[ad_1]

In the late 1970s, two very different horror movies redefined the proliferating genre’s norms. In 2018, updated renditions of the same movies are doing it all over again, at a time when horror is enjoying a renewed cultural footprint.

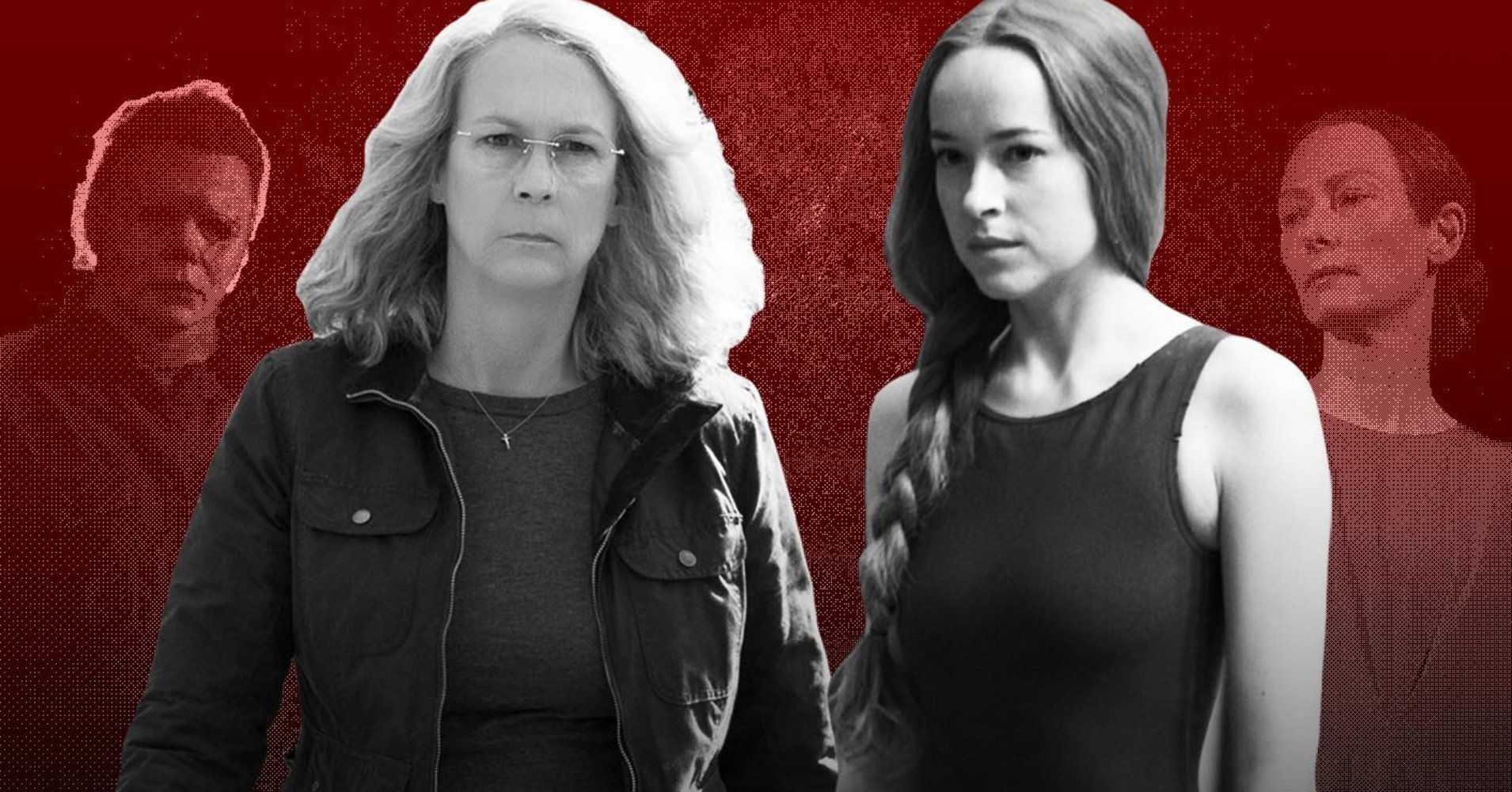

The new “Halloween” and “Suspiria” open a week apart in October, with the former generating totally insane profits and the latter introducing an eminent cult classic to fresh audiences. But what makes the pair unusual is how deep their connections run, from the films’ chummy directors and correlating scores to the ways the treasured tales are now being modernized.

When “Suspiria” and “Halloween” were first released, they elevated burgeoning subgenres and vaulted their respective directors into Hollywood’s underground A-list, despite the fact that each was produced without a large budget or the backing of a major studio. The Italian maestro Dario Argento, drawing inspiration from Thomas De Quincy’s opium-aroused essay series “Suspiria de Profundis,” placed 1977′s “Suspiria” within the pulpy trend known as giallo, a baroque tradition that melded slasher tropes, supernatural terrors, erotic exploitation and mystery elements. (Today, “Suspiria” is arguably the definitive giallo paragon.)

