[ad_1]

Several days after police killed George Floyd this spring, civil rights hero Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.) lamented that too little had changed since a white mob lynched 14-year-old Emmett Till in 1955.

“Despite real progress, I can’t help but think of young Emmett today as I watch video after video after video of unarmed Black Americans being killed, and falsely accused,” Lewis said in a May 30 statement. “My heart breaks for these men and women, their families, and the country that let them down — again.”

Lewis, who died last Friday at age 80, had fought for the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964. He’d led the “Bloody Sunday” march for voting rights in Selma, Alabama, in 1965, when the brutal response of law enforcement gained national attention. And this year, he again called on people of “all faiths and no faiths, and all backgrounds, creeds, and colors” to take up the fight for racial justice.

In the 58 days since police killed Floyd, the Black Lives Matter movement has won some victories. Cities across the nation have begun to rethink policing, officers involved in Floyd’s death have been arrested and charged, and long-standing racist monuments have been taken down. But there’s much left to do, and historians note that if the past is a guide, the movement is still gaining momentum.

“We are still in the middle of this moment,” said Charles McKinney, a professor of African American history at Rhodes College.

Just like in the past, photos and video footage have shown what the Black Lives Matter movement is saying ― from the May 5 cellphone video of armed white men in a suburban neighborhood in Georgia chasing and gunning down Ahmaud Arbery to the footage of the last breathless minutes of Floyd’s life. Though Americans have long known about systemic racism and have seen instances of police brutality before ― “250 million white people didn’t wake up three months ago and say, ‘Oh my god, police brutality is a thing?’” McKinney said ― these latest images have forced a mainstream conversation.

But as McKinney noted, “Images don’t necessarily translate into automatic slam-dunk wins and victories.”

“These moments where we have video footage of people ― Black people in particular ― being murdered, those images can be widely disseminated. There can be lots and lots of conversations about what we have seen. People can be mad, sad, outraged, angered, disappointed,” he said. “We go through all those cycles, and at the end of the day, it is still an open question of whether or not the murderers will be brought to justice and if systems can be altered and shifted and improved for the better.”

Aaron Bryant, social justice curator for the National Museum of African American History and Culture, said that while Black Americans may not be optimistic that change will occur quickly, they are hopeful it will come someday.

“People haven’t given up hope on the American promise or their rights to full citizenship as Americans, and I think that is really important,” Bryant said.

Both hope and stamina are crucial, he said, because “this whole idea of freedom and progress is really through struggle. And there will always be struggle.”

It has been 65 years since Till was murdered, and the fight for civil rights and social justice has continued. Here are some of the key moments:

August 1955

Emmett Till was beaten and killed in Mississippi after a white woman falsely accused him of sexual harassment. He was 14. His murderers were acquitted. The brutality of his death and the publicity that followed sparked outrage and forced America to look at the enduring violence against Black Americans.

December 1955

Rosa Parks, a Black woman in Montgomery, Alabama, refused to give up her seat on a public bus to a white person, a requirement under city segregation laws. This led to her arrest. The NAACP organized a one-day boycott of the bus system, which ultimately continued for 382 days. Later, when reflecting on her actions, Parks said, “I thought of Emmett Till, and when the bus driver ordered me to move to the back, I just couldn’t move.”

November 1956

The Supreme Court affirmed a lower court ruling that segregation on public buses was unconstitutional. It ordered Montgomery to integrate its bus system in December, ending the boycott.

February 1960

Black college students Ezell Blair Jr., David Richmond, Franklin McCain and Joseph McNeil organized a sit-in at the Woolworth’s lunch counter in downtown Greensboro, North Carolina. Staffers refused them service, but the students refused to give up their seats. The Greensboro Four, as they were later known, were spurred to action by Till’s murder. Sit-ins spread throughout the nation and participants faced fines, arrests and, in many cases, violence.

July 1960

In the summer of 1960, after tens of thousands of students had joined the sit-ins, many dining facilities were integrated, and at the end of July, the lunch counter at Woolworth’s was finally open to Black patrons as well as white ones.

May 1961

The Freedom Riders sought to test the Supreme Court’s 1960 decision in Boynton v. Virginia, which held that segregation of interstate transportation facilities, including bus terminals, violated federal law. Civil rights activists rode interstate buses throughout the American South, using those facilities the court had ordered to be integrated to challenge the non-enforcement of the court’s decision. The protesters were met by arrests, violent attacks and angry white mobs.

November 1961

The Interstate Commerce Commission issued regulations banning the segregation of all interstate buses, trains and air terminals, causing signs indicating “colored” and “white” sections to come down all through the South.

April 1963

Black men, women and youth took to the streets in Birmingham, Alabama, for peaceful protests. They were met with violent attacks ― including high-pressure fire hoses and police dogs ― which produced some of the most memorable and troubling images of the civil rights movement. The protesters were calling for desegregation in the city.

