We bring news that matters to your inbox, to help you stay informed and entertained.

Terms of Use and Privacy Policy Agreement

WELCOME TO THE FAMILY! Please check your email for confirmation from us.

OPINION: Richard Roundtree’s groundbreaking portrayal of John Shaft was a turning point for Black art, culture and self-identity, but it is also a superhero origin story.

Editor’s note: The following article is an op-ed, and the views expressed are the author’s own. Read more opinions on theGrio.

I stood up.

In 2018, while writing a profile on Samuel L. Jackson, I was sequestered in a makeshift office on the set of the “Shaft” reboot, where I had been summoned during the cast and crew’s lunch break. I had never been assigned to an entertainment beat, so I had no idea why I was singled out. I assumed that I had broken an unwritten rule of set protocol. Had I creeped out Regina Hall or asked director Tim Story too many questions? Was Samuel L. Jackson going to call me a “motherf*cker?”

As it turned out, someone on the set told Jackson about a paper I wrote for a film class during my undergrad years. Jackson thought the premise of the paper was fascinating so, during his lunch break, he strutted into the room carrying a styrofoam container and all of the self-assured confidence that he invokes. Regina Hall, who is as strikingly beautiful in person as she is in high-definition IMAX, stopped by the room and joined in. As if I were a student of Black nerddom taking notes from real-world scholars, I listened to stories about meeting James Earl Jones at an audition, the Marvel Cinematic universe and the history of Black film characters.

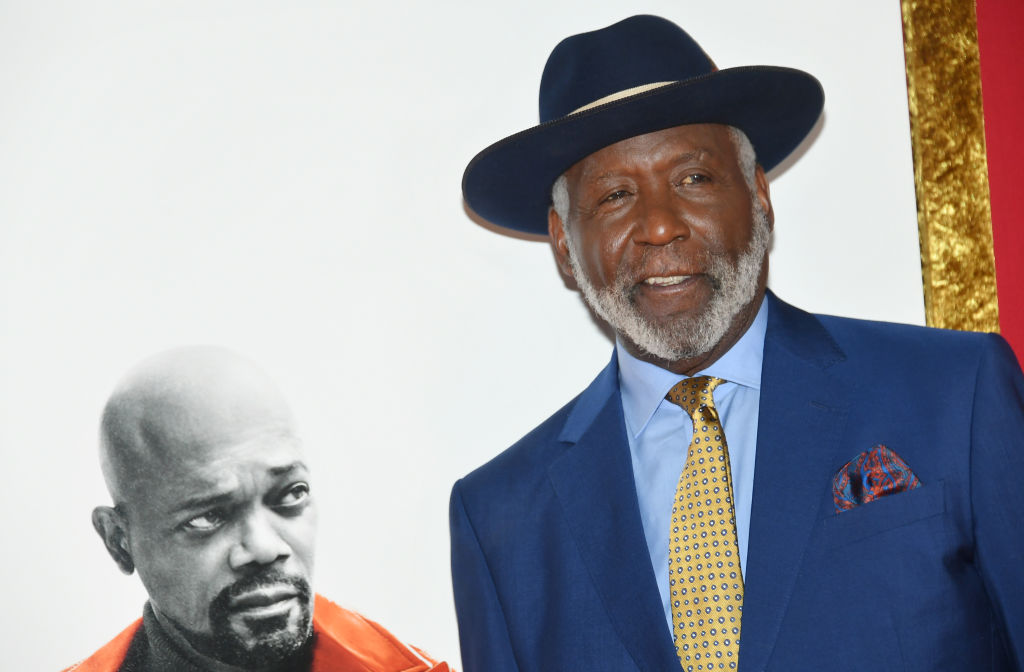

My back was to the door, but I could tell something Black had just happened. Hall stopped mid sentence. Jackson straightened his back, put his fork down and nodded in my direction. Unsure of exactly what I should do, I deferred to the familiar protocol of Black churches and stood up as if a choir was marching into the sanctuary. Adorned in a midnight blue, Clark Kent-style fedora was a Holy Ghost; a Black Superman.

Richard Roundtree was in the room.

“Ok, now ask him,” Jackson said before returning to his plate. Hall could tell I was flustered. Or maybe I was flabbergasted. Perhaps, I was feeling the holy spirit. Still standing, I tried to gather myself while Jackson summed up the premise of the article that prompted our conversation. I may have mumbled, “This is really happening!” when Mr. Roundtree leaned back in his chair. I’m sure I thought about pinching myself.

“That’s a good one, man” he said, laughing to himself… or God.

