February 2, 2025

Home About About the Editors Contact Us Press

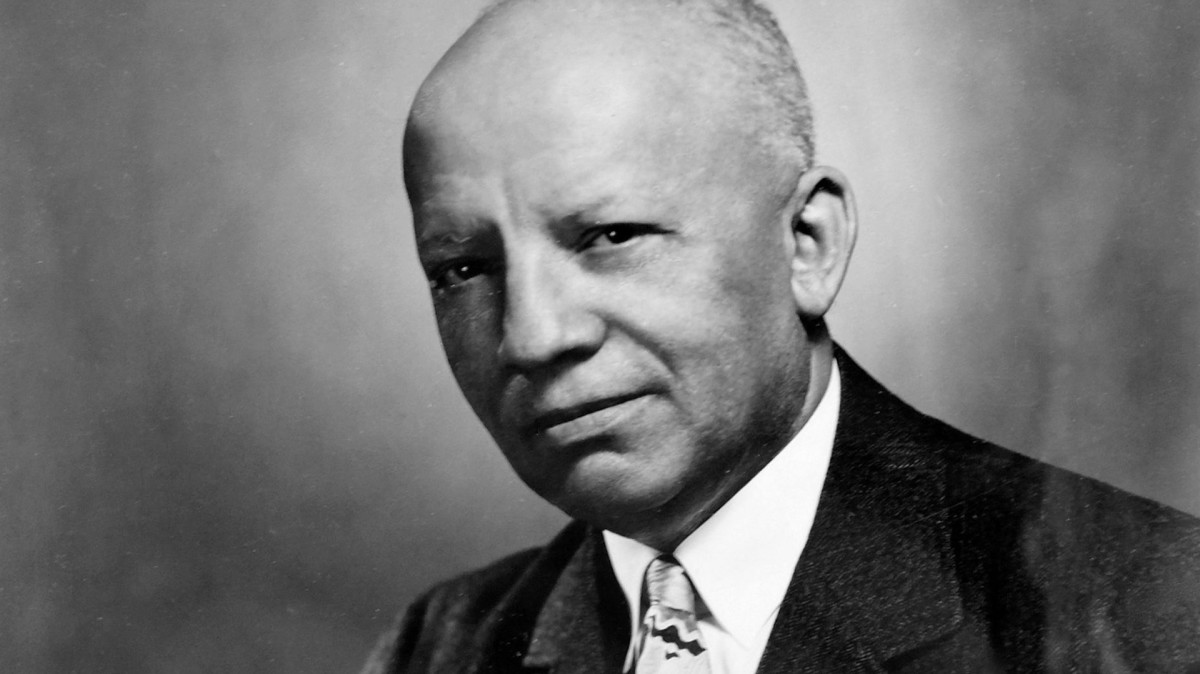

Born in 1875 in Virginia to formerly enslaved parents who were never taught to read and write, Carter G. Woodson often had to forgo school for farm or mining work to make ends meet, but was encouraged to learn independently and eventually earned advanced degrees from the University of Chicago and Harvard.

It was at these lauded institutions of higher education where Dr. Woodson began to realize these new educational opportunities for Negroes were potentially as damaging as they were helpful, if not more so, as much of the curriculum was biased and steeped in white supremacy.

In 1916, Dr. Woodson helped found the Journal of Negro History with Jesse E. Moreland, intent on providing scholarly records and analysis of all aspects of the African-American experience that were lacking in his collegiate studies.

As Dr. Woodson researched and chronicled civilizations in Africa and their historical advancements in mathematics, science, language and literature that were rarely discussed in academic circles, he also criticized the systematic ways Black people post-Civil War were being “educated” into subjugation and self-oppression:

“The same educational process which inspires and stimulates the oppressor with the thought that he is everything and has accomplished everything worthwhile, depresses and crushes at the same time the spark of genius in the Negro by making him feel that his race does not amount to much and never will measure up to the standards of other peoples. The Negro thus educated is a hopeless liability of the race.”

In 1926, Dr. Woodson began promoting the second week of February as Negro History Week. He chose this week in February intentionally, as it overlapped the birthdays of abolitionist activist Frederick Douglass (February 14) and President Abraham Lincoln (February 12) aka “The Great Emancipator.”

Supported and cross-promoted by several African American newspapers in the U.S., recognition and celebration of Negro (or African-American) History Week was slowly adopted through state departments of education (eg. Delaware, North Carolina, West Virginia) and in city schools (eg. Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York City).

Dr. Woodson spent decades advocating for excellence in the education of Black students and demanding school systems across the U.S. eliminate curricula designed deliberately to “mis-educate” Black children while promoting the fallacy of white superiority.

In 1933 he published a collection of his articles and speeches titled The Mis-Education of the Negro (available to read for free in the public domain), spreading his message and mission for unbiased and expansive education even further.

“When you control a man’s thinking you do not have to worry about his actions. You do not have to tell him not to stand here or go yonder. He will find his ‘proper place’ and will stay in it.”

By the time Dr. Woodson died in 1950, a significant amount of mayors across the U.S. supported and acknowledged Negro History Week.

By February 1969, more than a decade into the Civil Rights Movement and less than a year after the assassination of civil rights activist Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., students and educators at Kent State University proposed the first Black History Month — then celebrated it in February 1970.

Six years later, after meeting with civil rights leaders Vernon Jordan, Bayard Rustin, Dorothy Height and Jesse Jackson, as part of the nation’s bicentennial celebrations, it was President Gerald Ford (a Republican!) who officially acknowledged and co-signed the significance of Black History Month for all U.S. citizens:

“In celebrating Black History Month, we can take satisfaction from this recent progress in the realization of the ideal envisioned by our founding fathers. But, even more than this, we can seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of Black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history.”

So, even though this year the current administration has dusted up a pause on the celebration of Black History Month within federal agencies (don’t let the doublespeak of a Proclamation fool ya), Dr. Woodson’s good and lasting work of a lifetime will continue to be acknowledged, shared and celebrated this year, on its official centennial next year, and for all time — for the people, by the people.

Sources:

Published in African-American Firsts, Anniversaries, Commemorations, Education, History and U.S.

Your email address will not be published.