May 1963

A month later, the city desegregated lunch counters, removed “White Only” and “Black Only” signs from restrooms and drinking fountains, and released a Negro Job Improvement Plan, which focused on employing Black workers.

March 1965

Three times that month, protesters set off on a 54-mile walk from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital of Montgomery, as part of an effort to register Black voters in the South. They were repeatedly met with violence, most infamously on “Bloody Sunday,” when officers tackled the marchers to the ground, chased them down with horses, beat them with whips and batons, and used tear gas. But after Bloody Sunday, the marchers picked themselves up and tried again and again. The third march reached Montgomery.

August 1965

Following years of struggle to secure Black Americans’ right to vote, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was signed by President Lyndon Johnson.

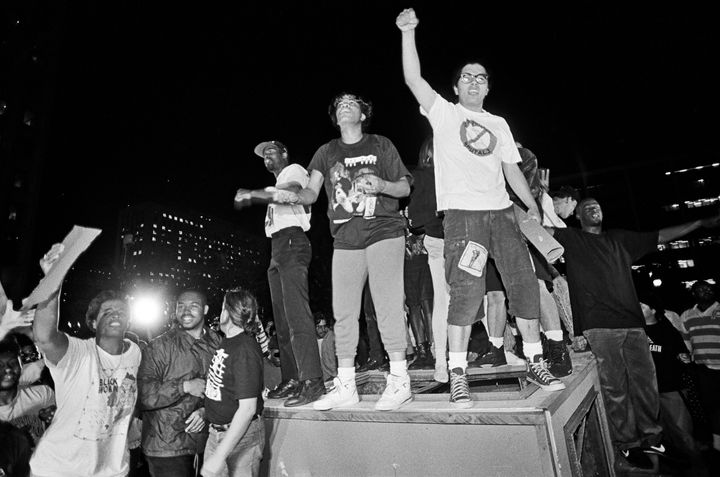

April 1992

Los Angeles erupted into protests over the acquittal of police officers who beat Rodney King ― video of that assault on a Black man became a media sensation ― as well as the probation order for a store owner who had shot and killed a 15-year-old Black girl, Latasha Harlins. Once the protests turned violent, looting and burning followed. After six days of unrest and efforts to quell that unrest, 63 people were dead and over 2,000 injured.

November 2000

The Rodney King beating set off a yearslong effort to reform the Los Angeles Police Department. The Christopher Commission was established even before the 1992 unrest to conduct a full examination of LAPD operations. Its July 1991 report laid out the widespread use of excessive force throughout the department. Five years later, the U.S. Department of Justice began investigating the department. In May 2000, it said it had found “a pattern or practice of excessive force, false arrests, and unreasonable searches and seizures.” The Justice Department made reform recommendations, and in November 2000, it reached a consent decree with the city allowing for five years of independent monitoring.

February 2013

George Zimmerman, a neighborhood watch volunteer in Florida, fatally shot Trayvon Martin, a Black teenager who was on his way home from the convenience store. Even after the 911 dispatcher told Zimmerman not to pursue the “suspicious person” he reported, Zimmerman trailed and shot Martin. The 17-year-old was carrying an iced tea and candy. Protests followed as the nation once again grappled with racism and injustice. But Zimmerman was acquitted in court.

July 2013

The hashtag #BlackLivesMatter was first shared on Twitter. It ultimately became the name of an activist organization and the shorthand for a movement.

August 2014

After an officer shot and killed Michael Brown, a Black teenager, protests flared up across Ferguson, Missouri, and were met with a violent police crackdown watched across America. The unrest in Ferguson and elsewhere became a turning point in the conversation about race. One of its major outcomes was dubbed the “Ferguson Effect” ― the theory that the exposure of police brutality cultivated by media coverage of the protests led to increased levels of distrust in the police among Americans.

July 2014

In the midst of an arrest, a New York police officer used a chokehold on Eric Garner, a Black man, even though that tactic had been banned by the police department. The officer continued to hold Garner on the ground even as he desperately cried “I can’t breathe” over and over. Bystanders caught it all on video. Protests erupted across New York after a grand jury declined to indict the officer, Daniel Pantaleo, who killed Garner.

August 2019

Five years after Garner died, the NYPD finally fired Officer Pantaleo.

May 2020

After a Minneapolis police officer knelt on George Floyd’s neck and killed him, the nation responded in widespread protests. People in all 50 states joined in Black Lives Matter demonstrations, even in small rural communities where such protests seemed inconceivable just one year before. The recent deaths of Arbery in Georgia at the hands of armed civilians and Breonna Taylor in Kentucky by police executing a no-knock search warrant also fueled the protests. Americans who had lived the Black Lives Matter movement were joined by others who were finally seeing the truth.

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link