But before he could reply, Nick Fury, Mace Windu, Mr. Glass, Frozone and the only man to ever exterminate snakes on a plane simultaneously chimed in. “Don’t worry; we already decided on the answer,” said Jackson.

“Yes, Richard Roundtree was the first Black superhero.”

To be clear, John Shaft was not the first Black hero on film.

Actors like Paul Robeson, Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte regularly played Black characters with dignity and integrity. But because the film industry is an industry, filmmakers – both Black and white – often whittled away the defiant, rebellious parts of Black male protagonists. They were not submissive or overly passive, but they were agreeable enough to satisfy the palates of white audiences. While admirable, they were not super.

In a world where portrayals of Black life can be seen on movie screens and streamed on Tubi, it is impossible to explain Richard Roundtree’s outsized influence on Black culture. Roundtree’s on-screen persona is embedded in the braggadocious bars of your favorite rapper. His low-key confidence defined “swag” long before it was a word. While the Black Panther comic book may have preceded Roundtree’s film debut, most Black people had never seen the character created by a white man when John Shaft burst into the Black consciousness.

Six years before “Abar, the First Black Superman” earned the title of the “first Black superhero film,” nearly a half-century before Chadwick Boseman revealed to me that his Black Panther strut was “half Obama, half Roundtree,” Richard Roundtree landed the titular role in what director Gordon Parks called “the first picture to show a black man who leads a life free of racial torment.”

Made for a paltry $500,000, “Shaft” made $13 million dollars from audiences that were reportedly 90 percent Black. While “Cotton Comes to Harlem” may have ushered in the “Blaxploitation” movie era a few months earlier, Richard Roundtree’s portrayal of Shaft was different from the prototypical characters that defined the genre. He was a fully realized Black man whose world was “black and proud of it, but not obsessed with it,” wrote reviewer Maurice Peterson, who extolled the virtues of “a character whose life is firmly rooted in the reality of today’s black experience.” And, while many writers will use the words “masculine” and “throwback” to describe the Roundtree’s on-screen character he created, Shaft’s progressive attitude was ahead of its time.

“He moves through Whitey’s world with perfect ease and aplomb, but never loses his independence, or his awareness of where his life is really at,” writer Vincent Canby explained. “When a friend of his – a white homosexual bartenderbar tender – —gives him a rather hopeful caress, Shaft is not threatened, only amused. He has no identity problems, so he can afford to be cheerful under circumstances that would send a lesser hero into the kind of personality crisis that, in a movie usually ends in a gunfight, or, at the least, a barroom brawl.”

When asked about the groundbreaking role’s place in the Black film canon, Roundtree attributed the success of the character to director Gordon Parks. “It was my first feature film,” he explained. “I just did what Gordon told me to do.”Although he humbly acknowledged that Boseman cited John Shaft as an influence, when it came to heroes, Roundtree deferred to his predecessors, citing Robeson’s acting in “The Emperor Jones” and the title character of “The Great White Hope,” a role Roundtree previously played in theaters. While those characters were written by white men for white audiences, Roundtree agreed that John Shaft was different. “That’s why they called it Blaxploitation,” explained Roundtree. “To reduce its importance. When Dirty Harry came out the same year, Gordon said: ‘I wonder why they don’t call it whitesploitation?’”

Jackson agreed that Roundtree influenced his on-screen performances and believed it opened the doors for Black actors during an era when Black art and Black filmmaking were becoming more militant, more outspoken and less dependent on white Hollywood constructs. Noting that the character’s legacy spans multiple generations, Hall added that she was proud to be part of what she called the “Shaft cinematic universe.”

Jackson agreed that Roundtree influenced his on-screen performances and believed it opened the doors for Black actors during an era when Black art and Black filmmaking were becoming more militant, more outspoken and less dependent on white Hollywood constructs. Noting that the character’s legacy spans multiple generations, Hall added that she was proud to be part of what she called the “Shaft cinematic universe.”

By the end of the conversation, Roundtree tacitly accepted the jury’s verdict. Perhaps, for generations of Black filmgoers, John Shaft occupies a special place. He was an unapologetic, strong, defiant man who fought for his community. Still, Roundtree disagreed with one particular aspect of the entire premise.

“Maybe was a hero,” Roundtree said. “But what was his superpower?”

Everyone in the room knew the answer. But instead of chiming in, they waited for me to respond. I did not stumble, nor did my flabbers feel a speck of gast.

“His Blackness,” I replied.

Michael Harriot is an economist, cultural critic and championship-level Spades player. His New York Times bestseller “Black AF History: The Unwhitewashed Story of America” is available everywhere books are sold.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku, and Android TV. Please download theGrio mobile apps today!