February 25, 2024

Curator Denise Muller revisits a major movement in American art and history for what may be the most celebrated exhibition the institution has seen

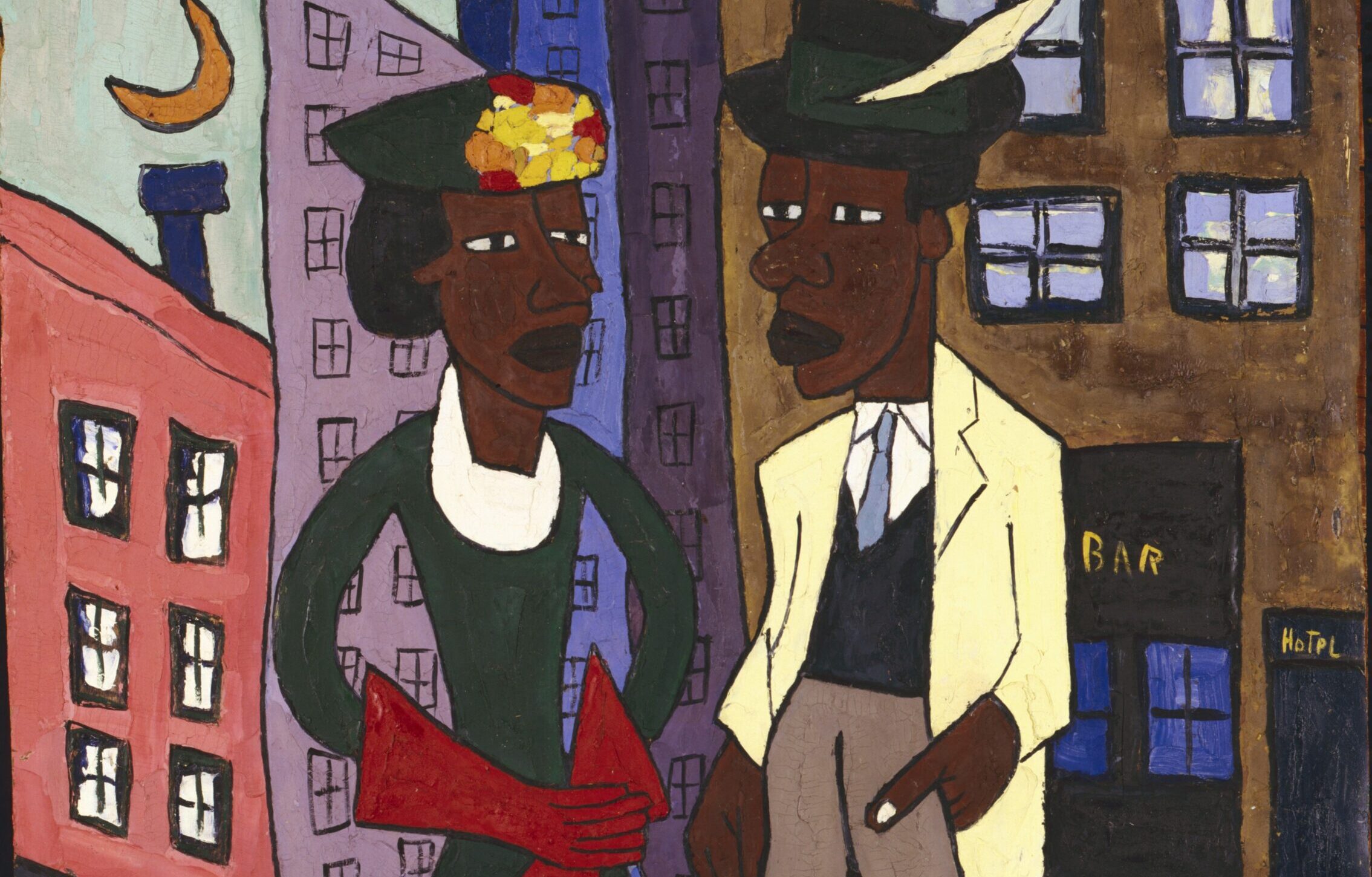

The Metropolitan Museum of Art revisits a major movement in American history and art with one of the most celebrated exhibitions the institution has seen. It has been 55 years since the Met showed, Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900—1968, an Exhibition on the Harlem Renaissance era, without a lick of Black art. This time around, on Feb. 25, with the help of the Ford Foundation, the Barrie A. and Deedee Wigmore Foundation, and Denise Littlefield Sobel, the Met redeems itself with The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism, curated by Denise Murrell, Merryl H. and James S. Tisch Curator at Large.

“This landmark exhibition celebrates the brilliant and talented artists behind the groundbreaking cultural movement we now know as the Harlem Renaissance,” Ford Foundation president Darren Walker said in a press statement.

“I thank the dedicated team at The Met and applaud Denise Murrell for her vision and thoughtful curation of this vibrant collection of paintings, sculptures, film, and photography that gives a powerful glimpse into the Black experience in the early 20th century.”

