[ad_1]

To be an Orson Welles completist is a lonely business. When the filmmaker died in 1985, he left behind a trail of unfinished projects, and yet when his swan song, The Other Side of the Wind, was finally released last year, it was not an inescapable cultural event but mere content for Netflix’s insatiable maw, digested and soon forgotten. With Mark Cousins’s exhumation of his artwork in a new documentary, The Eyes of Orson Welles, we may be scraping the bottom of the barrel.

The filmmaker’s drawings are not entirely unknown; in 1955, the BBC broadcast Orson Welles’ Sketchbook, a series of intimate 15-minute shorts he illustrated in pen and ink. But they are having a moment. Orson Welles Portfolio, published by Titan Books last month, reproduces drawings from the Welles estate, some of which are expected to hit the market imminently. The impetus of Cousins’s film, however, is a box of drawings that the filmmaker “found” in a New York storage unit. In it are youthful portraits drawn in Ireland and Morocco, as well as sketches for an unmade Heart of Darkness and a Julius Caesar to have been shot in Mussolini’s EUR. He supplements these works with those in Welles’s archives at the University of Michigan and in the Arizona home of Beatrice Welles, Orson’s youngest daughter, who likely gave him the key to that storage unit.

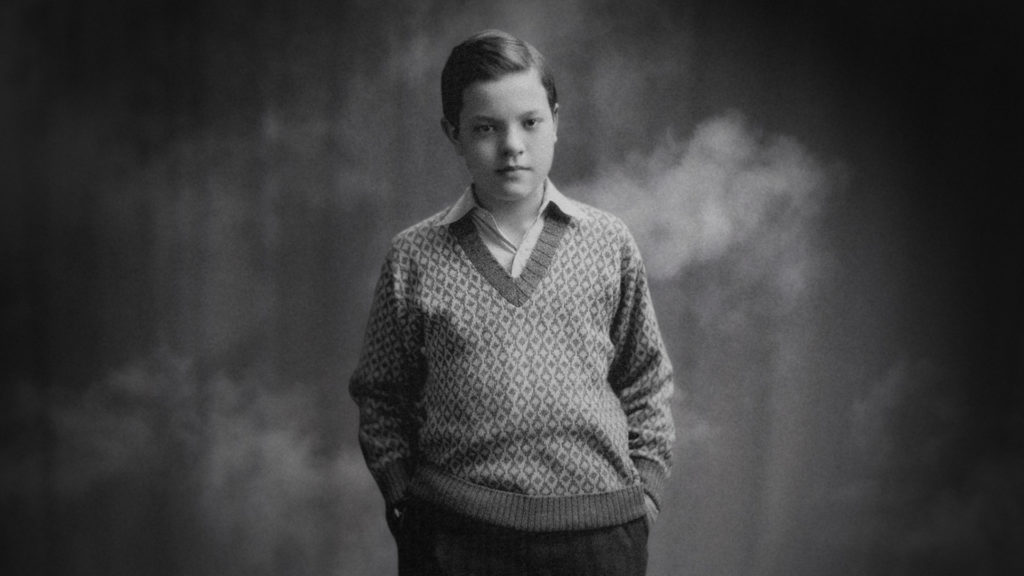

Cousins, who’s best known for his 15-part television series The Story of Film, is primarily interested in examining Welles’s artwork for insights into his aesthetic development and psychological preoccupations. According to Cousins, the filmmaker’s original ambition was to become an artist, although this is doubtful, since he was already directing at 11. Furthering his curious thesis, he makes much of Welles’s mere weeks at the Art Institute of Chicago, and claims he went to Ireland at 16 to draw. But if that was the purpose, why did he spend most of that sojourn onstage at Dublin’s Gate Theatre?

The narration, written as a multipart letter to Welles, is structured along a biographical track, with departures for sections on his relationships, recurring themes, and obsessions. Cousins is particularly interested in Welles’s passion for social justice, showing a clip from Sketchbook in which Welles recounts his role in hunting down the police officer who beat an African-American soldier, Isaac Woodard, blind in South Carolina in 1946. Observes Cousins, “The fact that Woodard ended up blind seemed to dig into you, a visual person.”

Cousins is a solid reader of visual art, filmic and otherwise. “You took a line for a walk,” he says, paraphrasing Paul Klee as he connects one drawing to a rollercoaster in The Lady from Shanghai (1948). He compares the nets and grills Welles often shot through to the hatching and shading in his charcoal drawings. And his art-historical references are equally on point. A scene in Mr. Arkadin (1955), in which who is shooting and who is getting shot matters less than the play of angles and shapes, shows the influence of Cubism. He compares the Constructivist-style sets in The Lady from Shanghai to a work by Alexandra Exter and its famous hall of mirrors scene to Eadweard Muybridge’s motion studies. The actors in Chimes at Midnight (1965) roll in bed as if they had been staged by Tintoretto. Soldiers peering through the oculus over Othello and Desdemona’s bridal chamber recall Andrea Mantegna’s trompe l’oeil ceiling at the Palazzo Ducale in Mantua.

However, to enjoy these insights one must contend—as one did in The Story of Film—with Cousins’s narration, in a singsong that tends to upspeak. Here the repeated appending of “didn’t you?” is particularly grating. After interrogating Welles for 95 minutes, Orson (voiced by Jack Klaff) is finally allowed to talk back, in a lugubrious rumble that in no way resembles the jocular article.

Also, as in The Story of Film, there is the not-small matter of what we’re looking at when we’re not looking at old movies. The film begins with Cousins musing about how Welles would miss the World Trade Center in the Lower Manhattan skyline. But since the buildings opened 12 years before his death and he had not lived in New York for decades, I doubt he had much attachment to the Twin Towers. Over contemptuous shots of Times Square, Cousins drones on about the “guy who thinks he’s Charles Foster Kane” in the White House. As his Osmo Pro glides slowly up the TKTS steps we hear an excerpt from a Mercury Theatre broadcast of Archibald MacLeish’s ominous play The Fall of the City, implying that we are fiddling while America burns.

Returning to significant locations in Welles’s life, he offers as the theater where Welles met future Mercury Theatre co-founder John Houseman not the Booth but what is now the Hirschfeld, on the next block—presumably because Kinky Boots is playing there, providing another opportunity to excoriate our tacky culture. (And when Houseman met Welles, he was more than a “grain merchant-turned-theater producer”—he had already directed Gertrude Stein and Virgil Thomson’s Four Saints in Three Acts.)

Most egregious is footage shot on West 125th Street at Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard—a block from a bustling Whole Foods—that is supposed to illustrate a “New Depression” he claims the U.S. economy is suffering. (A depression with a 10-year bull market and 3 percent unemployment? Perhaps Producer Michael Moore can explain.) He begins the shot with two bags of garbage on the curb—clear recycling bags filled with cardboard—and then pans to a woman waiting for a bus. A bus! The horror!

“Save the pieces,” as they used to say in the New York Times late-show listings. Lacking a completed Merchant of Venice or The Dreamers or Don Quixote, we Welles fanatics will take what we can get.

[ad_2]

Source link