[ad_1]

But for every story that makes the news, there are countless others that don’t involve police. Black customers who get followed too closely by store employees. Hispanic students and Muslims who get asked if they’re really American.

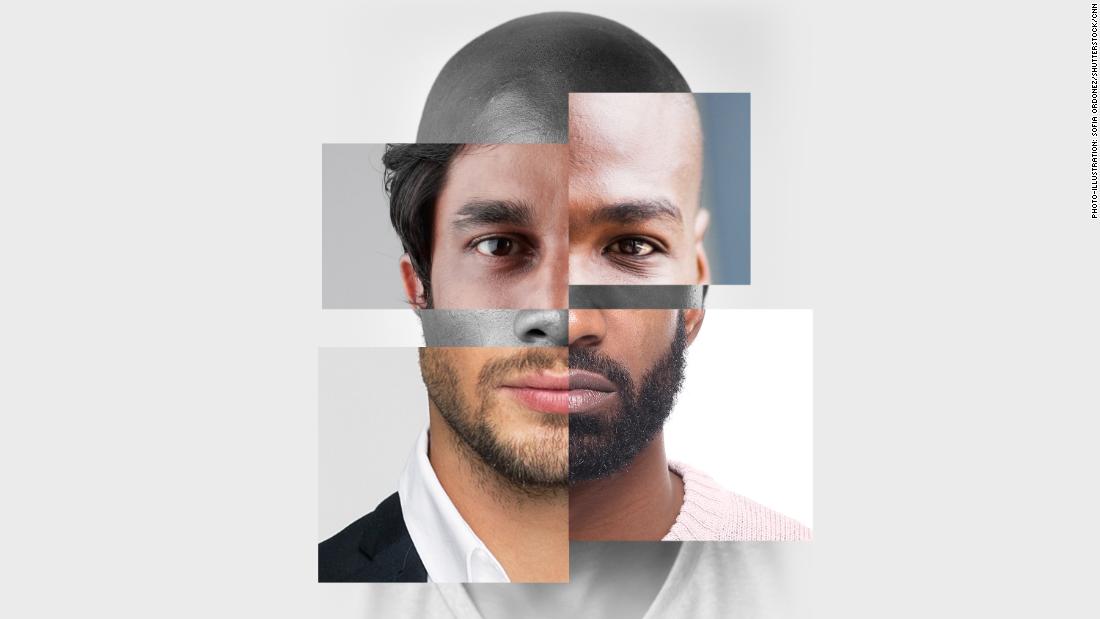

This is everyday racial profiling — and it doesn’t just hurt the victims. It has an insidious ripple effect on the rest of society — in business, health and public safety.

Everyday racial profiling is “almost second nature now,” said Darren Martin, a 29-year-old black man.

Late last month, he was moving into his own New York apartment when a neighbor called police saying he was an armed burglar.

Martin still has no idea what his neighbor could have mistaken as a weapon.

“It could have been the TV, the couch, the pillows — I don’t know,” he said. “It’s a fear of black men that makes people see things. I didn’t have weapons. I just wanted to move home.”

For people of color, everyday racial profiling is one indignity piled atop another.

When he’s leaving a store, Martin often hears the same line: “Sir, can you please turn around and show me what’s in your pocket?”

“It’s dehumanizing,” he said.

The consequences can be dangerous

The day Martin moved in, about a half dozen New York police officers showed up under the impression he was armed. Had he made one wrong move, Martin said, he could have been killed.

But there’s a hidden and much more common danger to racial profiling — long-term health problems.

Racial profiling impacts white people, too

Godsil urges white people to think about what it must be like to live under a cloud of suspicion. “That’s something that those of us who are white never have to think about,” she said.

As director of research for the Perception Institute, Godsil said racial profiling has a broad ripple effect on everyone.

“Even if it happens to someone that doesn’t look like you, it’s a harm to the community,” she said.

For example, many calls about a “suspicious person” don’t really involve suspicious activity — just a person of color walking down the street.

This kind of racial bias wastes officers’ time and resources, which could be spent actually protecting communities.

On a more personal level, those holding racial biases are actually harming themselves, too.

When you start feeling anxiety about someone’s race, Godsil said, it triggers the amygdala — the part of the brain that’s activated by fear.

“That’s a higher level of stress on your body,” she said.

“In addition to reducing the harm of bias to those being stereotyped, de-linking races with negative stereotypes would be a physiological benefit to those holding the bias. … If people can begin to let go of the fear, it will benefit them personally as well.”

Biases often begin at a young age

And the seeds of bias are often planted in our heads before kindergarten.

Those environmental triggers can come from verbal slurs, ethnic jokes and acts of discrimination. And “mass media routinely take advantage of stereotypes as shorthand to paint a mood, scene or character.”

Once embedded, these biases are hard to shake.

“Stereotypes and prejudices resist change, even when evidence fails to support them or points to the contrary,” Teaching Tolerance says.

But there are ways to fight back

— Exposing kids to more positive images of other racial groups

— Helping your kids develop diverse friendships

— Cultivating your own diverse friendships

— Talking openly about race and the effects of racism

Whatever you do, don’t try to pretend prejudices don’t exist.

“People who argue that prejudice is not a big problem today are, ironically, demonstrating the problem of unconscious prejudice,” Teaching Tolerance said.

“It seems as a black person, you can’t live. There’s nothing you can do without calling the cops,” she said. “This is getting out of hand.”

[ad_2]

Source link