[ad_1]

On a Sunday afternoon in February 1880, a young black Catholic left his family and friends behind in Quincy, Illinois, to travel to Rome ― all because American Catholic seminaries refused to accept a black man as a student.

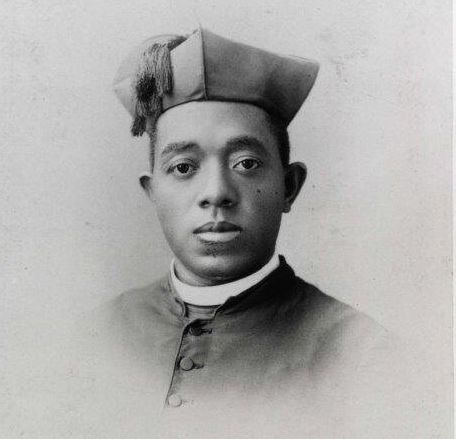

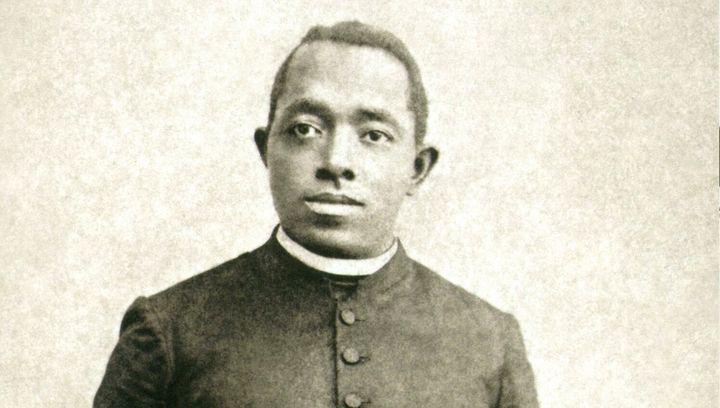

Decades later, that man ― the Rev. Augustus Tolton ― is one step closer to becoming a Roman Catholic saint.

Pope Francis declared on Tuesday that Tolton is “Venerable,” which means the church recognizes that he lived a life of “heroic virtue.” This is the second step in a generally four-part canonization process.

Although two other black American Catholics ― Henriette Delille and Pierre Toussaint ― have been declared Venerable, there are currently no black American saints.

The Most Rev. Joseph N. Perry, an auxiliary bishop of Chicago who has been championing Tolton’s sainthood cause, said Francis’ declaration on Wednesday illustrates Tolton’s holiness and perseverance “against great odds.”

“Fr. Tolton’s story represents the long and rich history of African American Catholics, who have lived through troubling chapters and setbacks in our American history,” Perry said in a statement.

Tolton was born into slavery in Missouri in 1854, the son of parents whose masters required their slaves to be baptized into Catholicism. His mother, Martha Jane, escaped with her children to Quincy, Illinois, in 1862. Martha Jane tried enrolling her precocious son at the parish school at their church, St. Boniface in Quincy. But other families at the predominantly white, German church revolted ― parents threatened to withdraw their membership, while Augustus was tormented by his classmates. After a month, he was forced to leave the school.

Racism continued to impact Tolton’s educational trajectory as a young man. When it became clear that he was called to become a priest, he had trouble finding a seminary in America that would agree to take him. He was eventually accepted into a seminary in Rome, where he was ordained. He’s believed to be the first Roman Catholic priest who publicly identified as black.

After his return to Quincy, Tolton confronted racism from some white Catholic priests who were upset that his Masses were attracting white parishioners. He was pressured into transferring from Quincy to Chicago, where he helped build the city’s black Catholic community and served its poor. It was exhausting work that took a toll on his health. Tolton died of heatstroke and uremia in 1897, at the age of 43.

Perry said he believes Tolton’s “work isn’t done.”

“Lessons from his early life as a slave and the prejudice he endured in becoming a priest still apply today with our current problems of racial and social injustices and inequities that divide neighborhoods, churches and communities by race, class and ethnicity,” Perry said. “We will continue to honor his life and legacy of goodness, inclusivity, empathy and resolve in how we treat one another.”

According to Catholic tradition, the church needs to attribute two miracles to Tolton’s intercession before he can be officially declared a saint.

There are numerous Catholic saints of African descent ― St. Augustine, St. Benedict the Moor and St. Martin de Porres, among others. At least 11 U.S. Catholics have been recognized as saints, but none is black.

Reynold Verret, president of Xavier University of Louisiana, America’s only historically black and Catholic college, told HuffPost that he is “overjoyed” that Tolton is one step closer to being a saint. His university is leading a national effort to advance the sainthood causes of several African American Catholics.

“The canonization of African Americans is a profound and a precious affirmation of God’s love for all mankind and significantly would affirm God’s Black creation,” Verret said.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this article said Pope Francis declared the Rev. Augustus Tolton “Venerable” on Wednesday. The Archdiocese of Chicago sent its press release on Wednesday but said the pope took the action on Tuesday. Language has also been amended in light of the fact that others of African-American descent, such as the Healy brothers, also entered the priesthood but publicly identified as white.

This article has been updated with comment from Reynold Verret.

REAL LIFE. REAL NEWS. REAL VOICES.

Help us tell more of the stories that matter from voices that too often remain unheard.

[ad_2]

Source link