[ad_1]

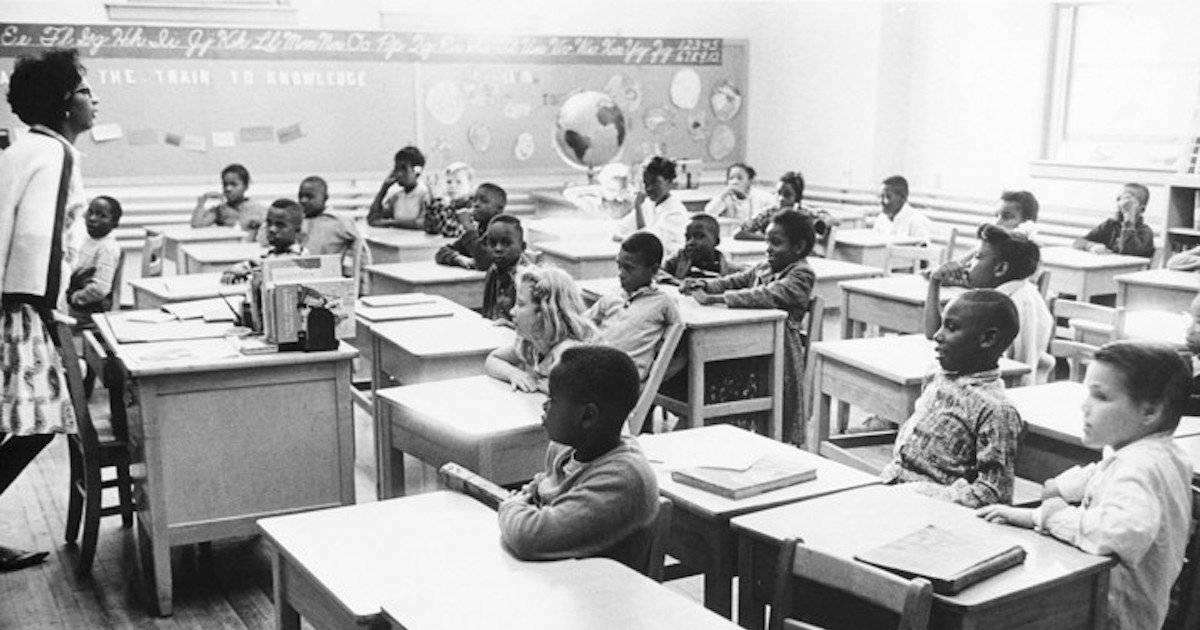

For 25 years, the Emory University professor Vanessa Siddle Walker has studied and written about the segregated schooling of black children. In her latest book, The Lost Education of Horace Tate: Uncovering the Hidden Heroes Who Fought for Justice in Schools, Walker tells the little-known story of how black educators in the South—courageously and covertly—laid the groundwork for 1954’s Brown v. Board of Education and weathered its aftermath.

The tale is told primarily through the life of Horace Tate, an acclaimed Georgia classroom teacher, principal, and one-time executive director of the Georgia Teachers and Education Association (GTEA), an organization for black educators founded in 1878. Later in his career, he became the first African American to earn a Ph.D. from the University of Kentucky; at the time, Georgia still banned black students from state doctoral programs. Walker first met Tate in 2000. Over the course of the next two years, he told her about clandestine meetings among and outreach to influential black educators, lawyers, and community members tracing back to the 1940s. He also revealed black teachers’ secret and skillful organizing to demand equality and justice for African American children in Southern schools. After Tate’s death in 2002 at the age of 80, Walker continued a 15-year exploration, relying on Tate’s extensive archives to expose the full picture of how black educators mounted civil rights battles—in the years preceding and immediately following the Brown decision—to protect the interests of black children.

The resulting account, which features anecdotes about and cites wisdom from prominent black leaders such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and W.E.B. Du Bois, offers an intriguing look at black education and helps inform the ongoing discourse on school desegregation. I recently spoke with Walker about the crucial role black educators played in the evolution of public education in the South. The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

[ad_2]

Source link