[ad_1]

Protestors filled the streets of San Juan, Puerto Rico, for 12 days prior to Ricardo “Ricky” Rosselló announcing his resignation as governor on July 24.

MARINA REYES FRANCO FOR ARTNEWS

Marina Reyes Franco is an independent curator and writer based in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

I was in a bar in Old San Juan when the news broke on July 24 that Ricardo “Ricky” Rosselló had resigned from his post as the governor of Puerto Rico after 12 days of unprecedented nationwide protests that shook the world, as the “oldest colony” finally revolted against the incompetent and corrupt government he embodied. His fate was sealed after the leak of 889 pages of a Telegram chat chock full of derogatory language, violence, and disregard for people’s lives. I was not expecting it to come so abruptly. As the streets erupted in celebration, we rejoiced in our newfound collective power.

Artists and art professionals of all kinds took part in this movement, joining the hundreds of thousands of people from all walks of life who protested on horseback, on motorcycles, in kayaks, and even underwater using scuba gear, as others intermittently shouted “¡Ricky renuncia!” on the beach. These cacerolazos took place every night at 8 p.m., as did morning yoga sessions, queer balls, and thousands of memes that captured everybody’s imagination. In what was probably the most Puerto Rican protest ever, there was even a night of “perreo combativo,” a trap and reggaeton street dance party, where the steps of the San Juan Cathedral became an altar to the country we want to have.

At night, the protests were not without violence, as the police dispersed the crowd at 11 p.m., with the announcement: “your actions are not protected by the Constitution,” which ultimately provoked clashes with protesters that resulted in arrests, injuries, and one car being set ablaze by a police projectile. This time the pressure was on from all sectors of society, not just the “same people,” for the governor to step down. The demonstrations built on years of on activism by LGBTQIA+ and feminist groups, coupled with rage at the government, particularly because of their disastrous response to Hurricane Maria.

The call was amplified by celebrities, who shared their demands via social media and came out to protest too. However, most of the events emerged from random online communities and people who posted flyers calling for decentralized protests, like the one that invited people to join in a national strike on July 22 that spread like wildfire. Countless people provided creative input in organizing calls for protest, producing hundreds of flyers, T-shirts, posters, and videos, and even coding. Satire, humor, anger, mourning, and righteous indignation have been echoed publicly, mixed with expressions of joy. These events feel eminently cathartic.

I’ve been most impressed by the way people have reacted toward official representations of power. #RickyTeBoté (@rickytebote on IG and Facebook) is a movement encouraging the removal and disposal of the governor’s official photo from government offices. The first group to do so featured three older women, including attorney Lourdes Muriente, whose deceased ex-husband, pro-independence leader Carlos Gallisá, was mocked in the now infamous chat. The much-criticized bronze sculptures of U.S. presidents around El Capitolio were covered up in various ways, including with the same kind of orange traffic cones that were revealed to cost $500 each in another separate government scandal. The Christopher Columbus monument in Plaza Colón at the entrance of Old San Juan was also graffitied with text that called out his role in the colonization of the Americas.

These demands are anti-colonial and emancipatory, and I believe there is a critical mass now ready to hold accountable politicians and their private sector cronies for their past actions. While we wait for the results of various ethics and criminal investigations associated with the administration, protests continue. Before Rosselló resigned, he appointed Pedro Pierluisi to succeed him, in what ultimately proved to be an unconstitutional assumption of power, according to the Puerto Rican Supreme Court. Now Wanda Vázquez, the former Secretary of Justice, has been named governor—our third in less than a week. The struggle for power continues among the political class, but people are organizing popular assemblies and pushing back on what is widely perceived as a game of musical chairs among the ruling political party.

Much is being said about how things seem different now, a feeling that there’s a generation of Puerto Ricans who have grown up without the so-called benefits of the Island’s colonized status as a U.S. territory. Instead, we’ve inherited an unsustainable debt and crushing austerity measures imposed by a Fiscal Control Board. We are looking forward to the future and creating the government that Puerto Rico deserves. In the meantime, we are taking pride in being ingobernable.

Below is a selection of contributions from artists and cultural workers from Puerto Rico and its diaspora about their experiences—and outlooks on the future—following the protests.

A protestor holds up a sign reading, “A million voices of the people demand the resignation of Ricky Rosselló today.”

MARINA REYES FRANCO FOR ARTNEWS

José López Serra, photographer and director of Hidrante, an art space in Santurce

Yo no sé tu

Yo vine a perriar

???????

Un perreo tan hasta’bajo

que termine sinking Colón’s monument

???????

A freak dance tan hasta’bajo

que socave the corrupt machine del gobierno

???????

Un twerk tan hasta’bajo

that breaks los amarres del colonialism

???????

