[ad_1]

Not The Nation recently published a poem in which a homeless narrator speaks a complex, nuanced variety of English with a long and interesting history.

The variety of English is Black English, and the poet is Anders Carlson-Wee, a white man. In the wake of the controversy, The Nation’s poetry editors have appended a kind of trigger warning to the poem calling its language “disparaging.” (They also apologized for its “ableist language;” the poem used the word “crippled.”) Carlson-Wee has dutifully, and perhaps wisely, apologized that “treading anywhere close to blackface is horrifying to me” and declared that the poem “didn’t work.”

However, I suspect that many are quietly wondering just what Carlson-Wee did that was so wrong—and they should.

The primary source of offense, in a poem only 14 lines long, is passages such as this, in a work designed to highlight and sympathize with the plight of homeless people: “It’s about who they believe they is. You hardly even there.” The protagonist is referring to the condescending attitudes of white passersby who give her change. Yet Roxane Gay, for example, directs white writers to “know your lane,” and not depict the dialect.

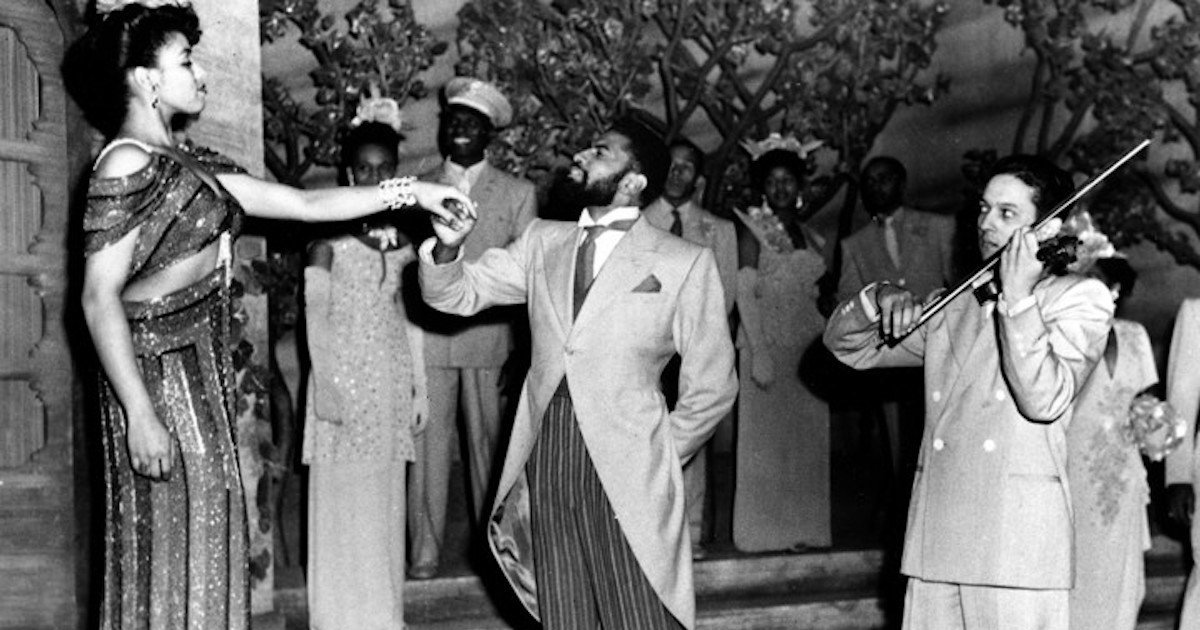

To be sure, America long harbored a tradition of mocking black speech in exaggerated “minstrel” dialect. Minstrel shows highlighting this kind of talk, full of “am” used in all persons and numbers, and mangled words such as “regusted” for “disgusted” (that one used as late as the 1940s on the radio show Amos n’ Andy, in which white men portrayed black ones), were central to American entertainment well into the 20th century.

[ad_2]

Source link