[ad_1]

The Great Recession was, somewhat famously, a “mancession.” Men faced higher unemployment rates because they were more likely to work in industries, like construction and manufacturing, that were harder hit during the crisis over a decade ago.

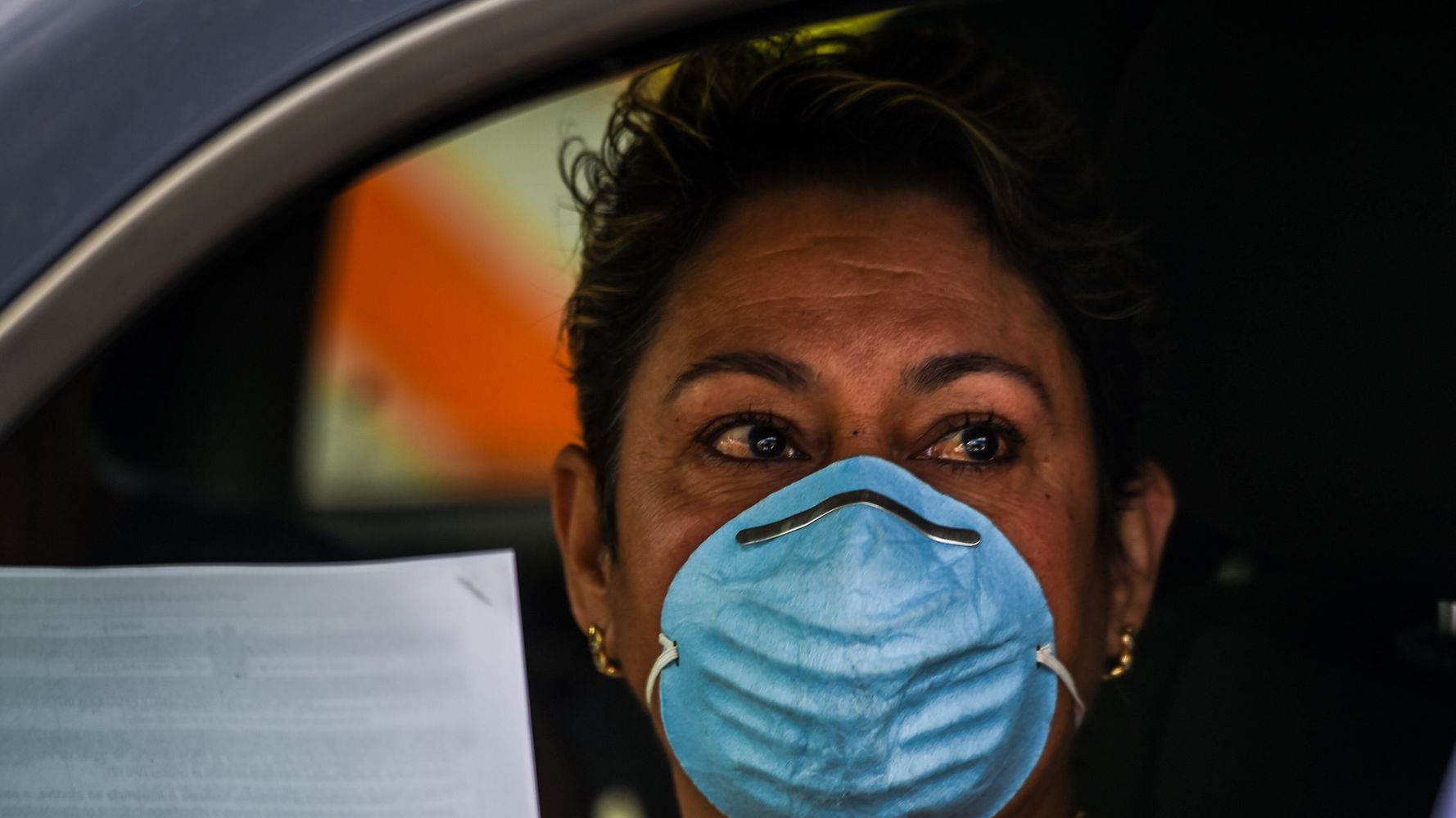

Not this time. Call it the She-cession or Femcession, if you must, or just take note: In the COVID-19 downturn, women, particularly women of color, are losing jobs at a higher rate.

