[ad_1]

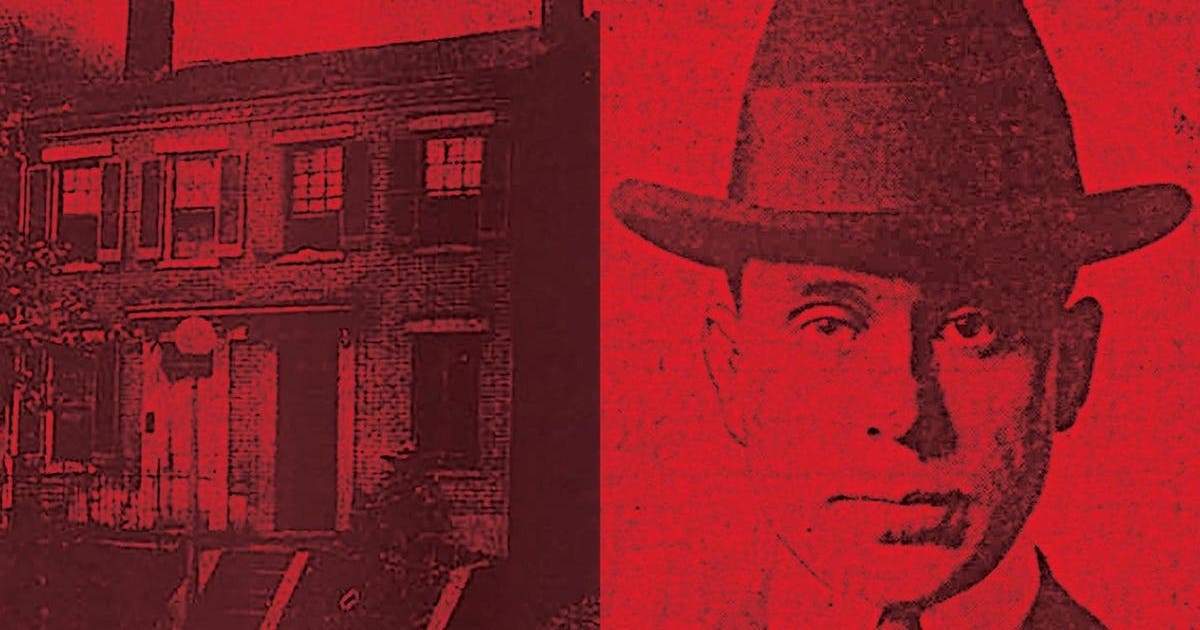

Ben and Carrie Johnson peered out the second-story window of their brick rowhouse at 220 G St. NW. On the sidewalk below, dozens of white men clustered around the glowing street lamp, pointing up at them. Trapped and surrounded, the Johnsons feared for their lives.

It was the night of Monday, July 21, 1919, and the city of Washington was engulfed in racial combat. In expectation of trouble, Ben, a 52-year-old African American man, had obtained a .38-caliber revolver. With his 17-year-old daughter Carrie, he watched the chaotic scene outside, where black residents, taking refuge on the roofs of their houses, were hurling rocks at the gathering whites.

An African American musician returning from a late-night gig heard someone shout, “Get the n—–!” A flying brick struck a police officer in the head, dropping him to his knees. Gunshots sounded from the houses across the street. A car full of white men came roaring up the alley next to the Johnsons’ rowhouse. More gunfire rang out. Two Metropolitan Police patrolmen approached, and bystanders told them the shots had come from the second floor. The patrolmen sent for reinforcements. Within minutes, two Army trucks disgorged two dozen armed Marines who surrounded the rowhouse, ready for orders.

James Weldon Johnson — poet, activist and field secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People — called it the Red Summer, a season of blood in America: From April to November 1919, the United States experienced a rolling series of race wars that might be described as a neo-Confederate offensive. Fifty-four years after Appomattox, riots broke out in at least 26 cities. Lynchings spread; by year’s end, 76 black men would be lynched, the most in a decade. Everywhere, the story was the same: White mobs, often encouraged by newspaper attention, mobilized to attack their African American neighbors for crimes real and imagined.

[ad_2]

Source link