During [Governor] Pedro Rosselló’s administration in the 1990s, underground music, which would later be known as reggaeton, was persecuted and criminalized. There were elitist accusations and dismissals of the new creative expression. It seems fitting that his son should be toppled while people twerked.

Carina del Valle Schorske, writer

Thursday [July 18], the morning after photos of the Fortaleza protests revealed a vast river of 500,000 people flooding the narrow streets of the old city, I flew to the Island from New York to be counted among them. From a U.S. perspective, diaspora has long been a kind of dumping ground for Puerto Ricans forced to flee the failures of the colonial state. But diasporic Puerto Ricans don’t disappear, or stay put, or forget. In the few days I marched with my friends and family in San Juan, other Nuyoricans kept showing up, having canceled plans and called in sick with revolution to take our place in history. Somos más—not only are we more than the corrupt oligarchy that collaborates in our oppression, we are more than the bodies seen in the street. We move with the dead (always) and with the people dispersed by austerity politics. There are always more of us than the official account is prepared to admit.

Sofía Gallisá Muriente, artist and co-director of Beta Local, an arts organization in Old San Juan

It is impressive how the process has been turned into memes and audiovisual content with such extraordinary speed. There are artists creating posters and songs and whatnot, but artists also provide work strategies that contribute in many ways to these processes that don’t necessarily entail creating work for or inspired by the political processes. For me and definitely for Beta Local, the spaces of political action are enacted in everyday life, via invisible work and work processes, which we aim to strengthen by helping people meet and collaborate. It’s important to use the example of Puerto Rico to problematize the idea of “socially engaged art” (or worse, “artivism”), and examine how these events are covered in the media, which tend to emphasize the leadership of a couple of famous artists, or the artists who make work about the protests. Sometimes those approaches are very literal and simplistic. In Puerto Rico, perhaps precisely because there is no system that allows artists to completely professionalize their practices, they understand themselves as citizens, and art is something they do that permeates many other parts of their lives.

María José, poet and performer

I’m amazed at the creativity of the people. Every night at 8 p.m. is the cacerolazo. Opening your window and listening to your community expressing their indignation and anger at the status quo by banging their pots and pans is impressive. It also works to relieve stress! And it sounds like the war cry of an army of coquí frogs! A lot of us are proud to be Puerto Rican because we are experiencing our collective power at history-making levels. I feel very proud, but I am also worried that people’s main goal is to kick a misogynist out of office, and not to kick out misogyny from our society. I am worried that transphobia is seen as a marginal issue, instead of one of the most violent roots of our system. I am worried that many Puerto Rican men aren’t prepared to demand from themselves the same transparency we are demanding from our elected officials. This fight must be, above all, about truth and accountability. It is devastating to see violence inflicted against LGBTQIA+ communities without consequence. That is precisely what we must fight against. As a queer, trans, non-binary, femme artist, my main limitation is toxic masculinity and LGBTQIA+ phobia in Puerto Rico, and my main goal is to kick it out.

Maritza Stanchich, University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras

Whether it was Ricky Martin with speakers ablaze on a flatbed truck waving the rainbow flag, or everyday musicians playing bomba and plena percussion roadside during the historic march that drew nearly a million on July 22—with many marchers playing instruments of their own (scratching güiros or pounding tambourines)—an effervescence of arts buoyed the protests that ousted Puerto Rico’s governor, a key demand toward more systemic change in this Caribbean country and U.S. territory of 3.1 million, with more than 5 million living abroad often joining in via social media. Sustaining a dozen days of protest were the street theater collective Papel Machete, poetry at the microphone at daily rallies near the governor’s mansion, and the contagious creativity of the crowd: its chorus of witty chants, signs ranging from the comical to the sobering, body painting, graffiti with a message, and a carnivalesque performativity with the Puerto Rican flag. Yet behind such exuberance, public arts institutions struggle against annihilating austerity by a federal fiscal control board extracting $72 billion in debt from a two-party governmental system crippled by corruption, and locked into structural colonial constraints for managing the debt. Foundations and donors have supported select arts groups since the devastating hurricanes of 2017, but art schools, such as the Escuela de Artes Plásticas, Conservatorio de Música, and art programs at the University of Puerto Rico, are barely surviving. This broader malaise needs to be routed out. A far bigger task awaits, and Puerto Rico needs its artists more than ever to envision and enact such change.

Carola Cintrón Moscoso, artist and co-director of Diagonal, an arts space in Santurce

In a country where culture, art, and education have been under siege for years due to limited institutional support and budget cuts that restrict university programs, making art is an act of daily resistance. As a Caribbean woman and artist interested in the use of digital media, I have approached cultural and social practices in Puerto Rico as a collective right. I decided to participate by projecting my video game Infinite run: Defend the Island v.1 from the balcony of art space Souvenir 154 on a wall in Fortaleza Street on July 20. I’ve been listening to the breaths, the shouts, the silences, and the pauses that are also necessary to produce another rhythm, another space, another message, and another country. It is a priority, more so now than ever, to support the ties and networks of collaboration that have been created between artists and independent art spaces led by artists, as a form of resistance and transformation.