The demographics of the losses are hard to track using federal data, which still hasn’t parsed the details of the millions of lost jobs of the past few weeks. But a new investigation from the Fuller Project sheds some light on the damage. According to the nonprofit news organization, women make up a clear majority of the workers who applied for unemployment insurance during the last two weeks of March in at least five states.

“This is like nothing we’ve ever seen before,” said Sarah Ryley, who conducted the investigation along with Fuller Project CEO Xanthe Scharff. “It’s not like a normal crisis.”

Typically during this time of year, women make up 25% to 40% of people receiving unemployment, Ryley said. Now they make up more than one-half to two-thirds, the nonprofit’s reporting found. For the past four decades, men have always borne the brunt of job losses in a recession. Not this time.

Why Women?

The slowdown in 2008 was a “production recession,” explained C. Nicole Mason, president and CEO of the Institute for Women’s Policy Research. People stopped making and building things as loans got harder to obtain. Crudely speaking, a lot of workers who made stuff ― typically men ― lost their jobs.

This time, the slowdown began in the service sector. With everyone stuck at home, Americans are not paying for other people to do things for them. Hairdressers, restaurant workers, hotel housekeepers and retail clerks have all been thrown out of work. And women hold the majority of these jobs.

Another difference between the mancession and now: The manufacturing and construction jobs lost back then were fairly well-paying. Some were even unionized. That meant those men may have had some financial cushion ― either savings or benefits ― to fall back on.

The women losing their jobs now were underpaid. Remember the gender pay gap? Women comprise two-thirds of the lowest-paid workers in the U.S. These service jobs have terrible benefits: less paid sick leave, no health insurance, etc.

“That just really creates a very precarious situation,” Mason said.

One particularly vulnerable group right now is domestic workers ― the nannies, housekeepers and other care providers who work in other people’s homes. About 90% of these workers are women, and they already labor for low wages, mostly without benefits.

Their situation is dire during the pandemic: 72% were out of work this week, according to a new survey from the National Domestic Workers Alliance. And 70% said they weren’t sure if clients would hire them again after the pandemic.

Across the country, women are less likely to be able to telecommute. Only 22% of women, compared to 28% of men, are able to work from home, according to a working paper issued this month by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Not only are women getting hit harder by the service sector shutdown; they’re also facing enormous pressure at home. School and day care closures mean that some women with jobs can no longer go to work, particularly those who are single mothers, because they have children at home.

Costco Is Not An Option For Everybody

Theoretically, some of these women could find work at the few places that are currently hiring ― grocery store chains, Amazon, etc. But that’s exponentially harder with kids at home.

Jobless women are just scraping to get by. Lauren Slaughter, a 32-year-old divorced mother of two in Akron, Ohio, paid only half her $1,500 rent on April 1, after getting laid off from her job as a business development manager at the end of March.

“I just wanted to make sure I can buy groceries and keep the lights on in the house,” she told HuffPost.

Slaughter’s layoff came the same day that her 3-year-old’s day care center shut down. Her 7-year-old had been temporarily going there, too, after the public school shut its doors.

The logistics of job hunting during an economic freeze, while also caring for two young kids at home, are daunting. And Slaughter’s unemployment check still hasn’t arrived. “It’s been a struggle trying to do everything all the time myself. It’s very isolating being home with just your kids,” she said.

Martha Rodriguez lost her part-time job at a preschool in Washington state, where she lives with her newly underemployed husband and their two kids.

She considered taking on some seasonal work at Costco. But her husband, who lost one job, is still getting some hours on another job, and they couldn’t figure out a way to manage the schedule now that she’s home-schooling their 8- and 11-year-olds.

