[ad_1]

In recent years, artists of color have garnered growing attention for their work, which they have shown—and sold—more and more frequently in the international archipelagos of the most powerful galleries. In 2019 Hauser & Wirth filled their 30,000-square-foot Los Angeles gallery with work by David Hammons, and they signed black art stars like Charles Gaines, Simone Leigh, Henry Taylor, and Amy Sherald. David Zwirner showed Kerry James Marshall in London and began representing Njideka Akunyili Crosby in the United States. After showing LaToya Ruby Frazier and Chris Ofili (who moved to Zwirner) for many years, Gavin Brown brought Frida Orupabo to Rome and Arthur Jafa to the world, via Harlem. This may be the glitziest wave of art world diversification ever. But it is not the first.

The path these influential dealers are taking now was traced in the 2000s by a scrappy gallery in Harlem founded by a young poet/critic: it was known as The Project. An exceptional number of compellingly diverse artists who had New York debuts at The Project have gone on to major careers making work that feels ever more relevant. And the gallery’s own rise and demise tracks the transformation of the art business from a smattering of white cube storefronts to a highly professionalized and securitized constellation of mega-galleries, auctions, and art fairs around the world.

New York critic Christian Haye opened The Project in an unrenovated dance club on West 126th Street in the fall of 1998. The gallery quickly made a reputation by staging the first New York shows for artists such as Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset, Paul Pfeiffer, and Julie Mehretu, as well as important gallery shows of conceptual artist Daniel J. Martinez and performance artist Pope.L. Over its nine years of operation, the gallery also worked with sculptors like Monica Bonvicini, Art Domantay, José Damasceno, Romuald Hazoumè, and Kimsooja, as well as sound artist Stephen Vitiello and painters Kori Newkirk and Peter Rostovsky.

Haye was one of several new, independent, bootstrapped New York gallerists—survivors of the era include Gavin Brown, Jose Freire, Andrew Kreps, and Michele Maccarone—who brought emerging artists from around the world into the dialogue of New York. He saw The Project as a continuation of his critical practice of the 1990s, when he began exploring the racial, cultural, and geographic broadening of contemporary art, writing reviews and features for new European magazines, like the London-based Frieze and Amsterdam-based Dutch. “I basically opened a gallery to show artists I’d been wanting to write about,” Haye told Holland Cotter in a 2000 New York Times profile. In a recent phone conversation, Haye said he saw operating a commercial gallery as criticism by other means, a way to pursue ideas through exhibitions while avoiding the hidden constraints of fundraising and the commercial marginalization of artists, all of which he associated with nonprofit spaces.

In 2000 Haye opened a gallery in downtown Los Angeles, with a solo by Martinez followed by a group exhibition curated by a young Jens Hoffmann. Though multiple spaces are the norm for mega-galleries now, Haye offered a more prosaic reason for opening in LA: the weather. It cost less to fly across the country and put a show together there than it did to heat the Harlem building during a New York winter.

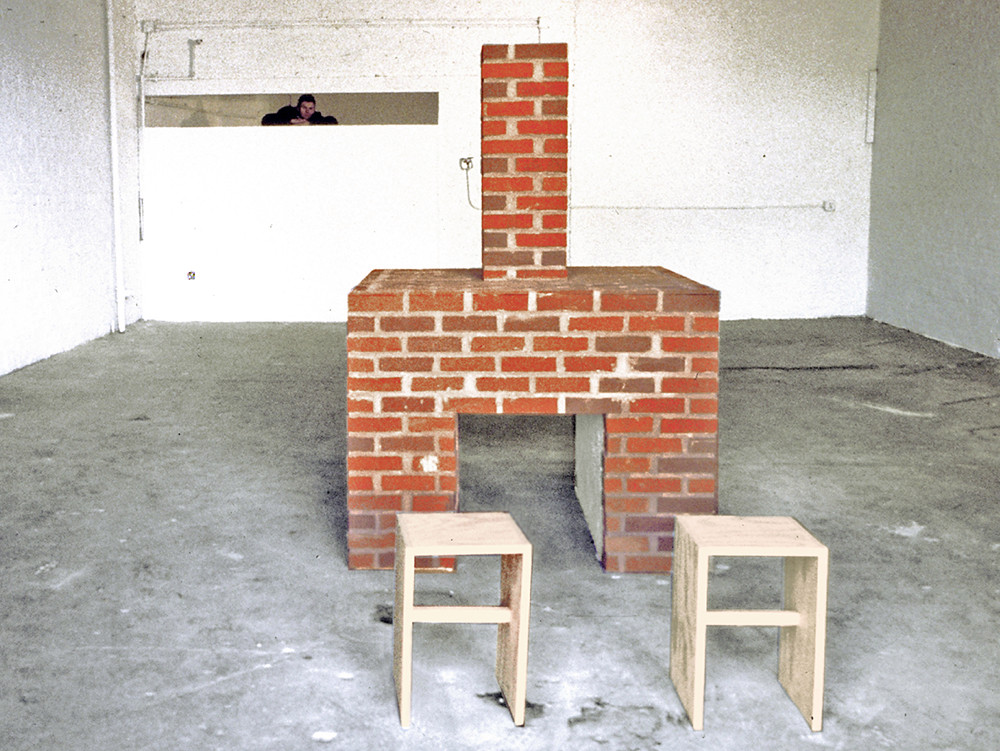

The cold was something I remember clearly from the first show I saw at The Project, the US debut of Elmgreen & Dragset in February 1999. A sculpture—a functional fireplace of salvaged brick flanked by scrap-wood stools—stood in the center of the walled-off ground floor gallery, which could be glimpsed by climbing steps set up in the back office and peering over the temporary plywood partition. The only way to actually enter the main space was through a large hole in the brick wall at the back of the building. The show continued in the dank basement, where the artists projected an image of the full moon on the wall, which reflected in a small, square plexiglass pool on the floor. It was fantastically underproduced, abject and sublime. I remember how the gallery’s raw atmosphere only heightened the sense of miraculous discovery. What I’d forgotten is how Haye and his artists had anticipated just such a reaction from white gallerygoers who imagined themselves bold for venturing uptown. In a recent email exchange, Michael Elmgreen recalled the fireplace as an offer of warmth and shelter to homeless men in the neighborhood. To visitors from downtown, who might otherwise dash from a waiting car service to the gallery’s front door, it was also a challenge, daring them to walk around the corner on the streets of ungentrified Harlem.

