on the continent and be inspired by his reality while still being able to be part of an international global platform.

ARTnews: There has been a lot of talk about the development of an African art history of a kind that has not yet been fully written. Where do you think we are on that trajectory?

El Glaoui: African art history has been written by the West around traditional artworks in museums that are not in Africa. They’re the ones who have the archives, the references, and the pieces to examine and write about. We’ve made progress with contemporary art and galleries engaging with publications and essays. I’m contacted every year now by students from all over doing thesis work on contemporary African art. But what’s interesting is that you see a lot of interest in certain art that belongs to museum collections and, therefore, the writing on particular artists belongs to the museum. That leaves out certain countries in Africa and major modern artists who should be archived and referenced. It is strange because we have a period of modern-contemporary art that started largely after colonial times. In terms of artists starting to have visibility, you’re really talking about the ’50s and ’60s; it’s just now that you have people researching artists from the ’20s and ’30s. In a way, market value triggered much more understanding and knowledge of artists and created a bit of a history for them. In many ways the market has positive influences or impacts when it comes to archiving, researching, and finding artists.

ARTnews: How does that relate to artists you work with at your gallery, Mariane?

Ibrahim: To be realistic, art is a luxury. It’s not something that everybody understands. Many people in Africa are in contact with forms of art, but getting an education purely on art means having access to a basic form of education—and points of reference such as museums and art centers where they can go and contemplate their heritage. But we all know what happened: with colonization, people excavated objects and their meanings and, out of context, fetishized them and put them in museums for us to contemplate and look at it as colonial trophies. You find African art next to the Oceanic art—why? Because they sort of look alike, though the only thing they have in common is white colonizers taking objects and de-rooting them to put them there. For the African population, that is a real disruption in terms of their relating to ancestry and being able to reflect on that.

I’ve heard museum directors say they will not loan works from their collection to museums in Africa because they’re scared they might not see them back. There is still litigation over what is stolen and what is not stolen. All of that is what artists are sitting with. And when the wave of modern artists came in and their art was taken out of the continent, we see the same thing again when objects travel without their maker. There is a rise now in artists who are conscious about the value of their art and its meaning, but beyond that, it’s a gray zone.

El Glaoui: I’ve visited a lot of universities on the continent that have good art programs, but their references are Western artists. Today, there are a lot of modern African artists who could be reference points as well, but they’re still studying from the books . . .

Ibrahim: Yes, who is publishing the books? Who is writing them? And what is the tone? What is the message being delivered? There has been a custom for African artists to wait for validation from Europe and America. But I think it’s important that this conversation stay within the continent. I’m always amazed by the confidence of certain European and American scholars meeting some place debating the future of African art. It’s like, “You are fantastic because you know probably more than we do.”

