[ad_1]

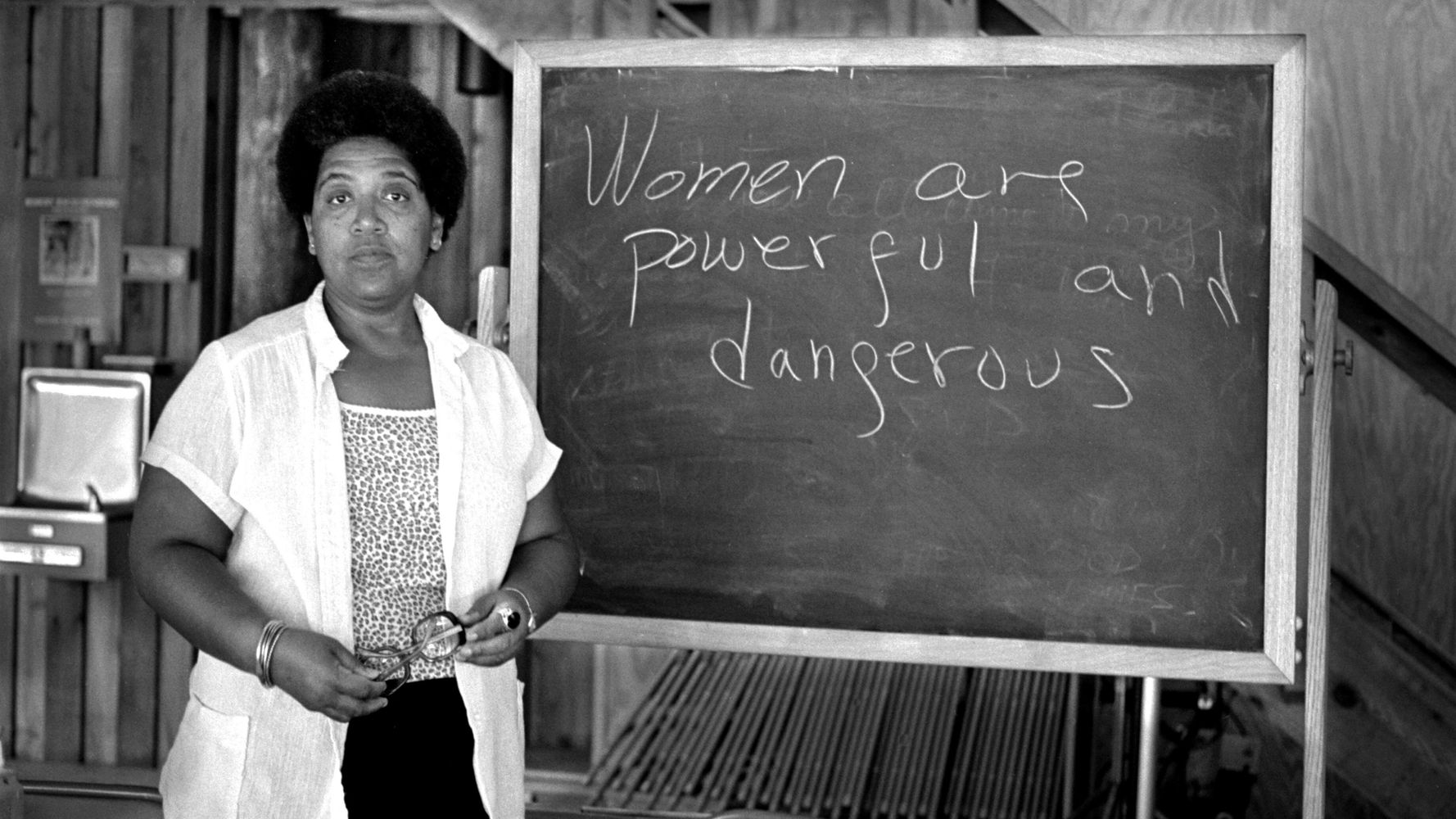

Books by some of the most famed Black feminist writers in the U.S., including Patricia Hill Collins, Audre Lorde, bell hooks and Angela Davis, were published in Brazil last year — more than three decades after the works first entered the feminist canon.

“I believe these releases are due to publishers realizing that Black women are interested in books that analyze specific issues related to their own experiences,” said journalist Stephanie Borges, who translated Lorde’s acclaimed work “Sister Outsider” into Portuguese.

That book, widely considered the activist’s most important work, was published in the United States 35 years ago. Until last year, Lorde’s writing had only been translated into Portuguese in collections or cited in thesis projects by Brazilian researchers. ”Sister Outsider” is a collection of 15 articles from Lorde, who describes herself as a “black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet” and introduces the idea of the “outsider” to embody a distant and nonhegemonic view of racism and sexism.

The omission of Audre Lorde’s work in Brazil was notable enough that publishers decided to get involved. “[We] were committed to filling a void, to make it easier to access diversity and the wealth of feminist output in Brazil and throughout the world,” said Rafaela Lamas, editor and coordinator of publishing house Autêntica’s éFe collection, which features prominent women writers.

Collins and Davis both traveled to Brazil in October as the Portuguese editions of their books — “Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness” and the Politics of Empowerment” and “Angela Davis, An Autobiography,” respectively — were published.