The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism is both an ode to philosopher Alain Locke and a reconstruction of his rejection of stereotypical Blackness that white America clung to in favor of the amplication of Black art and excellence and complexity—that is—Locke’s concept around The New Negro Renaissance. Akin to Locke, Murrell is interested in reviving “autonomous Black self expression” of the time. The show negotiates this concept with 160 works, including James Van Der Zee, Aaron Douglas, James Weldon Johnson, Charles S. Johnson, Langston Hughes and not-so-well known artist Laura Wheeler Waring.

BLACK ENTERPRISE caught up with Murrell to discuss her curation and Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism. Aptly so, the show begins with portraiture of thinkers who were in conversation with one another and Locke’s philosophy — in particular — a portrait of Zora Neal Hurston, Murrell told BE.

“She’s not only a varied literature writer, the portrait is by Aaron Douglas, who is not only one of the leading Harlem Renaissance artists and the loan of that portrait is from Fisk University. So, we wanted to stress the importance of loans from historical Black colleges and universities.”

BLACK ENTERPRISE: Talk about your decision to include non-African Americans in this show about Black art and expression?

Denise Murrell: [Alain Locke] was open to the idea that the movement should be African American lead, but it was never exclusively African American. There were also West African Caribbean writers and artists and dancers and performers who were part of this … He believed that if an artist like Picasso was working with African aesthetics and was making modern, non stereotypical portrayals of a Black French person, or a Black Dutch person, or a Black British, then they’re all part of the same [movement]. As a curator trying to reconstruct the history to the extent that I have white European artist in the show, almost all of them were named by a Alain Locke as European artist who he thought were worthy of admiration because they were doing the same thing in Europe making modern, dignified, portrayals of Black European subjects.

Harlem Renaissance history is epic in proportion. The same goes for its art history. How were you able to narrow down the artists who would be exhibited?

It was a challenge, of course. I had very authoritative guidance. I had an advisory committee that included Mary Schmidt Campbell, who was the former president of Spelman College, but before that, she was director of the Studio Museum in Harlem and she was the curator of the Studio Museum show in 1987, which is the last New York City Museum show about the Harlem Renaissance. Then there were other scholars, Rick Powell, Bridget Cook, Emilie Boone as well as various European scholars of Black Europe … and some of the period publications—looking at covers of Crisis, NAACP and Urban League’s publication, Harmon Foundation and HBCU’s.

Many are not familiar with the work of Laura Wheeler Waring. What about this work earned your favor?

The most compelling thing was her work. I had come across a couple of portraits that were in the Smithsonian collection. I did a show five years ago at Columbia, at Columbia’s Art gallery and I have [Waring portraits] on view. A family member, Roberta Graves came to see that show [Waring] is her great aunt. I happened to be in the galleries and we met. [Roberta] had a whole portfolio of images of Laura Wheeler Waring — over 30 portraits that were in her private family collection, and her cousin Madeline Murphy Rabb also had portraits. Most of these portraits had never been published before. Some of them had not even been dated or named.

As an art historian, you’re always intrigued by this body of work that’s overlooked. I accepted [Roberta’s] invitation to come see these paintings in person, and I was just astounded and amazed at the virtuosity, her style, her capability to render Black people — mostly Black women — from all walks of life. I just felt the beauty and the dignity and the artistic virtuosity that I saw in these portraits that no one else had seen before merited bringing a half dozen of them into the exhibition.

Who is this show for? Is this show accessible?

It is for everyone. We want as many people as possible to see the show. We want a diverse audience. We want to bring in younger generations. We want to reintroduce this material. We’re hosting lots of student groups from HBCUs to all public universities in New York City and the high schools and even junior high schools.

We want the art world to come and see this and to think about why the Harlem Renaissance is never heard of outside of the course on African American art when it should be part of the central narrative of American art history and of international modern art history. We want to have this material available for inclusion in future narratives about the history of art. We want to see the way that we as an American culture define ourselves as an American. Culture that includes these Black voices, who were central in that period, the 1920s through the forties.

How does it feel to be Black and woman and purveyor of this body of work?

Right now, I feel a real sense of elation, even exhilaration and also a sense of relief that we actually got this done at the level that we did get it done. I’ve been wanting to do the Harlem Renaissance show since I finished my PhD at Columbia. I had some mention of the Harlem Renaissance when I had a whole section on it in my 2018 exhibition at Columbia, I feel very gratified that the Met gave me a base for doing that and gave me absolutely the top level resources and talent and expertise for the design of the show.

I feel gratitude as well. I’m just appreciative. It has taken a village. Within the broader art world, the advisers, the 11 members of the advisory committee, as well as all of the museums, who gave us loans, the museums and the private collectors, colleagues, supporters and the donors who funded The Ford Foundation, Denise Sobel and so many others, all of this was absolutely necessary to get the show done. I’m just really appreciative of all of that. I feel excited about the prospect that it will draw a large and diverse audience.

Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism opens in New York City at The Metropolitan Museum of Art on Feb. 25 and runs through July 28, 2024. The exhibition can be viewed on the museum website and social media. For more information and additional programming, check out the Met online.

RELATED CONTENT: Why Investing in Black Women’s Art is a Power Move

Enter your Email Address below to get our fun-filled Newsletter!

© 2024 Black Enterprise. All Rights Reserved.