[ad_1]

Beverly Little Thunder remembers her community’s reaction when she first came out on the Standing Rock reservation in the 1980s.

“I was told that women like me were taken to the desert and shot,” she said. “It was devastating.”

In the early 1990s, Little Thunder helped create the term “two-spirit,” an umbrella term for LGBTQ+ Native Americans. She vowed she would not return home “until all of my two-spirit brothers and sisters were welcome.”

Years later, on a cold October night in 2016, Little Thunder sat in car headed south on Highway 1806 from Bismarck, North Dakota. As the car slowed down and pulled up to a security gate at the #NoDAPL resistance camp, the elder rolled down her window and asked a young volunteer where she could find the two-spirit camp. That weekend, Little Thunder and other two-spirit leaders were officially welcomed by the Oceti Sakowin leadership in a grand entry ceremony organized by Lakota activist Candi Brings Plenty.

It was the first time Little Thunder had been home in 32 years.

“Going to Standing Rock and having that welcoming,” she said, “it was so healing. I had never dreamt I would live to see that happen.”

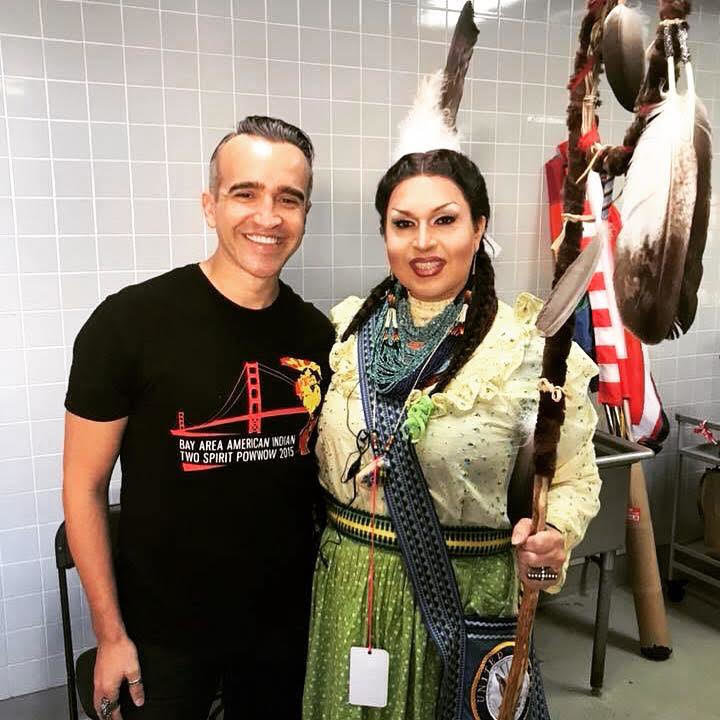

Courtesy Rebecca Nagle

Back in 1993, Little Thunder and other LGBTQ+ Native American advocates met in Chicago to discuss the creation of the first book by and for LGBTQ+ Native Americans. At the time, anthropologists were using the word “berdache” to describe Native people who did not adhere to Western gender and sexual norms, which translates to boy prostitute in Prussian. In an effort to institute their own term, the intertribal group shared teachings from their different cultures.

They arrived at two-spirit because “in many tribes if you are a two-spirit person, you embody both the masculine and the feminine,” Little Thunder explained.

Today, there are over 40 regional two-spirit societies and an international two-spirit council.

While sometimes outsiders confuse two-spirit as synonymous with trans, it is actually an overarching term for all LGBTQ+ Native Americans. Two-spirit is also pan-Indian, meaning it represents different cultures and tribes. In the U.S. there are over 570 federally recognized tribes, and each has its own teachings, words and roles for what people in Western Society call LGBTQ+.

In the Cherokee language, Wade Blevins is ᏄᏓᎴᎢ ᎤᏓᎾᏙᎩ or other-spirited. “A lot of traditional people are starting to go back to their own language,” said Blevins, a citizen of Cherokee Nation living in Jay, Oklahoma. “I think that’s the next step forward for us, to identify with who we are tribally rather than on a pan-Indian level.”