[We] were committed to filling a void, to make it easier to access diversity and the wealth of feminist output in Brazil and throughout the world.

Rafaela Lamas, Brazilian editor

“We shouldn’t need to be Michelle Obama to have our books published,” Collins told HuffPost Brazil, alluding to the global popularity of the former first lady’s memoir, “Becoming.”

In her work, Collins, who was the first Black woman to preside over the American Sociological Association, underscores the importance of intersectionality within the feminist movement — an analysis of how racial, gender and class oppression are interconnected.

Historian Raquel Barreto, who wrote the preface to the Brazilian edition of ”Angela Davis, An Autobiography,” said few books of this kind have been written by women, and even fewer by Black women.

“[Davis] addresses the lack of texts written by Black women who write about themselves, think about themselves, but observe the world around them,” Barreto said. “In Angela Davis’ case, she is talking about the context of the ’60s and ’70s, and contesting the prevailing narrative about that period.”

Four books by bell hooks — the pen name used by professor and activist Gloria Jean Watkins — were also published in Brazil last year.

Bhuvi Libânio, who translated hooks’ classic “Ain’t I A Woman?” into Portuguese, cited Afro-Brazilian writer Conceição Evaristo to explain the exclusion on Black writers from the country’s canon.

“Conceição Evaristo said: ‘Because of racism, the Brazilian imagination can’t recognize that black women are intellectuals,’” she said. “The publications we have today are just the beginning. We need even more books.”

“Ain’t I A Woman?,” originally published in 1981, is inspired by Sojourner Truth, a former slave in the U.S. who became an orator after she was freed. In an 1851 speech at the Women’s Rights Convention, she denounced the fact that white suffragettes and abolitionists excluded Black and poor women. hooks’ work explores the racism and sexism that existed from Truth’s era through the 1970s.

“Those works encourage critical thinking, and it is only with that, with a great deal of reflection and dialogue — ever more dialogue — that we will be able to break down the barriers that separate us and build the bridges to freedom that we need,” Libânio said. “Those women, along with so many others, live (or lived) the struggle for freedom through talk and in action.”

A New Perspective

Perhaps as a result of the so-called “Feminist Spring” that started in 2015 in Brazil, established publishers and independent presses have developed an interest in bringing the feminist discourse to a broader audience.

However, Borges said publishing the works of Black feminist writers in Brazil doesn’t necessarily mean there’s a wide appreciation for feminist thought in the country.

“Unfortunately, we still have small editions in an enormous country,” she said.

“Yet I think that the publication of Davis, hooks, Lorde, and Hill Collins can be linked to the presence of more young Black women in universities,” she added. “When those titles are not assigned in the classrooms, they understand that certain things are not going to come through the regular institutional channels, so they go after them on their own.”

Barreto had a similar opinion.

“[There is] a problem with the publishing market in that intellectual output produced by Black [people] is invisibilized and forgotten,” she said. “Especially if it is written by Black women.”

“It is important to [publish books by Black female authors] because it responds to a need for better education that all of us — not just Black people — need, in order to have points of reference,” Barreto said. “People need to move out of that mindset that it is just the white man, a certain type of white man, who writes and discusses the narratives about the world, who generates thought.”

People need to move out of that mindset that it is just the white man, a certain type of white man, who writes and discusses the narratives about the world, who generates thought.

Raquel Barreto, historian and researcher

For Giovana Xavier, a professor and historian from the University of Brazil, the rise of this American Black feminist thought in Brazil is a good thing and the result of affirmative policies, like quotas in the universities. Still, she said, it needs to be approached with a degree of skepticism.

“It became impossible to ignore the work involved and how significant Black women’s contributions were, beyond the movement, in order to think about the world,” she said. “As a professor, I’m tired of translating passages from [Collins’] books on my own, and even [Davis’] that have not yet been translated.”

“It’s important to be able to go into a bookstore and see these titles displayed. That is something really new, just in the past five or 10 years,” Xavier said. “But I also think about the impact that this has in reality. Because the publishing market makes choices. People in Brazil still know Angela Davis better than they know Conceição Evaristo and Carolina Maria de Jesus, for example,” she added, referencing Black Brazilian feminist writers.

In fact, many of the experts interviewed by HuffPost Brazil pointed out that Afro-Brazilian intellectuals like Lélia Gonzales, Beatriz Nascimento and Sueli Carneiro, who studied women’s lives in Brazil, still haven’t seen mainstream success. Their works had been published independently, and by Black Brazilian-run presses and newer imprints.

“Even today you’d have a hard time digging up the writings of Lélia Gonzales or Beatriz Nascimento, two women who are extremely important to Brazilian feminism, and are even mentioned by Angela Davis,” Xavier said.

For her, access to these authors is important so that more people, even if they aren’t in academia, can read the words of Black authors who reaffirmed their own histories and conceived another world view.

“The fact that we have more access to Davis than to those Brazilian women says something, right?” Xavier said. “It’s interesting to think about that. Why is the content created by the Brazilians confined to blogs, to activist media, for example? Those spaces matter too, of course. But it is also important that these books are able to be a part of the established publishing world.”

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link