[ad_1]

About the Archive

This is a digitized version of an article from The Times’s print archive, before the start of online publication in 1996. To preserve these articles as they originally appeared, The Times does not alter, edit or update them.

Occasionally the digitization process introduces transcription errors or other problems. Please send reports of such problems to [email protected].

The IN HER DREAM, THERE was a steel-gray casket in her living room. Who was the dead man laid out in a gray suit? She couldn’t tell. And every time she moved closer to the coffin, someone she didn’t know said, ”You don’t need to see this.” But Beulah Mae Donald knew that she did, and so she woke from her dream at two in the morning in Mobile, Ala., on March 21, 1981. The first thing she did, she later said, was to look in the other bedroom, where her youngest child slept. Michael, 19, wasn’t there. She telephoned one of her six other children. Though Michael had watched television with his cousins earlier in the evening, he had left before midnight.

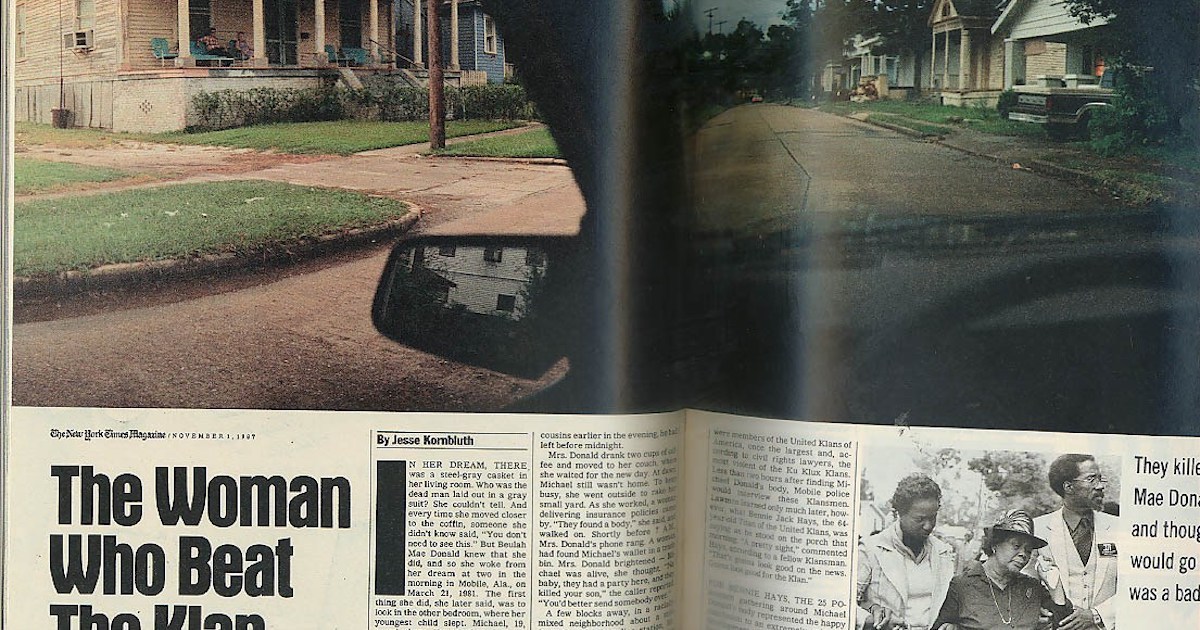

Mrs. Donald drank two cups of coffee and moved to her couch, where she waited for the new day. At dawn, Michael still wasn’t home. To keep busy, she went outside to rake her small yard. As she worked, a woman delivering insurance policies came by. ”They found a body,” she said, and walked on. Shortly before 7 A.M., Mrs. Donald’s phone rang. A woman had found Michael’s wallet in a trash bin. Mrs. Donald brightened – Michael was alive, she thought. ”No, baby, they had a party here, and they killed your son,” the caller reported. ”You’d better send somebody over.” A few blocks away, in a racially mixed neighborhood about a mile from the Mobile police station, Michael Donald’s body was still hanging from a tree. Around his neck was a perfectly tied noose with 13 loops. On a front porch across the street, watching police gather evidence, were members of the United Klans of America, once the largest and, according to civil rights lawyers, the most violent of the Ku Klux Klans. Less than two hours after finding Michael Donald’s body, Mobile police would interview these Klansmen. Lawmen learned only much later, however, what Bennie Jack Hays, the 64-year-old Titan of the United Klans, was saying as he stood on the porch that morning. ”A pretty sight,” commented Hays, according to a fellow Klansman. ”That’s gonna look good on the news. Gonna look good for the Klan.”

FOR BENNIE HAYS, THE 25 PO-licemen gathering around Michael Donald’s body represented the happy conclusion to an extremely unhappy development. That week, a jury had been struggling to reach a verdict in the case of a black man accused of murdering a white policeman. The killing had occurred in Birmingham, but the trial had been moved to Mobile. To Hays – the second-highest Klan official in Alabama – and his fellow members of Unit 900 of the United Klans, the presence of blacks on the jury meant that a guilty man would go free. According to Klansmen who attended the unit’s weekly meeting, Hays had said that Wednesday, ”If a black man can get away with killing a white man, we ought to be able to get away with killing a black man.”

[ad_2]

Source link