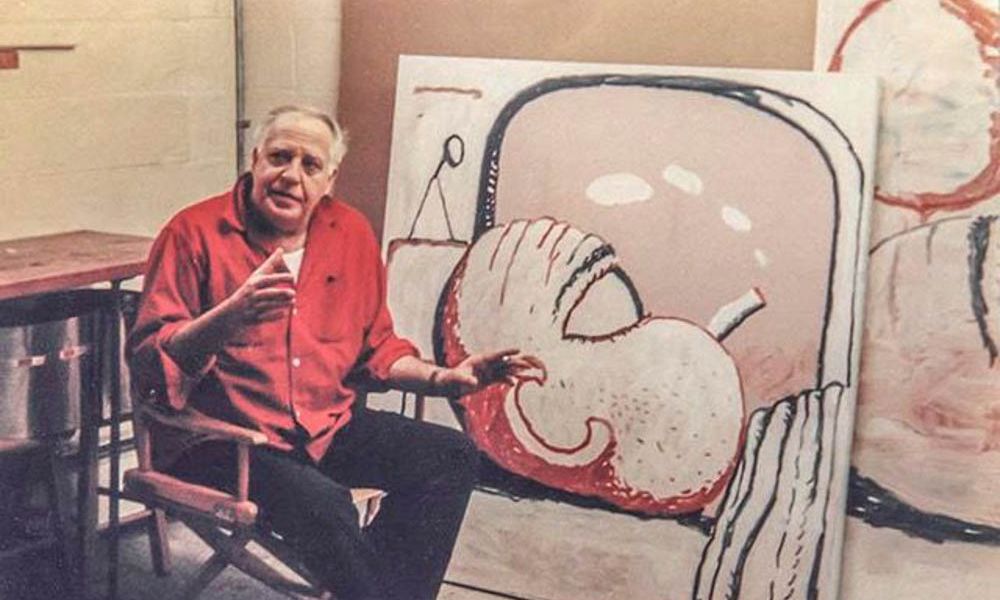

Philip Guston with Smoking I (1973); from the late 1960s until his death in 1980, the artist’s focus moved to figuration, away from the abstraction that characterised the earlier part of his career Photo: Barbara Sproul

The stellar and rigorous catalogue accompanying the exhibition Philip Guston Now addresses head on the Ku Klux Klan imagery that forced the show’s controversial postponement. These two smaller books, timed for the first stop in Boston, are quietly no less vital in grasping Guston’s contribution to post-war American art and his abiding significance to contemporary painters.

I Paint What I Want to See is a collection of Guston’s interviews, writings and lectures, with a cluster of notes made in his studio, over 20 years. Because Guston had what turned out to be a late-career rupture from 1968 to his death in 1980, disavowing abstraction for figuration, his before-and-after thinking is inevitably fascinating. As early as 1960, in an interview with David Sylvester, he wishes he had “the courage to paint my face” and reflects on his “constant doubt about this whole thing”. By 1972, he tells a Yale Summer School audience what happened when he finally went “through the mirror” and began wrestling with figurative imagery: “about two-and-a-half or three years of just ecstasy. Just pure joy.”

You sense that giddiness, even when he talks in the same lecture about the most troubling aspect of that shift: the Klansmen paintings. Elsewhere Guston was clear that, among much else, the hoods were a despairing response to US politics and a recognition of his own complicity. But once he decided to pursue this imagery, he says, “I was off. You couldn’t catch me for two years.”

The anxiety-ecstasy vacillations punctuated Guston’s life. What he sought through painting are dualities: solidity and ambiguity, the known and the mysterious, traits he identifies in his artistic heroes Rembrandt and Piero della Francesca, the latter here discussed at length. Guston is drawn to Piero’s “cosmic” quality, his profound mystery, discussing the idea of the enigma in painting in a coruscating conversation with the poet Clark Coolidge. Regarding one of a series of paintings he made representing a single book, Guston delights in the fact that it is “just there and yet it’s shaking…throbbing, or burning or moving”: a remarkably apt description for late Guston’s unique power.

Among those who best captured the painter’s final-decade achievements was Ross Feld, another poet and a rare moral support after he’d been shunned by the art world—even by old friends like the composer Morton Feldman—following his figurative rupture. Before Feld died in 2001, he had begun to gather his thoughts on Guston in a book, eventually published in 2003, along with the pair’s correspondence and now reissued.

Their friendship began after Feld had written on Guston’s 1975 show at the David McKee Gallery, New York, and continued up to Guston’s death (over dessert at a neighbour’s home in Woodstock, New York, we learn). Feld’s book is part memoir, part critical response to the late work, and thus occupies a distinctive place in the Guston literature. The correspondence reflects how great a tonic Feld was to the embattled and eventually ailing painter: “I’ll say it!—You are Valéry—Proust, and I must be Cézanne,” Guston writes in his last letter to Feld, no doubt with tongue in cheek. He then exclaims: “I’ll shout it right out—you inspire me to paint again!”

Alongside Rob Storr’s vast tome, A Life Spent Painting, and Philip Guston Now, these books confirm how successfully Guston achieved the enigmatic quality he sought, however perceptively his work is interpreted. Guston perhaps put it best: the work of marvellous artists, he wrote, “is strange, and will never become familiar”.

• Philip Guston, I Paint What I Want to See, Penguin Classics, 288pp, £9.99 (pb), published 28 April

• Ross Feld, Guston in Time: Remembering Philip Guston, NYRB Classics, 192pp, $17.95/£14.99 (pb), published 24 May

• Ben Luke is review editor and podcast host at The Art Newspaper and art critic for the Evening Standard