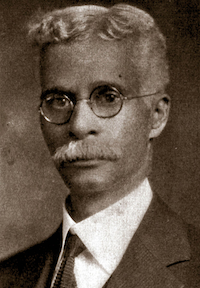

Thomas Fountain Blue, the first African American to head a public library in the United States, was also a civic, educational, and religious leader. Blue was born in Farmville, Virginia, on March 6, 1866, to Noah Blue, a carpenter, and Henry Ann Crawley Blue. They were parents of two other children, Alice Blue and Charles Blue.

Blue enrolled in Hampton Institute in Hampton, Virginia, in 1885 and graduated in 1888. In 1894, he enrolled in Richmond Theological Seminary (now Virginia Union University) in Richmond, Virginia, finishing in 1898 with a Bachelor of Divinity degree. One week later, when the United States declared war on Spain after the sinking of the USS Maine off the coast of Cuba, touching off the Spanish-American War, Blue joined the Sixth Virginia Volunteers battalion comprising African American soldiers and was stationed first in Camp Poland in Tennessee and later at Camp Haskell in Georgia.

In 1905, Blue was selected to lead the Western Branch Library of the Louisville Free Public Library on South 10th and Chestnut Street, the first Carnegie Library in the nation to serve African American patrons with an exclusively African American staff. The facility cost $31,024.31 to build and when completed had over 4,000 books and 53 periodicals.

In 1914, Blue opened Louisville’s second Carnegie Library for African Americans, the Eastern Branch Library. During World War I, Blue was drafted, left the branch, and was appointed the Education Secretary at Camp Zachary Taylor in Louisville, one of sixteen national Army training camps created across the nation. Blue worked with Black troops who mostly had supporting and laboring roles in the United States.

After the war ended in 1918, Blue returned to Louisville, and a year later, in 1919, he was named head of the “Colored Department” for the city’s public library system and supervised eight African American assistants. The Colored Department was the first in the United States to have a staff which served multiple Black library branches.

In 1922, Blue was a presenter at the American Library Association Conference in Detroit, Michigan, where he gave a paper titled, “Training Class at the Western Colored Branch,” and led the subsequent discussion with the Negro Roundtable composed of other African American Library staffers from across the nation.

On June 18, 1925, Blue married Cornelia Phillips Johnson from Columbia, Tennessee, and they parented two children, Thomas Fountain Blue, Jr., and Charles Blue (named after his younger brother). Two years later, in 1927, Blue founded the Negro Library Conference and conducted its first meeting at Hampton Institute.

Later becoming a minister, Reverend Thomas Fountain Blue—who held membership in the American Library Association, the Special Committee of Colored Ministers of Louisville on Matters Interracial, and was a charter member of the Louisville Chapter of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History—died on November 10, 1935, in Louisville, Kentucky. He was 69.

At the 2003 joint conference of the American Library Association with the Canadian Library Association Annual Conference at the Metro Toronto Convention Centre in Toronto, Ontario, Blue was posthumously honored when the organization passed a resolution recognizing his leadership in promoting professionalism among the staff of African American libraries across the United States. In 2022, a headstone honoring Blue and his wife, Cornelia Phillips Johnson, was placed at Eastern Cemetery in Louisville by the Frazier History Museum.

Do you find this information helpful? A small donation would help us keep this available to all. Forego a bottle of soda and donate its cost to us for the information you just learned, and feel good about helping to make it available to everyone.

BlackPast.org is a 501(c)(3) non-profit and our EIN is 26-1625373. Your donation is fully tax-deductible.

Lillian Taylor Wright, “Thomas Fountain Blue, Pioneer Librarian, 1866-1935,” https://radar.auctr.edu/islandora/object/cau.td:1955_wright_lillian_t; “Louisville Western Archives (LFPL) – The Reverend Thomas Fountain Blue Papers,” https://kdl.kyvl.org/digital/collection/lfpl-revblue; “Thomas Fountain Blue,” https://friendsofeasterncemetery.com/thomas-fountain-blue/.

Your support is crucial to our mission.

Donate today to help us advance Black history education and foster a more inclusive understanding of our shared cultural heritage.