[ad_1]

In 1889, the year of his death, Vincent van Gogh wrote a letter to his brother Theo. “They say—and I am willing to believe it—that it is difficult to know yourself—but it isn’t easy to paint yourself either,” van Gogh wrote. To know oneself fully through that creative process had been a lifelong goal for the great Post-Impressionist. Over his career, he created 30 self-portraits which, when arranged in chronological order, act as visual autobiography. He was hardly alone in his pursuit of truth through self-portraiture, and he is not the only artist to have done so. And sometimes, self-portraits created during the final stages of a career can prove to be the most truthful images of artists. Below are just a few of those famous works.

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Portrait at the Age of 63 (1669)

Over a 40-year period, Rembrandt, the great painter, printer, and draftsman of the Dutch Golden Age who achieved commercial success because of his exceptional depiction of light, produced dozens of self-portraits. These works track both his emotional and technical maturity. His first important self-portrait, Rembrandt Laughing (1628), was painted in a subdued, limited palette with short brushstrokes. This self-portrait, among his last ones, evidences a much more technically savvy artist—the edges of his figure are noticeably crisper—interested in the impact of time one one’s psychology. Here, he stares somberly at the viewer, looking visibly weathered.

Gianni Dagli Orti/Shutterstock

Frida Kahlo, The Broken Column (1944)

Frida Kahlo was struck by a trolley car early in life, leading to lifelong suffering and injury, which became inextricable to her self-perception and presentation. “I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best,” she said. She underwent numerous spinal surgeries throughout her life, and often painted her image while bedridden recuperating. During the creation of The Broken Column, Kahlo was encased in a metal corset that provided support for her back, which she incorporated into her self-portrait. In it, she stands alone in a desolate landscape, the corset acting as the sole glue for her bisected torso. Though tears stream down her face, she stares, as always, boldly at the viewer. In place of a spine is the painting’s titular fractured column.

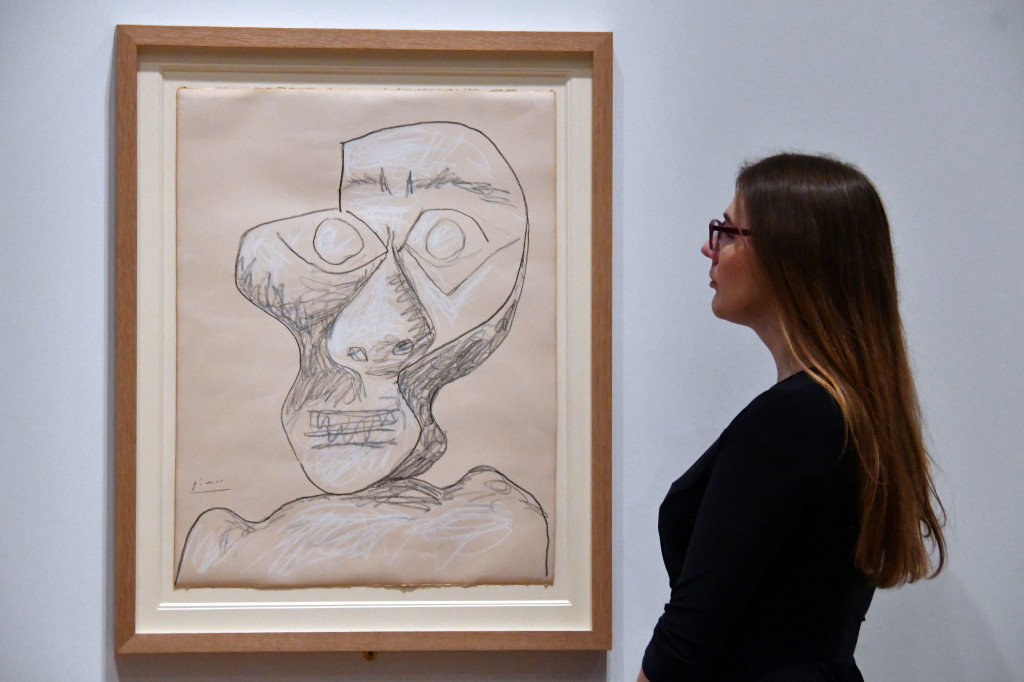

Nils Jorgensen/Shutterstock

Pablo Picasso, Self-portrait (1972)

Picasso painted up to the hours before his death at 91, and the years prior were marked by his prolific output. Self-portrait Facing Death, a crayon drawing on paper, was completed over several months and remains among the most famous works produced in his late career. According to Picasso’s friend Pierre Daix, during a visit to his studio, Picasso “held the drawing beside his face to show that the expression of fear was a contrivance,” adding that upon returning to Picasso’s studio months later he saw that the drawing had gained even coarser lines. “He did not blink,” Daix wrote. “I had the sudden impression that he was staring his own death in the face, like a good Spaniard.” The final version of the artwork, titled Self-portrait Facing Death, resembles a mask of pure anxiety, drawn in seasick green and milky pink. The subject’s wide-eyed gaze stares through the viewer, conveying little acceptance of his impending death.

