[ad_1]

“Don’t look away from me! Look at me and tell me it doesn’t matter what happened to me.”

You can’t see Maria Gallagher’s face in most of the now-viral video footage from her elevator confrontation with Sen. Jeff Flake, but once you’ve heard it, it’s near impossible to forget her voice. She’s yelling at an elevated decibel through tears ― forceful, clear, direct and deeply pained.

Gallagher, along with Ana Maria Archila, both survivors of sexual assault, cornered the Arizona Republican on Friday as he tried to enter an elevator on his way to a meeting on Capitol Hill. As the senator cowered, looking pained, avoiding eye contact, Archila and Gallagher went off at him for nearly five glorious, heart-wrenching minutes. They weren’t merely sad that Flake had announced he would be voting to advance Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination out of committee and to the Senate floor. They were, as Archila explained on CNN the following day, “enraged.”

This is a refrain I have heard often over the past two years from my women colleagues, friends, family members, random acquaintances on Twitter and interviewees over the past two years. At this point, to say that American women are angry is to state the obvious. Of course, they ― we ― are. Across the nation, women are angry, and also outraged, and also full of rage, and also burning, and also wanting to burn it all down. This anger can be messy, directed at a plethora of targets in sometimes contradicting ways. But this anger also has the potential to be incredibly potent, especially when it isn’t isolated.

We have seen women’s anger at work before: During the early 20th century fight for the vote, during the 1960s and ’70s when women marched for abortion rights and equal pay and racial justice and the right to hold credit cards under their own name, in the early ’90s after Anita Hill’s moving testimony against Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas was met with derision from the white male senators who questioned her. In 2018, we are in the midst of a critical and potentially revolutionary moment; a political moment in which American women are, as journalist and author Rebecca Traister put it, “coalescing in anger again” in ways that are necessarily “messy” and “frenzied,” because “were it any other way, nothing would ever change.”

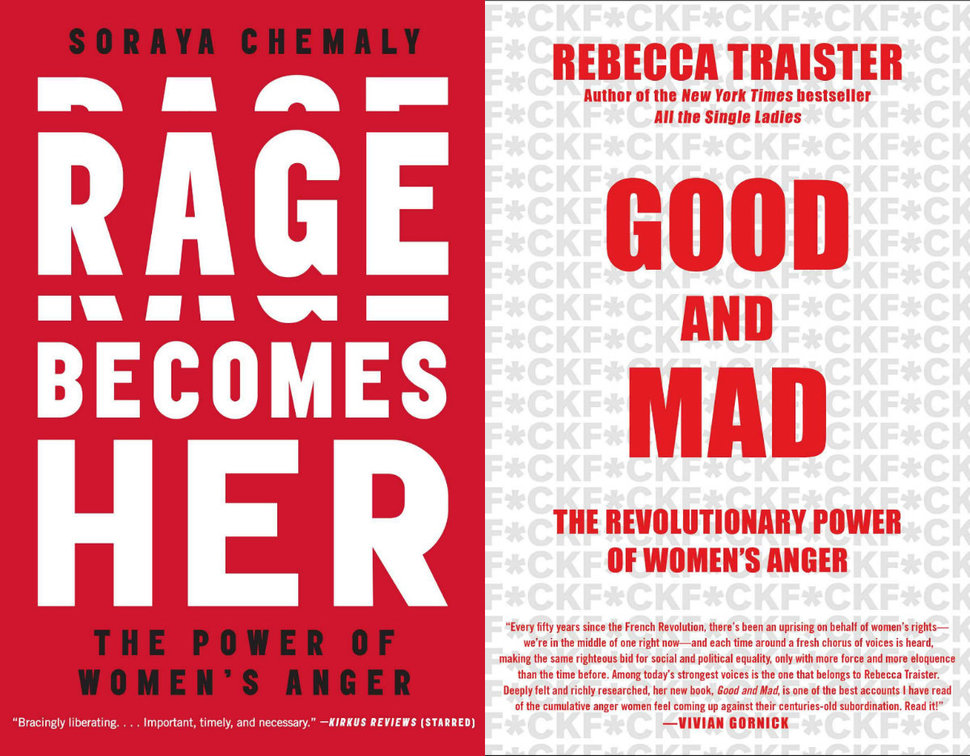

It is this current rage-filled moment and its potential that is at the center of two new and essential books: Traister’s Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger and feminist writer and activist Soraya Chemaly’s Rage Becomes Her: The Power of Women’s Anger. Chemaly’s and Traister’s books cover similar ground but in different ways. They are perfect companion pieces, working in tandem: Chemaly showing us exactly why women are (and have every right to be) so massively, unyieldingly angry, and Traister drawing a blueprint for how that unyielding anger can be channeled collectively, as well as where this current collective burst of female rage fits into a long legacy of angry American women throttling toward political change.

It would be impossible to fit all of the reasons that women are enraged into this essay or even into a book. Women’s anger could fill volumes upon volumes, but Chemaly does an excellent job of giving the uninitiated a rundown of female rage.