“I need to pay someone to take care of my kids so I can go find another job,” Rodriguez said. But that’s not worth it if the job wouldn’t cover the cost of child care ― assuming she could even find a job. Now she and her family are just getting by using food banks and waiting for her husband’s jobless benefits.

The Numbers Are Still Coming In

The economic crisis happened incredibly quickly. Just last week, 6.6 million people filed for unemployment. And data on who exactly is losing work takes time to come out.

The latest official unemployment rate of 4.4%, for example, doesn’t yet include the more than 16 million workers who’ve applied for jobless benefits in just the past three weeks. Some estimates put the actual unemployment rate at 13%.

The last national look we have at the share of women who are unemployed comes from the second week of March, as the coronavirus job losses started up.

Even then, women made up the majority of the newly unemployed, according to an analysis of the data from the Institute for Women’s Policy Research. Of the 701,000 jobs that vanished that week, 412,188 were held by women.

“Women’s job losses outnumbered men’s in almost all sectors of the economy,” the report said.

Of course, those numbers now look tiny compared with the millions more out of work.

The Fuller Project’s investigation went directly to state unemployment agencies to get more recent data.

Ryley asked nearly 40 state unemployment agencies to provide numbers on the gender makeup of those workers who filed for unemployment benefits in the last two weeks of March, when COVID-19 layoffs and shutdowns swept the country and 8.7 million people were thrown out of work.

Five states replied and the numbers were striking. In three states ― Minnesota, New Jersey and Virginia ― women represented nearly two-thirds of those filing for jobless benefits.

In New York, women made up more than half of the 450,000 people who filed for benefits. In the previous quarter-century, the share of women filing for claims in that state had never topped 40%. In Oregon, women typically comprise a third of filers. During the last two weeks of March, they were the majority.

Black Women Are Hardest Hit

The Fuller Project numbers don’t note racial differences because the states were not able to parse the data that way, Ryley said. But a survey released Thursday from the women’s advocacy group Lean In shows that Black women, in particular, are feeling these job losses.

Fifty-four percent of Black women said they were laid off or furloughed or had their hours and/or pay reduced because of the pandemic ― compared with 31% of white women and 44% of Black men. Only 27% of white men said this.

Black women also were the most likely to worry about paying for basic necessities. Sixty percent were worried about making rent or paying the mortgage, compared with 24% of white men. And 43% of Black women were worried about paying for food.

Zaborah Roane of Raleigh, North Carolina, had only 10 cents in her bank account until Friday when she got her last paycheck ― for about a week’s work. The 48-year-old told HuffPost that she was furloughed from her job as a day care worker at the end of March. Her pay, just $15 an hour despite her two decades of experience, had been reduced in the weeks leading up to the day care center’s closure. She used the money to buy some soap and cleaning supplies. Her 30-year-old daughter is helping out with groceries.

“It’s a stressful situation,” she said. “I have my 5-year-old grandson here because his school is closed. He keeps me grounded. If I stood back and really thought about it, it gets me down. I’m trying not to be down. I pray a lot.”

Roane, who is a member of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, doesn’t know how she’ll pay rent next month. Her roommate covered her in April. She’s applied for food stamps and unemployment insurance. She’s waiting.

“The financial fallout of this is really breathtaking,” Rachel Thomas, the president of Lean In, told HuffPost. “It is heartbreaking to start to internalize the economic impact on everybody, but particularly women.”

To be sure, men are facing their own horrifying gender gap during the pandemic. The coronavirus appears to be more likely to be fatal in men than women.

Policy Is Falling Short

Ryley and her co-author Scharff argue that all states should have to provide statistics on who’s filing for unemployment benefits. Without knowing who is losing their jobs in this crisis, it’s hard to craft a good policy response.

So far, Congress has failed to come up with a rescue package that deals with the unique reality of COVID-19 unemployment. The paid leave policy passed as part of a stimulus bill last month leaves out 75% of workers ― many of them women.

“I’m always trying to look for, is there a bright spot or a potential silver lining?” said Thomas. “Right now, I have to be honest: I don’t feel optimistic.”

A HuffPost Guide To Coronavirus

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link