After the Elmgreen & Dragset exhibition, I returned to the Project many times. Exhibitions by Hazoumè and Mehretu were among the most memorable. Shown in the summer of 1999, Hazoumè’s masklike sculptures felt simultaneously of the place they were made–on the sidewalks and vacant lots surrounding the gallery–and of the artist’s home in Benin. (Hazoumè’s second New York show was in 2018, at Gagosian. A globe-spanning career of major exhibitions transpired between them.) Mehretu’s stunning, gaze-filling paintings were already garnering attention in New York even before their first appearance at The Project in 2000. Their ambitious scale and Mehretu’s intricate drawing and painting process meant that collector demand immediately outstripped possible supply, a good problem that would eventually become a bad one.

While collectors clamored for Mehretu’s paintings and Pfeiffer’s transfixing video works, the gallery and its artists generated buzz among curators. Multiple gallery artists were included in MoMA PS1’s Greater New York surveys in both 2000 and 2005, and in Whitney Biennials beginning in 2000, the year Pfeiffer also won the Whitney’s inaugural $100,000 Bucksbaum Prize.

In 2003, as the rest of New York’s gallery scene settled into Chelsea garages, The Project moved to West 57th Street. The frisson of basement discoveries in Harlem was replaced by the incongruity of videos of Pope L.’s street performances in a pristine, third-floor white cube gallery near Bergdorf Goodman. In September 2004, Martinez filled The Project’s main gallery with The House America Built, a full-size replica of the cabin that Ted Kaczynski, aka the Unabomber, built in Montana, which was in turn modeled after Thoreau’s cabin at Walden Pond. Martinez split the cabin in two, à la Gordon Matta-Clark, and painted it in colors from the latest Martha Stewart Paint Collection. (Stewart had just been convicted of insider trading, and she entered a federal prison in West Virginia to begin serving a five-month sentence the week after Martinez’s show closed. Stewart’s stock trading came to light in 2003 when her tipster, a biotech CEO named Sam Waksal, was among those caught up in an art market sales tax investigation; he was charged with evading sales tax on $12 million worth of purchases from Larry Gagosian.)

Then as now, a dealer of emerging art often relied on the sales of breakout stars to cover the expenses associated with showing the rest of his program. For The Project, that was Pfeiffer and Mehretu. Haye also turned to his collector clients for funding. He borrowed five- and six-figure sums and gave his creditors discounts of up to 30 percent on purchases; Miami real estate developer Dennis Scholl called them “friendly loans,” as quoted by Christopher Mason in a 2005 article on the emerging phenomenon of gallery waitlists. Sometimes these friendly loans also included a promise of first pick of an artist’s work.

When one creditor/collector with such a right-of-first-refusal agreement saw Mehretu paintings he had hoped to buy hanging in a museum with the names of other collectors listed as owners on the wall text (in one case, the owner was the Museum of Modern Art), he sued Haye and The Project for breach of contract. Records revealed in the 2005 lawsuit showed Haye had made similar first-choice agreements with at least five clients. A judge found in favor of the collector, awarding him $1.7 million, the difference between the sales price of eight Mehretu paintings he said he would have bought and their estimated value in 2005. Before Haye settled with the collector—presumably some artworks changed hands—he closed The Project and opened a new gallery called Projectile, with the same roster of artists and in the same 57th Street space. Projectile’s first show was new work by Mehretu. In Los Angeles Haye gave up his downtown gallery, and opened a new project (sic) space in Culver City in collaboration with Maccarone. It operated for two years.

Business went on at (The) Project(ile). In 2006 Mehretu’s work was included in a group show across the street at Marian Goodman; Goodman had been a quiet but steady supporter of Haye and his program. Martinez’s Divine Violence (2007), an installation of 125 panels painted with automotive gold flake and inscribed with the names of organizations that espouse violence, filled the entire gallery. Then it went to the Whitney Biennial, and was acquired by the museum. Shifts in the art world and the proliferation of expensive art fairs, along with the 2008 financial crisis, brought The Project to an end.

When discussing The Project recently, Haye reflected on the dueling roles of the gallerist and the dealer, and the challenges of balancing curatorial daring and dealmaking. He also noted the problems of an art world oriented around the tastes and desires of billionaire collectors and the institutions they fund. “I recognized I can’t ask questions about these power structures without including myself in it,” Haye said in a recent interview. These observations feel familiar, if not perennial. When asked about the notable diversity of his program, Haye rejected the idea that he’d just been a black dealer showing black artists when, he said, only a third of the artists he showed were people of color. No other major gallery has yet been able to match that program. At The Project, a young black poet-turned-critic opened two galleries on a shoestring and had an immediate impact, introducing powerful works by an extraordinary group of artists. It felt like the future, and in some ways, at least, it was. In other ways, it feels like a long-lost past.

[ad_2]

Source link