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Sofonisba Anguissola, Self-Portrait (1610)

The 16th-century Italian painter Sofonisba Anguissola is among the female Old Masters whose work has recently enjoyed long-overdue commercial and academic interest. Her sensitive, precise portraits were celebrated last year in a joint exhibition with fellow Italian master Lavinia Fontana at the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid. Anguissola painted self-portraits well into old age, and in these latter paintings, the viewer can appreciate the artist’s austere gaze, which contrasts with her sumptuously colored and loose depictions of other sitters.

Francisco Goya, Self-portrait with Dr. Arrieta (1820)

The oil painting Self-portrait with Dr. Arrieta, or Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes, was among the last of Goya’s many self-portraits. In 1819, the Spanish painter was struck by sudden illness; years prior, he had fallen similarly ill with partial deafness, dizziness, and delirium, among more ailments, and the diagnosis of both sick bouts has been the subject of much historical investigation. Some look to his doctor, Eugenio García Arrieta, for the answers, as he was a well-known plague specialist in Spain, which was regularly swept by epidemics. Goya obviously survived his illness and painted the work pictured above as homage to the doctor’s services. It features the artist weakened in bed, grasping his bedsheets as he collapses into Arrieta’s arms. Shadowed onlookers crowd the duo, who are illuminated in a bright, hopeful palette. It bears the inscription, “Goya, in gratitude to his friend Arrieta: for the compassion and care with which he saved his life during the acute and dangerous illness he suffered towards the end of the year 1819 in his seventy-third year.”

Boris Roessler/EPA/Shutterstock

Edvard Munch, Self-Portrait. Between the Clock and the Bed (1940–43)

Edvard Munch was not known as a happy man. “My fear of life is necessary to me, as is my illness,” the Norwegian artist once wrote. “Without anxiety and illness, I am a ship without a rudder…. My sufferings are part of myself and my art.” He attained fame early in his career through his startling depictions of distress and isolation, most famously with The Scream (1893). Munch retreated increasingly inward later in life and lived his last 27 years alone in his home outside Oslo, where authorities discovered thousands of artworks after his death in 1944. Among the trove was Self-Portrait. Between the Clock and the Bed, in which he depicts himself as lonely and stiff, with cavernous eyes that contrast with the bright colors of a bed and clock, symbols of his mortality. Behind him, an open door waits beside his famous works.

Armando Babani/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

Pierre Bonnard, Self-portrait in a mirror (1930)

Even as he was nearing death, the artworks of Pierre Bonnard, a founding member of the French Nabi movement, remained dedicated to bright, decorative palettes. Still, in spite of the bright colors, his paintings did not shy away from themes related to death. Unlike in his self-portraits completed as a young man, which features the artist well-illuminated and facing forward, the aged Bonnard is depicted as shadowed and gaunt. He avoids eye contact with viewer, often twisting his body away. His eyes lack definition; in place of pupils are twin black holes. In the mirror, one hand is in view, grasping his shirt, as if the viewer has interrupted Bonnard in the midst of painting this portrait.

Nils Jorgensen/Shutterstock

Lucian Freud, Self Portrait (2002)

“I don’t want to retire,” the British painter and draughtsman Lucian Freud once said. “I want to paint myself to death.” For the most part, he got his wish. He painted almost up to the week of his death in 2011. He was best-known for his somber figurative art, and in his final years, he repeatedly turned to himself as subject, most famously examining the effects of time on his body in the full-length nude Painter Working, Reflection (1993). In this 2002 self-portrait, the psychological weight of death bears down on him. He tugs, discomforted, on his tie. His weary expression is framed by gray, frenzied brushstrokes.

Peter Dejong/AP/Shutterstock

Vincent van Gogh, The Oslo Self-Portrait (1889)

Van Gogh’s self-portraits are among the most recognizable artworks in the world. He often struggled to afford a model and was forced to use his own reflection to practice painting. Around 25 self-portraits were completed in Paris between 1886 and 1888, and he described the last made during that period, a year before his suicide, as “quite unkempt and sad…something like, say, the face of—death.” He painted the work featured here while institutionalized in a sanitarium in Saint-Rémy for psychosis and depression. Like many of his self-portraits, he depicts himself restrained and viewed from a three-quarters perspective. He watches the viewer from the side, as if unable to face forward. In a letter written during his stay, he describes the painting as “an attempt from when I was ill.”

[ad_2]

Source link