Women are angry because the realities of pregnancy are shrouded in sanitized terms and reproductive justice feels forever fleeting. Women are angry because they are perpetually pushed into the role of caretaker at home, with little institutional support, and then scorned for expressing discontent in that role. Women are angry because they spend their lives navigating public spaces full of harassment and private spaces full of abuse in a society with, as Chemaly writes, a “deep cultural resistance to taking women’s fears of male violence seriously.” Women are angry because they spend their youth being overtly sexualized and their later years being rendered invisible. Women are angry because if their skin color is not white, they face increased threats of violence, even from the authority figures that are tasked with keeping communities safe. Women are angry because they are told to bottle up their anger and then that bottled up anger ends up linked to physical pain, both chronic and acute.

Women are angry because, according to Chemaly, despite the fact that they report “feeling anger more frequently, more intensely, and for longer periods of time than men do,” they also are more likely to associate that anger with powerlessness rather than power. Women are angry because even when they express all of this pain, it is often not taken seriously.

But more important than its existence is understanding that this anger, this female rage, contains untapped potential. “In anger, whether you like it or not, there is truth,” wrote Chemaly.

Since the 2016 presidential election ― buoyed by the groundwork laid by activists involved with movements like Occupy Wall Street and, most significantly, Black Lives Matter ― that truth has become more visible, spilling out of women’s bodies and into the streets and onto ballots. As Traister put it, we are seeing the “reemergence of women’s rage as a mass impulse.”

The key word there is mass. Where Good and Mad shines is in its explicit (and successful) attempt to go beyond an exploration of individual anger and zero in on the effect of collective anger and its political outcomes.

Simon & Schuster

We are already seeing the beginning results of this mass impulse. Women are marching in unprecedented numbers. They are seeking elected office, and some of them are winning. They are founding youth-led political movements. They are turning the pain of their Me Too stories into a sustainable rallying cry. After all, anger has always been a key component of social change, from abolitionism to the women’s suffrage movement to the fight for abortion access and marriage equality. But the path our collective anger paves always looks neater in hindsight, and the political gains are always peppered with losses. Losses that, like Hillary Clinton’s loss to Donald Trump, can set off a whole new wave of anger with the potential to be expressed productively.

To understand the way these moments of anger, which add up to movements, have ebbed and flowed in the past might allow us to sustain this current one. It might allow us to make our anger really, truly count.

“Our job is to stay angry, perhaps for a very long time,” Traister wrote, specifically directing this advice to the newly woke and the privileged among us. “That it will take a long time shouldn’t scare us,” she wrote a few pages later. “It should fortify us.”

As both Traister and Chemaly drive home, however, there is always a cost to being angry. From Flo Kennedy to Serena Williams, angry women have made history, but they’ve also often paid a steep price. Angry women have been taught by the culture that their anger is unhealthy and corrosive and ugly, practically the worst thing a woman can be. Their rage has been erased from history books, like with Rosa Parks, a veteran activist who is remembered in the public imagination as a docile middle-aged seamstress. Or their roles in social change have been downplayed altogether, like with LGBTQ activist Sylvia Rivera, who helped launch the seminal Stonewall Riots. They’ve been denied access to professional advancement. They’ve been shunned. They’ve been arrested. They’ve been physically harmed.

The truth is that the anger women feel is not distributed evenly among us, and nor are the consequences for expressing that anger. Women are divided along race, class, generational, political and geographical lines, so some of the anger that women feel is (understandably!) directed at each other. That’s what makes a political coalition of the majority so difficult to maintain, and also so very formidable and terrifying to those who benefit from the status quo. As both Good And Mad and Rage Becomes Her makes clear, this female rage is not new and the challenges that come alongside it are not new either. We have been here before, and we will likely be here again. The real test is whether our collective anger can sustain.

There is a meme making the rounds on social media platforms among women I know and women I don’t know this week. In it, Ilana Wexler, Ilana Glazer’s character on “Broad City,” looks aghast at someone out of frame. “How ‘am’ I?” she asks, using finger quotes around “am.”

It works as a mood summarizer specifically because of its exasperated quality. “How are you?” isn’t even a question many women can fathom answering at this point, because the baseline is so far from fine. “How am I?” we want to say. “Pretty fucking terrible and pretty fucking pissed off, and we’ve been pissed off for millennia and there are no words to express the rage that burns inside of us on a daily basis, threatening to consume our whole bodies and come out of our eyeballs.”

To be angry at injustice is to be human. At its best, our rage can sustain us and get us through the worst of days and weeks and months and years. It can transform our own lives, and, perhaps most important, the lives of those who have been holding on to far more righteous rage than we can even imagine. What Chemaly and Traister are telling us, in no uncertain terms, is to stand with our angry sisters, rage-filled shoulder to rage-filled shoulder, staring out into a future we hope can be better.

[ad_2]

Source link