The Cherokee language has 10 different pronouns, all of which are gender neutral. A very specific worldview is encoded in a language that has four different words for the English “we” but no way to say “he”. After generations of boarding school (and even public school) teachers punished children for speaking their language, only 1 percent of Cherokee Nation citizens are fluent, and most are over the age of 60.

Indian boarding schools were just one of several policies the U.S. government enacted in the 20th century to assimilate the surviving Native American population. (Other policies included forced adoptions of Native children, the outlawing of Native religions, blood quantum to limit tribal enrollment, urban relocation programs and land allotment.) In the resulting trauma and cultural loss, knowledge about and respect for two-spirit people’s traditional roles were forever changed.

“[Two-spirit people] had a specific place in our tribe and in our community, which included child care, care for the dead and medicine,” Blevins said. “A lot of the younger Native people are not aware that we even existed.”

For Cherokees, the last person who carried the knowledge of two-spirit medicine died recently and unexpectedly. “Part of that information was passed on, but not all of it,” Blevins said.

Mico Thomas sees a similar culture of silence surrounding two-spirit people in their tribe, Chickasaw Nation.

“In our community, there are a lot of us, but it’s an unspoken thing,” Thomas said. “If you don’t talk about it everything is great, but you mention it once and then you are a pariah.”

Thomas’ great-grandfather was a preacher in the Chickasaw church. After he died, the family inherited his Indian bibles, hymn books and sermon notes. Thomas came across a sermon they think came from the 1950s condemning the leaders of a local ceremonial ground for allowing trans people to dance. Rather than being upset by the censure, Thomas’s first reaction was to feel validated, citing the fact that it’s difficult to find any historical information about two-spirit Chickasaws.

Courtesy of Mico Thomas

“I got really excited that this was going on back then at our stomp dance grounds, which meant to me that it’s very entrenched in our culture,” Thomas said. “There were more of me!”

Today, Thomas lives in San Francisco and helps organize the only public two-spirit powwow in the United States. The Bay Area American Indian Two-Spirit Powwow celebrated its seventh event last February with more than 6,000 people in attendance. At the powwow, all people are allowed to dance and compete in their chosen gender categories. It has become one of the largest Native gatherings in the region.

Overall, two-spirits are gaining visibility in Indian Country. This past March, the largest powwow in the United States, Gathering of Nations, honored two-spirit people during its grand entry. As another sign of progress during the weekend’s events, Trudie Jackson announced her candidacy for president of the Navajo Nation.

In urban settings, Jackson, who is pursuing her Ph.D. at the University of New Mexico in American studies, introduces herself as a transgender Diné woman, but she says within her own community she is introduced by her four clans. “I want people in my tribe to know that if you go get an education, you can come back and apply that knowledge as a leader,” said Jackson.

As part of her campaign platform, Jackson wants to renew a push for same-sex marriage in Navajo Nation that was voted down by the tribal council in 2005. Many two-spirit people like Jackson are working to change laws in their tribal nations, as the Supreme Court decision to legalize marriage equality in the U.S. does not apply to the sovereign governments of tribes.

As two-spirit people have gained recognition ― as progressive political candidates or #NoDAPL resistance leaders ― the term has entered mainstream, non-Native vernacular. “I hear so many people who will say, ‘I’m two-spirit. I’m both male and female,’ who are non-Native. Its offensive,” said Little Thunder. “It’s a privilege white people don’t realize that they’re using.”

Homophobia and transphobia were forced upon Native communities with a violence that white society has not experienced. For Little Thunder, the struggle to find language and acceptance as a two-spirit person who’s still grappling with the brutal legacy of colonization is fundamentally different than the struggle for people in the mainstream LGBTQ+ community.

The increased acceptance of two-spirit people, which Little Thunder has fought tirelessly for, is part of her community’s total recovery.

“Because of the Western thought that was imposed on our communities, we didn’t have the privilege of saying who we were,” says Little Thunder. “And it’s taken us a long time to finally find that voice.”

#TheFutureIsQueer is HuffPost’s monthlong celebration of queerness, not just as an identity but as action in the world. Find all of our Pride Month coverage here.

[ad_2]

Source link