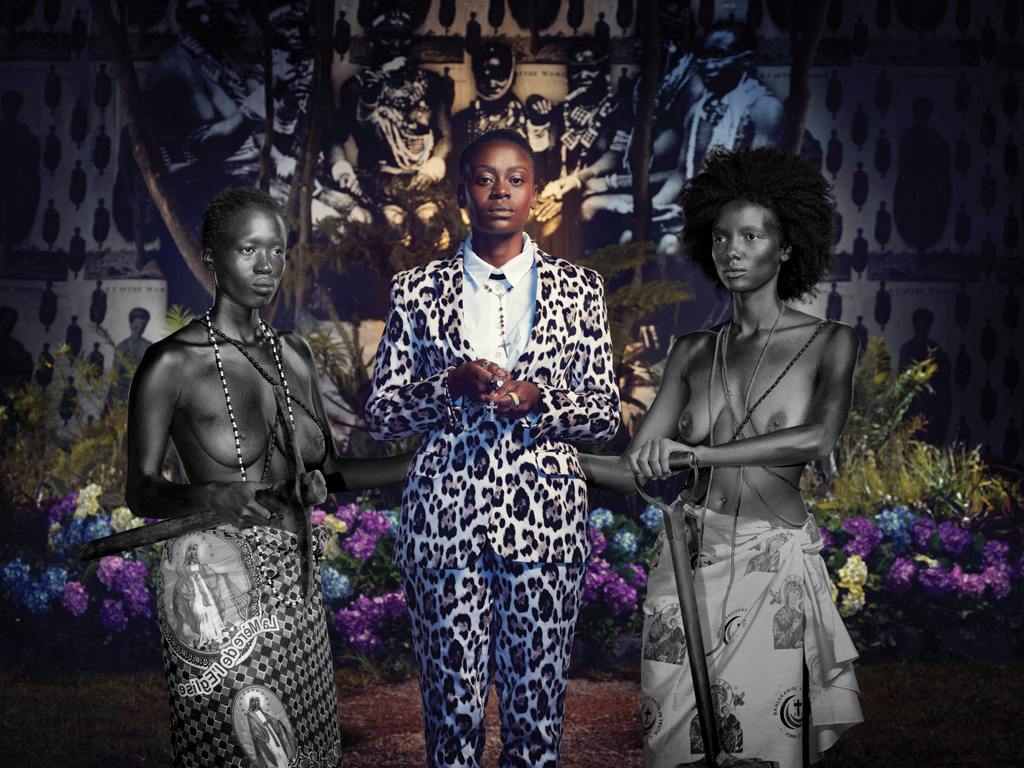

Kudzanai Chiurai, We Live in Silence IV, 2017, presented by Mariane Ibrahim Gallery.

COURTESY MARIANE IBRAHIM GALLERY

ARTnews: Fantastic?

Ibrahim: I’m being ironic.

El Glaoui: I went to this conference, “The Future of African Art,” at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art [in March in Kansas City]. There were a lot of representatives from Africa—but very specialized in traditional art.

Ibrahim: I know of some people who went there as a form of presence—they said, “We have to be there.”

El Glaoui: I had a different opinion. I thought it was interesting that we are dealing with our present reality and they are thinking about what they will do with their collections of traditional art.

Ibrahim: They’re never going to send it back [by way of repatriation].

El Glaoui: But it was interesting that they would even consider returning it—or letting them borrow it back. Someone was saying, “You know, there’s enough to return just 50 percent and still have plenty.” But like you said: maybe we should have our own conference, but we don’t.

Ibrahim: I wasn’t invited. It’s a choice that they have made to have certain people be a part of that conversation, and I doubt commercial galleries have any part. Talking about the future of a market, how do you measure that? Is it sales? Is it visibility in the media? How do you look at the future?

El Glaoui: In terms of the contemporary and commercial, I was the only representative. The rest were specialized in traditional art.

Ibrahim: What is the future of that “traditional”?

El Glaoui: That’s exactly what was raised, so I’m glad I was there. One of the main concerns is that it’s hard to attract an audience to see traditional art. If you go to the Met to see traditional African art, that section is empty most of the time.

Ibrahim: Because it is art out of its context. A kid who is eight years old in Kinshasa would look at art being in the Met as a victory, but he doesn’t have the ability to. People say they are going to create virtual tours, assuming everyone has fiber-optic internet to be able to see a 360-degree display. But to talk about returning art, with time, it will happen—I am optimistic about that. But even if they return it, is there an infrastructure to welcome it? That is a conversation that needs to happen on both ends. Museums are not just going to send objects back and not know where they are going to be and how they’re going to be maintained. But this is not my domain of expertise—I’m talking as a pan-African who wants the traditional perspective and contemporary art to coexist.

ARTnews: How has the rise of market attention and institutional support affected artists and what they make?

