[ad_1]

By Stephen Janis and Taya Graham

Special to the AFRO

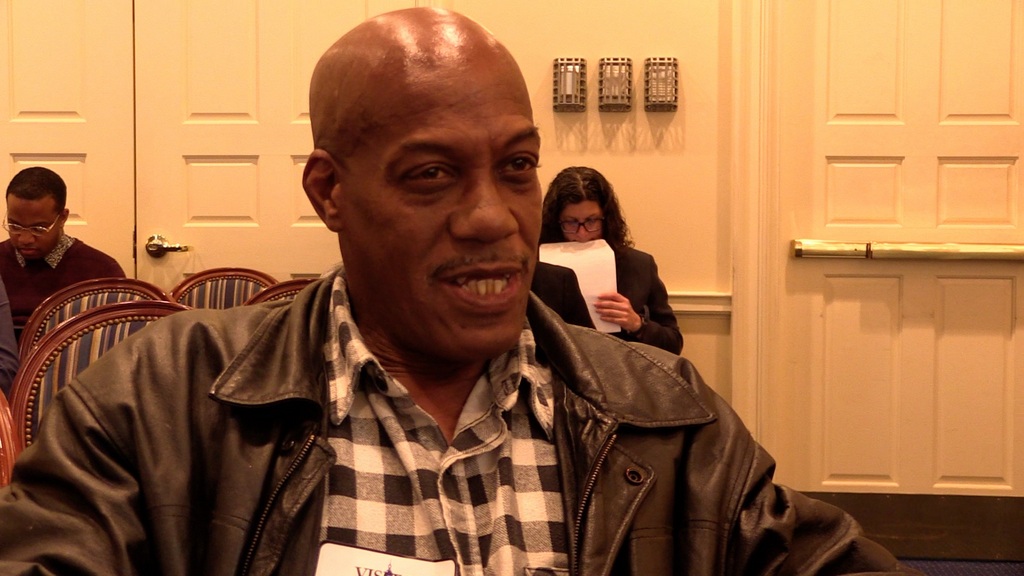

Stewart Jones is decades removed from his minor encounter with Maryland’s criminal justice system; but the consequences for his life outside of prison continues to linger.

“I wanted to do the right thing, but it was so hard to get a job,” he told the AFRO while waiting to testify before the House Judiciary Committee March 10.

Convicted of two minor theft charges for shoplifting to support his drug habit, he served his time and was released in the late 1990s.

But, because the crimes were classified as felonies, the charges stayed on his record. And that meant Jones couldn’t get a job.

“I got depressed, I never really got a job where I could sustain myself,” he said. “There are no second chances here.”

Jones’ story is one of the reasons expungement is again on the agenda in Annapolis, and why he was attending the House Judiciary Committee hearing on a bill that would make it easier to remove certain types of charges from the public record.

The focus this year is to pass legislation that will address what’s known as unit expungement, a phenomenon that arises from prosecutor’s penchant to pile on charges against defendants, many of which are ultimately dismissed.

“Prosecutors will put up five or six charges based around one offense, they get a conviction on one, but the other five are not expunged,” Kimberly Haven, Coalition & Policy Director for Reproductive Justice Inside, an organization which advocates for incarcerated women.

Haven says the practice of adding charges that are usually dropped, let alone never adjudicated can be especially burdensome for people trying to rebuild their lives post-incarceration.

“They should be automatically expunged. We need to do everything we can to help people come back,” she said.

The push to enact more progressive policy with regards to Maryland’s criminal justice system comes as Republican Governor Larry Hogan is pushing for more tough on crime measures.

Recently he introduced a crime package that includes longer sentences for gun crimes and less leeway for judges when it comes to sentencing.

However, activists pushing for more reform say there is little evidence these policies work.

Dayvon Love, Public Policy Director for Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle says the data shows no correlation between harsher sentences and reduced crime.

“There is no relation between get tough policies and reduced crime,” Love told the AFRO.

Looming over the proceedings is how race informs criminal justice policy in Maryland, which has led to more significant consequences for the state’s African American population.

As of 2019, Maryland incarcerates the highest proportion of Black people in the United States. The latest statistics show that roughly 72 percent of all inmates are Black. It’s a figure that outpaces Southern, allegedly more conservative states like Louisiana.

But, it’s an idea that Jones says he is all too familiar with, a bias in the justice system that has put men like him in a social purgatory that continues to define his life.

“It’s mostly Black men who are affected by this,” he said. “We shouldn’t have to wait seven years after we serve our time to get our lives back.”

[ad_2]

Source link