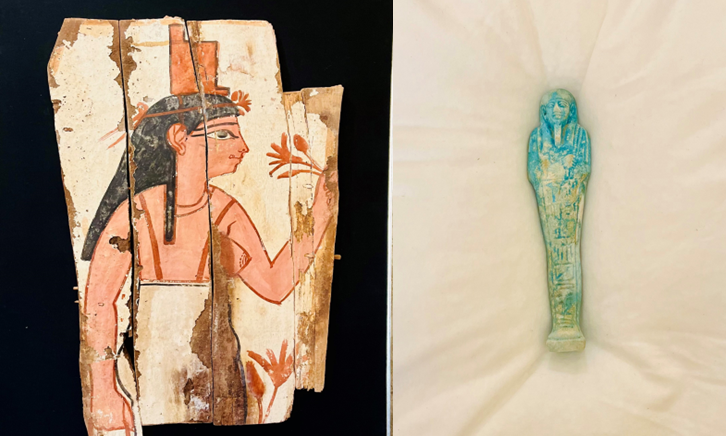

Two of the three returned objects: a painting of the goddess Isis from a sarcophagus, dated from the Roman period of 30BC to 642AD (left) and a faience shabti, or grave statue, for Ipethemetes from Thebes—understood to date from the 26th dynasty (664 to 525 BC) (right)

Courtesy of the Information and Heritage Inspectorate

Three looted objects from ancient Egyptian graves, including a mummified head, have been ceremonially returned to Egypt from Dutch collections.

The Netherlands’ information and heritage inspectorate announced this week that it had signed over ownership of a faience shabti, or grave statue, for Ipethemetes from Thebes—understood to date from the 26th dynasty (664 to 525 BC). It did the same for a painting of the goddess Isis from a sarcophagus, dated from the Roman period of 30BC to 642AD. A mummified head dating from around 170-45BC, meanwhile, has also been restituted.

The shabti and the painting are believed to have been illegally exported from Egypt after grave robberies in 2014 and were discovered by Dutch police in the possession of an art dealer, who agreed to return them. They were returned in accordance with the Unesco 1970 convention against illegal trafficking of cultural property.

The mummified head had been in a collection in the Netherlands and was returned voluntarily by the heir who inherited it.

Ben van den Bercken, the curator of the ancient Egyptian collection at the Allard Pierson museum, who was at the ceremonial handover from the Netherlands to the Egyptian ambassador to the Netherlands last Friday, said there is a changing view of these kinds of objects.

“Especially in the past few years, there is more attention for the actual provenance of heritage material and how it ended up with museums or with private collectors on the art markets… and a lot more communication with the source countries on how to right situations that are considered wrong nowadays,” he said.

Images of the mummified head—which is severed from its body—have not been shared publicly, with these kinds of considerations in mind. “At the Allard Pierson, in our recent exhibition on mummy portraits, we tried to create awareness of what we are actually displaying in a museum when we are talking about mummified remains—remains of people,” he said. “This has to do with respect for those people.”

The painting of Isis—considered a protective goddess—was, he said, “a very fine example” from a Roman-period painted coffin, created on planks of wood covered in plaster with pigment such as ochre and black carbon. The faience shabti, a naturally glazed statue of someone who had died, was created to do that person’s work in the afterlife, through a spell from the Book of the Dead.

In a statement, the Dutch inspectorate stressed the importance of continuing such restitution work in relation to Egyptian artefacts. “Egypt, one of the oldest civilisations in the world, has a rich history dating back to around 3300 BC,” it said. “The country's cultural riches put it at risk of illegal excavations, theft and plundering. International cooperation is the only way to combat these threats and ensure that unlawfully exported objects are returned.”