With “Halloween” one year later, John Carpenter landed his own magnum opus and popularized serial-killer escapades ― first initiated via “Psycho” and “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre” but crystallized with “Halloween,” which would go on to spawn countless copycats and remain the most celebrated hack-and-slash until “Scream” almost 20 years later.

Archive Photos via Getty Images

Both movies revolve around young women thrust into waking nightmares in what should be safe spaces: The original “Suspiria” finds a Snow White-esque Jessica Harper fleeing a renowned German dance academy that turns out to be run by a wealthy witches’ cult; “Halloween” has a suburb-dwelling Jamie Lee Curtis evading the masked murderer Michael Myers while babysitting her neighbors’ kids. The heroines survive, but otherworldly evils render them victims nonetheless.

Argento and Carpenter became friends and mutual admirers after their films debuted, citing each other’s work as influences. “I thought it was just wonderful,” Carpenter told me earlier this month when I asked him about “Suspiria,” known for its hallucinatory color scheme. “I thought the style [and] everything about it was just fabulous.”

Coincidentally, Luca Guadagnino (“Call Me by Your Name”) and David Gordon Green (“Pineapple Express”), the respective directors responsible for this year’s “Halloween” sequel and “Suspiria” reimagining, are also pals. In fact, Green was slated to direct “Suspiria” before Guadagnino took over. They developed the project together in 2013, and Green wrote an early draft of the script after spending time at Guadagnino’s house near Milan.

“It was a big-budget horror movie at a time when the ‘Paranormal Activity’ movies and other micro found-footage movies were defining horror,” Green told me of his “Suspiria” efforts. “Nobody wanted to make my $20 million elegant opera of a horror film. So that went, and then Luca decided to do it himself.”

Guadagnino, who fell in love with Argento’s “Suspiria” (as well as Carpenter’s sci-fi romance “Starman”) as a teenager, was set to produce Green’s interpretation, which he’s said would have diverged from the version he eventually directed himself. “I love David,” he told ComingSoon.Net. “I am a big fan and I am so proud that we have our two horror movies out more or less in the same week, so it’s fantastic.”

Reporters Associati & Archivi via Getty Images

Like that of Argento and Carpenter, Guadagnino and Green’s unlikely camaraderie extends a “Suspiria”-“Halloween” legacy that’s as profound as it is over-mythologized. Part of that lore revolves around the films’ haunting music, often imitated but rarely topped. Various articles over the years have claimed that, when composing the “Halloween” score, Carpenter took cues from the symphonic “Suspiria” melodies, written and performed by prog-rock band Goblin.

“Sure, I loved that stuff,” the ever-nonchalant director told Dazed in 2017 when asked whether Goblin influenced him. “It’s really neat [the way Argento uses music.] And he’s a totally underrated filmmaker, I think.”

But in our interview, Carpenter denied the linkage altogether, saying it’s merely the stuff of legend. “It really wasn’t that big an inspiration, I have to admit,” he said. Before offering a definitive rebuttal, Carpenter continued, laughing: “Actually, I won’t say it wasn’t, just because I want to continue to be associated with it.”

Instead, Carpenter said, his score stemmed from the bongo drum tutorials he’d received from his father. Using a 5/4 time signature, he banged out a rapid-paced tempo that electrified his brilliantly sleepy chase sequences. Even if it’s indirect, however, some “Halloween” hymns do bear a passing resemblance to the pulsating hypnosis heard in “Suspiria,” which at times conjures the minor-key classic “Tubular Bells,” whose discordant timbre became a perfect anthem for 1973′s “The Exorcist.”

Just as Carpenter’s “Halloween” tunes announce Michael Myers’ presence before the villain is seen, Argento, who contributed to the Goblin album, aimed to conjure an occult ambiance before it’s ever revealed that the dance school’s imperious headmistresses are casting spells. “I need music that always lets the audiences feel that witches are there, even if there is nothing on the screen,” he instructed the band, according to keyboardist Claudio Simonetti.

In the new “Halloween” sequel, which expunges the franchise’s 10 intervening installments, Carpenter and Green toy with the scores’ perceived similarities. (Yes, Carpenter returned to help compose the contemporary film’s music and serve as a creative consultant.) In rejiggering 1978′s prototype, Carpenter wrote “The Shape Hunts Allyson,” a track whose lullabying synthesizer and throbbing drum pulse echoes the “Suspiria” theme. Appearing around the soundtrack’s halfway mark, it underscores his and Green’s kinship with the giallo fantasia they’ve long revered.

