[ad_1]

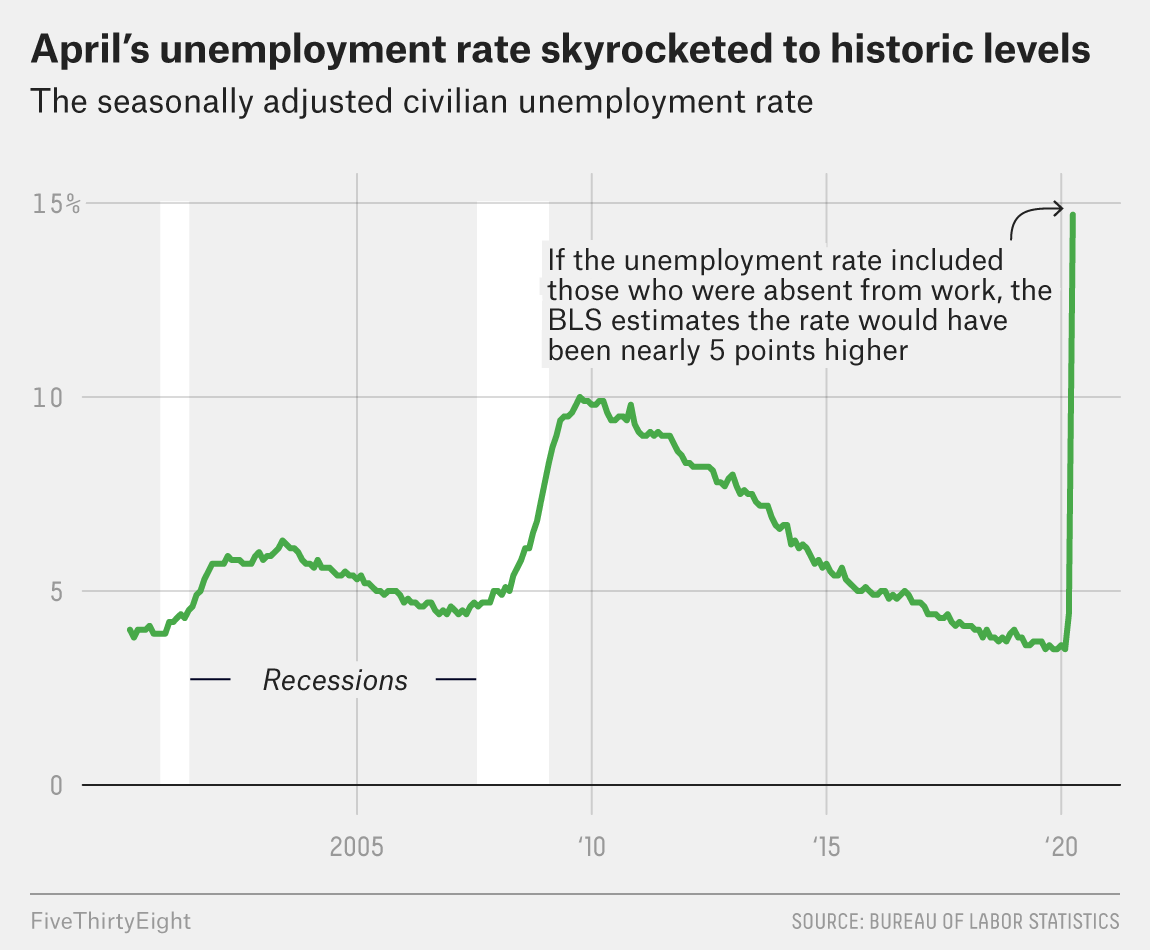

Remember last month, when the jobs report was bad but not apocalyptic? Those were the days. The most recent jobs report is a stunning picture of how the pandemic has reshaped the country’s labor market. Overall, 20.5 million fewer people were employed last month than in March. And the unemployment rate has skyrocketed to 14.7 percent — by far the worst we’ve seen in more than seven decades of economic data.