Fofé Abreu, lead singer of Fofé y los Fetiches, Circo, and Clarias

The artists are like blood valves where life runs from the unbreakable force of emotions, naked feelings, passions, and therefore the visceral force that moves us to fight for any cause that merits it. People see in the artists the representation of their intimacies and without having to say it, they develop a personal and mystical connection with the admired works or those proposals that they feel they represent because they are touched by some intellectual and/or sensitive fiber. The Puerto Rican people are extremely creative, and during this process of revolutionary awakening, artistic expression has been moving and impressive. This has definitely been one of the political events of greatest impact for the evolution of our country with a view to our existence in the 21st century, and there is no doubt that art throughout the range of its manifestations was there supporting us with its camaraderie and immeasurable complicity.

nibia pastrana santiago, lazy dancer and choreographer

On Monday, July 15, and Wednesday, July 17, 2019, I was peacefully manifesting alongside hundreds of Puerto Ricans at La Fortaleza, demanding Puerto Rico’s governor Ricardo Rosselló resignation; not only because of #telegramgate #rickyleaks, but also because of his government’s rampant corruption before, during, and after Hurricane Maria, his lack of action to declare an emergency state to address violence against women, the closing of public schools, and the budget cuts for health and the University of Puerto Rico. In summary—systematized corruption to destroy and sell Puerto Rico. Let me quote Edwin Miranda (one of the participants in the chat): “I saw the future… is wooooonderful…there are no puertorricans” [sic] (page 868).

ON BOTH OF THOSE EVENINGS I WAS AFFECTED BY TEARGAS. As a 2019 Whitney Biennial artist, i assume the uncomfortable position to make work in this political climate. I have been asked if i will ‘remove’ my work from the Biennial. I must say I love this question, as it poses an almost philosophical question about body and time-based work, like the one I do, which is: choreography. I already performed and did my work in the Biennial […] That is, my work is not something that can be uninstalled, the work in itself is my body in action; and my body since last week is marching, dancing, screaming, sweating, and protesting. I want the audit of the Puerto Rican debt, JUSTICE, no more police brutality and no more gas.

Derick Joel, musician, cultural anthropologist, and graphic designer

I did not study graphic design. My studies were in cultural anthropology, and I started doing graphic design when I made posters for the shows of my bands, and then it became a profession. I also entered the world of design out of economic necessity. Puerto Rican culture has suffered too much in recent years at the hands of the government in power. In addition to taking to the streets, I felt an obligation to create posters for the free use of protesters without making a profit. I wanted to give some tools so that people could convey the message. The truth is that I never imagined seeing a demonstration like this in Puerto Rico, and I am very proud of my people and of being Puerto Rican.