Stylistically and thematically, Green and Guadagnino also overhaul their predecessors’ vintage gender dynamics. Since the ’70s, “Suspiria” and “Halloween” have found detractors who challenge the former’s misogynistic bloodshed and the latter’s ostensibly conservative choice to kill off sexually active teen girls. The 2018 versions rewrite Argento’s and Carpenter’s unintended wrongs.

Green and Guadagnino have reveled in their films’ female-centered craftsmanship. “I think I’ve quietly made a very feminist horror movie. I mean, it’s three female leads kicking ass and getting rocked,” Green proclaimed. Guadagnino has said “Suspiria” is “soaked in the ideas of feminist art,” including that of Gina Pane, Francesca Woodman, Judy Chicago and Ana Mendieta.

In practice, of course, “Halloween” and “Suspiria” feel far different from each other. Green’s is a full-throttle crowd-pleaser, and Guadagnino’s a meditative slow-burn ― an inverse from their predecessors. Furthermore, this “Suspiria” score, composed by Radiohead frontman Thom Yorke, sounds nothing like Goblin’s maximalist synth roar. It sounds like, well, Thom Yorke, he of eerie laments.

Guadagnino, a fellow Italian who also sets his “Suspiria” in 1977, trades Argento’s phantasmagoric hues and thin plotting for a gray palette rich with psychological nuance. Susie Bannion, the repressed Ohio-born protagonist portrayed by Dakota Johnson, arrives in a politically fraught Berlin without the same resistance to witchcraft that plagued Harper’s character. As Susie succumbs to a well-robed Tilda Swinton’s matriarchal incantations, a more explicitly feminist (and gruesome) narrative rises to the surface ― one that exalts the vigor of feminine convergence without shying away from the brutality it sometimes yields. It’s a story about motherhood, trauma and the quest for power, told through dance, an art form adept at marrying sensuality and violence. Victimhood is not on the table. She won’t torch the building and run.

Universal Pictures

Green’s calling was less about rectifying Carpenter’s transgressions than it was those of the many writers and directors who took over in Carpenter’s absence. (Until now, Carpenter has barely touched a “Halloween” entry since co-writing 1981′s “Halloween II.”) The franchise redrafted the fate of Curtis’ defining lead, Laurie Strode, many times over. She’d died offscreen by 1988′s “Halloween 4: The Return of Michael Myers” but was resuscitated and presented as a traumatized underdog in hiding in 1998′s “Halloween: H20.” Michael ultimately prevailed in 2002′s “Halloween: Resurrection,” killing Laurie after she promised to reencounter him in hell. In other words, she never got the triumph she deserved, letting us instead root for Michael in typical slasher-flick custom.

The new “Halloween” gives her that triumph. By the end, it’s more her fable than it is Michael’s.

Forty years after the sociopath stalked Haddonfield, Laurie is holed up as a doomsday prepper ― but not the kind of naïve waif who’s long populated horror (Mia Farrow in “Rosemary’s Baby” and Judith O’Dea in “Night of the Living Dead,” for example). Her paranoia has splintered Laurie’s relationship with her only daughter (Judy Greer), rendering “Halloween” another chiller about motherhood and PTSD. Rightfully convinced Michael will return, Laurie is armed physically and emotionally, ready to combat the boogeyman who has caused her so much grief. Like Susie in the current “Suspiria,” she is not about to turn her back on the horrors surrounding her. Even with wildly different outcomes, both movies result in confrontations and revelations. The malefactors who produce their inciting dread are usurped.

Amazon Studios

But softer corollaries emerge, too, even if they’re unintended. The most unnerving “Suspiria” scene, in which Susie’s dance movements possess a recreant student’s limbs so they crack and contort in abnormal shapes, somewhat mirrors a conceit posited in “The Eyes of Laura Mars,” the 1978 giallo-light thriller conceptualized and co-written by Carpenter. “Mars” centers on an edgy photographer (Faye Dunaway) who becomes viscerally linked to a serial killer and experiences his crimes as he commits them ― much in the way that Sus’s choreography manipulates her classmate in real time. It’s a demented sort of catharsis, the kind that only the darkest and most disturbing films can achieve. If closure marked the initial “Suspiria,” disconcertedness torments its remix.

As “Halloween” and “Suspiria” continue a year filled with socially fertile horror titles (see also: “A Quiet Place,” “Hereditary,” “The Little Stranger”), the parallels between the genre’s 1970s heyday and today’s renaissance grow denser. It makes sense: Both decades are thorny, moody eras in the American consciousness ― ones where the scares seen in our headlines influence the ones that invade our big screens.

As Susie says in “Suspiria” with cryptic menace, “Why is everyone so ready to think the worst is over?” But in Hollywood, the worst sometimes yields the best movies.

“Halloween” is now in theaters. “Suspiria” opens in limited release Oct. 26.

[ad_2]

Source link