But the speed of the crisis also means that these numbers are already out of date. The jobs report is based on surveys of businesses and households taken during the middle of April, but the economic situation likely worsened as the month went on. And key metrics, like the unemployment rate, aren’t capturing all the people who are actually out of work right now. According to this month’s report, millions of workers were counted as employed even though they were absent from work for an unspecified reason — and if they had been counted as unemployed on a temporary layoff, the unemployment rate would have been 5 percentage points higher. In other words, as catastrophic as this report might seem, it almost certainly understates the pandemic’s full economic devastation.

To be clear, that’s not the fault of the researchers at the Bureau of Labor Statistics who put the report together. Our economic data just wasn’t designed for a moment where entire sectors of the economy shut down pretty much overnight, leaving millions of people without jobs. “I think of our economic indicators as being a kind of a finely tuned speedometer that says, ‘Are we a little over the speed limit or a little under?’” said Matt McDonald, a partner at the consulting firm Hamilton Place Strategies who writes a monthly analysis of the jobs report. “And right now it’s like we just pulled the emergency brake on the highway.”

That doesn’t mean the report is useless or wrong. But making sense of the numbers — and what they mean for our ability to recover from this mess — is going to take a little more work than usual. Here’s what to bear in mind as you read coverage of the jobs report (or dive into the nitty-gritty yourself) that can help you understand just how bad these numbers are, and what they mean for how the recession could play out.

Headline numbers may understate the damage

This month, there are good reasons to dig deeper into the report. There’s always a significant amount of uncertainty in one of the topline numbers — the 20.5 million jobs that were lost — but the scale of the damage this month means that this month’s estimate could be off by tens or even hundreds of thousands of jobs. Take the initial revision for payroll losses in March. Last month, the BLS reported that 701,000 jobs were lost. In this month’s report, though, it’s adjusted that to 870,000. And the April job losses are much, much larger, which means this month’s report could be underestimating the magnitude of the damage by a significant amount.

The one thing we know for sure is that the unemployment rate is historically high. The government has been tracking this number for more than 70 years, and up till now, the peaks were 10.8 percent in 1982 and 10.0 percent in 2009. For context, economic historians estimate that during the Great Depression, the unemployment rate hit a peak of about 25 percent.

The real number may actually be closer to that Great Depression peak, because by this metric, only people without jobs who have been actively looking for one are considered unemployed. In normal times, that’s already a bit of an issue because it means frustrated job seekers who have given up on finding something aren’t counted. Now, the problem is even bigger because so many workers are being encouraged to stay home to combat the coronavirus. Others might not be job-hunting because they believe there’s no work to be had.

“Job search is going to be tough when it’s a public health risk to be in contact with people and whole sectors of the economy is effectively shut down,” said Nick Bunker, a labor economist at the hiring site Indeed. “So lots of people who are out of work are probably not going to be included in the unemployment rate.”

Then there’s the possibility that some people may have been counted as employed even though it might be more accurate to say they’re temporarily out of work. The misclassification may have happened because of the way workers are surveyed — if they say they were absent from work during the entire week that’s referenced in the survey, interviewers follow up and ask why. Usually, the reasons fall into a standard set of buckets — vacation, childcare responsibilities, illness. But the number of workers who said they were absent from work for “other reasons” skyrocketed once the pandemic started, indicating that some people who had actually been furloughed may have misunderstood the question and answered in a way that indicated they were still employed.

This was a problem the BLS ran into in March, and again in April. In March, the researchers estimated that about 1.4 million people may have been misclassified as employed when they were actually temporarily out of work due to the pandemic; this month, it’s a whopping 7.5 million people. According to the BLS, the April unemployment rate would have been almost 5 percentage points higher if these people were included.

To get a clearer picture of just how many people are out of a job, there’s another metric in the report that might be more useful — the share of the adult population who are employed. This number is particularly helpful in recessions, because that’s when more people are likely to become discouraged and stop looking for work. This month, 51.3 percent of the adult population has a job, down from 60 percent in March. That’s also a historic drop — and yet that number may also underestimate the damage because of the people who may have been mistakenly classified as employed.

The damage is widespread

It’s important, too, to look not just at how many people are out of work, but which sectors of the economy have been hit hardest and which are continuing to do well. “There’s a real question about how many industries can weather this moment,” said Martha Gimbel, an economist at Schmidt Futures, a philanthropic initiative. In March, the job losses were overwhelmingly concentrated in the leisure and hospitality industry, which includes bars and restaurants. This month, those industries were hit hardest again: leisure and hospitality lost 7.7 million jobs, a decline of 47 percent.