Ibrahim: My sense—and I might be wrong—is that African artists are doing better and bigger things because they know they have a chance to have their work in museums. And the fact that their work is supported by collectors also gives them the means to go beyond and reinvest in their own practice and production. I have noticed that artists I work with are like, “Yes, I feel a little bit confident—I’m going to use this material and I’m going to try this . . .” I’ve seen a lot of renewal, and less redundancy in terms of what they’re doing and different kinds of collaborations they are engaged in. I think that is because there’s a favorable market for them to be able to be close to their full potential.

The 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair in Marrakech.

COURTESY THE 1-54 CONTEMPORARY AFRICAN ART FAIR

ARTnews: Does the location of their market matter?

Ibrahim: The U.S. market is refreshing, and other markets are showing great interest. I was at the Zona Maco fair [in February] in Mexico City, where I know they are not exposed to contemporary African art, and the response was absolutely amazing. They were as excited about African art as any other type of art. The geographic background is what I’m trying to push more and more. I don’t want it to be like the way women artists used to be called “feminist artists” when they were just women. But I think it’s necessary to call it “African contemporary art”—it’s a necessary pain for us to be more and more global. There’s going to be a time when that will not matter—when the fact that an artist is from Zimbabwe or England or Mexico will not matter anymore. But for now I think it’s important to introduce those artists within their geography. I don’t know—what do you think about that?

El Glaoui: I completely agree. I don’t see that time coming very soon, but I do believe it will happen eventually. I hope so.

ARTnews: How do you go about courting collectors on the continent?

Ibrahim: I have been happy to have met a lot of African collectors who have been supportive this year, and I think they are coming into the game while wanting to be associated with the movement and also socially involved. I also think it’s important that there is a good diversity of African and non-African collectors.

El Glaoui: I think we all have the same mission of nurturing this collector base. But it is a question about their practice and how they collect today, because often there’s no gallery or no institution—they’ve been in a direct relationship with the artists and supporting their work, so it’s difficult to know them until you are visiting their city or their country and people introduce you.

Ibrahim: I’m also delighted to notice that artists on the continent are becoming more and more professional in terms of managing their studios and dealing with inquiries from collectors and museums. It’s not falling to stereotypes of going in the back of a shop and saying, “Hey, what do you have in here?” I know some artists who say, “You like this piece? Contact my gallery in London and then maybe we can ship it to you back here.”

El Glaoui: The story is different for artists who are new and young or coming out of school, with a different environment to think about.

ARTnews: What areas in Africa most excite you in terms of activity for galleries and institutions?

El Glaoui: I’m very supportive of Morocco right now because I’m amazed by what I saw in the contemporary art scene when I was there. The support they’re getting is important, so I can see it evolving in a good way. In Ghana, Gallery 1957 is really moving things around, bringing the support not only to produce artwork but to sell it abroad. Ghana also has Kwame Nkrumah University—it’s called a “science and technology” university, but it has produced some of the best artists of the past generations. If you’ve never been, you have to go to South Africa. There’s history there, and the art scene is rich and exciting. Nigeria, Tunisia, Kenya . . .

Ibrahim: I just came back from the place where I grew up, which is called Somaliland—an unrecognized state below Somalia and Ethiopia. The youth there have the urge and desire to go to art spaces, and I was very much touched by that. Here we are in New York with all of these spaces and all this diversity, and then there are certain countries that are really desiring that. There are so many places to go in Africa, but I urge people to go to Dakar for the Dak’Art Biennial. It’s a wonderful week to be introduced to Africa and to Senegal, which is rich in history and a peaceful country where different religions and ethnic groups coexist. If you are an art aficionado you are able to do basically three things at the same time: discover a place, get connected with art, and also network and see who is who—and be part of a conversation. One country I haven’t gone to and would love to is Rwanda, where I hope to go this year or next. I envy anybody who has not had an African experience because, once you get into it, it can be addictive. You want to go back.

A version of this story originally appeared in the Summer 2018 issue of ARTnews on page 46 under the title “Touria El Glaoui & Mariane Ibrahim.”

[ad_2]

Source link