But the overall job losses were more spread out than they were last month, signaling that the effects of the shutdown are already rippling into other industries. For instance, there were sharp declines in the health care sector, mainly concentrated in dentists’ and private doctors’ offices, many of which were forced to close or lost a significant amount of business due to the pandemic. Retail, professional and business services — including temporary help services and services to businesses and dwellings — and manufacturing also lost hundreds of thousands of jobs.

There were also some noteworthy disparities in who was more likely to be unemployed. The April unemployment rate was highest for Hispanic workers, at 18.9 percent, but black workers (16.7 percent) were also more likely to be unemployed than Asian (14.5 percent) or white (14.2 percent) workers. Racial disparities in the unemployment rate aren’t that unusual — black workers, for example, generally have a higher unemployment rate than other groups. But the unemployment rate for Hispanic workers in particular was historically high, underscoring a running theme of this pandemic: workers of color are disproportionately bearing the brunt of the economic havoc.

Women (15.5 percent) also had a higher unemployment rate than men (13 percent) — which is atypical, since women usually have a lower unemployment rate than men. And in recessions, men are usually the first to feel the impact. But women are more likely to hold jobs in the industries that have been pummeled since the pandemic began, like health care and child care services, which may explain why they’re experiencing more of the job losses this time around.

Gimbel told us she’ll also be looking at the diffusion index, which is a measure that shows how many industries are gaining or losing jobs. That number, she said, can tell us at a glance “how widespread the carnage is.” This month, the diffusion index is 4.8, which is shockingly low, and signals that job losses were extremely widespread across industries. In February, for example, the diffusion index was 53.7.

Another important tidbit that’s not captured in the employment figures but reflects how widespread the damage has been: the number of people who were working part-time because they couldn’t find full-time work or their hours were reduced doubled in April, landing at 10.9 million.

And if you’re interested in trying to figure out how painful the recovery might be, you can learn a lot by looking at the share of people who were temporarily laid off in April, rather than permanently fired. This may be the least catastrophic part of the report. As in March, the vast majority of jobs lost in April were temporary: 18.1 million of the newly unemployed said they had lost their jobs temporarily, while 2.0 million said the loss was permanent. To be clear — in a more normal moment, 2.0 million lost jobs would be an eye-popping number. But the fact that the job losses are mostly temporary is important because it will be much easier for people who have been furloughed to return to work when businesses start to reopen — assuming, of course, that those businesses haven’t shuttered in the meantime.

Read the fine print

The jobs report is based on two surveys: one of businesses, and one of ordinary households. Normally, that’s barely worth remarking on. But this is not an ideal time to be doing surveys of businesses or people. Last month, the call centers where the surveys are conducted were shut down, and in-person follow-up interviews aren’t happening either. That increases the uncertainty around the numbers in ways that BLS researchers explained in a 14-page note that accompanied the jobs report.

Take the response rate. Julie Hatch Maxfield, an associate commissioner at the BLS, told us some variation in the share of participants who respond is normal, particularly because the survey of businesses is sometimes conducted on a more truncated timeline. In April, the response rate for the survey of businesses was actually much higher than it was in March. But the response rate for the survey of households was 70 percent, compared to 73 percent in March. That lower response rate introduces more uncertainty — but it’s hard to know how that uncertainty influenced the data. For example, Gimbel pointed out it’s possible that unemployed people may actually be overrepresented in the household survey, because they have more time to talk with a government interviewer.

Although it’s hard to predict what next month’s jobs report will show, it is likely to offer more detail about how the COVID-19 crisis is affecting Americans economically. A series of questions are being added to next month’s survey of households that will capture how the pandemic has changed our work lives — for instance, whether people are teleworking, or if the crisis has kept them from searching for work. That might not solve all of the problems with the unemployment rate, but it will make the economic picture a little clearer — although probably not more uplifting.

FiveThirtyEight Politics Podcast: COVID-19 broke the jobless claims chart

[ad_2]

Source link