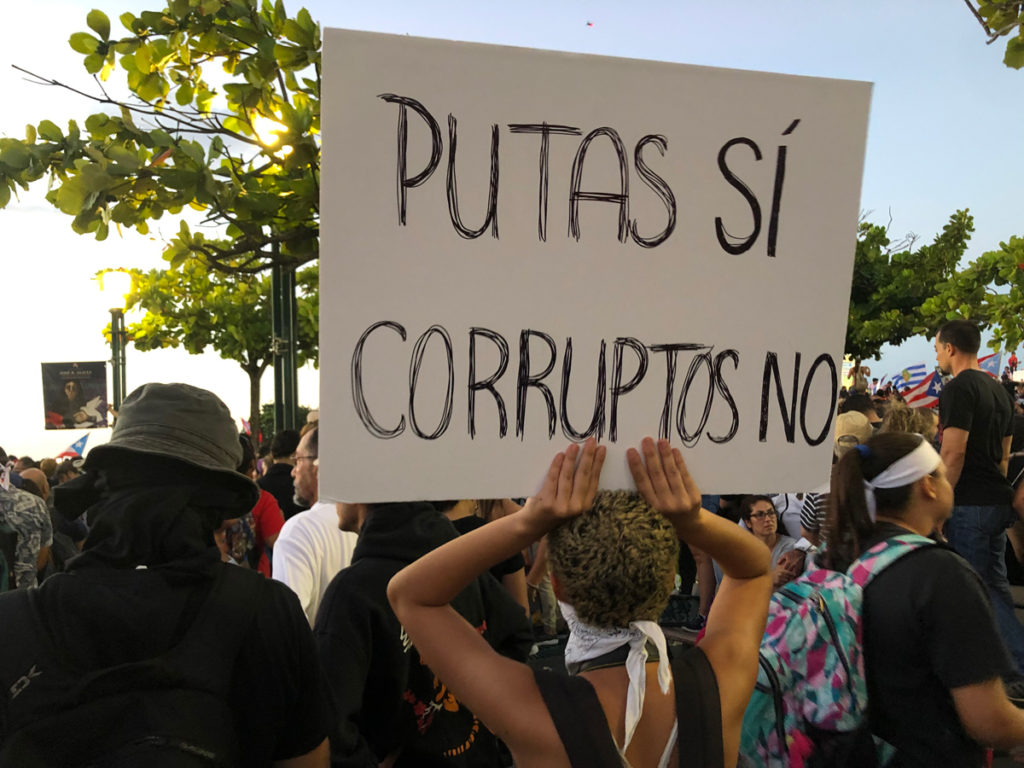

A protestor holds up a sign reading, “Whores yes, corrupt ones no.”

MARINA REYES FRANCO FOR ARTNEWS

Arnaldo Rodríguez Bagué, interdisciplinary artist and curator

When an entire archipelago protests against colonial, patriarchal, misogynistic, and homophobic violence we realize that the coming of the Caribbean islands does not stem from the unreachable monolith horizon but emerges from the deepest oceanic abysses, emerges below the horizon surrounding the island.

The artist Nibia Pastrana writes: “The revolution will be intra-island, watery, salty or it won’t be.”

The protests not only happened in the streets—the colonial cobblestones of the Island—but they have also taken place underwater and in the San Juan Bay; articulating a submerged political positioning of the insular-colonial body.

A protesting diver writes: “Not even the fish want him.”

It seems important for me to argue in favor of the decolonial forces of climate change. Those forces beyond the human that not only erode the sandy coasts and submerge the coastlines but also mobilize an archipelagic policy that counteracts the evaporation of island-colonial bodies. The forces of climate change will erode the colonial ruins of the Caribbean coast and feed the coast with the lost, stolen, and murdered in the half-millennium “sovereign” to come.

A meme by artist Ramón Miranda Beltrán says: “There is no revolution without beaches.”

As journalist and writer Ana Teresa Toro wrote, “There are hurricanes that devastate a country and there are countries that swallow hurricanes . . . and return them.”

Mikey Cordero, co-creator, Defend Puerto Rico

In any country or nation, you must always look to the writings on the wall. In Puerto Rico, the artist has always been the honest reflection of what is happening in the country. In 2016 an iconic door in Old San Juan was repainted to present the black-and-white Puerto Rican flag as a symbol of resistance. The art community in Puerto Rico has always rallied against injustice and colonialism. Now that same work is being acknowledged and used to lead the protest and rallies. People are uniting behind the art, and in today’s landscape of social media, the visual is the most powerful tool. As an artist, designer, photographer, and documentarian, I have always incorporated and collaborated with the work of the people on the front lines. The visuals we have created under the Defend Puerto Rico project for the current #RickyRenuncia campaign utilizes the voices of on-the-ground organizations and serves as a visual vehicle for the decolonization narrative and demands that THEY want the world to hear especially during times like this where dissent is co-opted by the politicians and ruling class.

Rubén Ramos Colón, poet

I think that La Fortaleza, as a building and symbol of the executive power, is a vestige of the colonial era that we must finally end. Whoever governs, if we continue to choose to have a unique, all-powerful figure instead of a representative parliament, must reside in their home and pay the expenses from their own salary. La Fortaleza must become a museum about the political history of our country, its gates and the street in front of it always open for the people. Politicians have to govern and live among us. They should endure traffic like the rest of us, or fix it for everyone. They shouldn’t hide from our daily realities. La Fortaleza must never again be a fortress in which to dig in, but a place for collective memory and its struggles. The country we are making together has to be forged in equity.

Christopher Rivera, owner and co-director, Embajada, a gallery in the Hato Rey

A few days ago, I spoke with artist Daniel Lind-Ramos about the events of the past two weeks in Puerto Rico, its Caribbean context, and the parallels between the protest march and the carnival march. The marches were organized in a very organic way and music plays a very important role in moving the nation. It’s very hard for me to just think from the arts community perspective in relation to rallying against the corrupt governor of P.R. and his administration. I want to believe that this has been a creative revolution, from the people, for the people.

I participated in the second and third nights of demonstrations in La Fortaleza, the latter was the first clash with the police. I was affected three times by tear gas and witnessed the brutality of the police. I saw a guy getting beat up with a baton, his head covered in blood. Later, I attended the July 24 protest at Union Square, where the diaspora let New York and the world know that Puerto Rico exists beyond its coordinates. We met in Columbus Circle, walked toward Times Square, occupying Seventh Avenue until we reached Grand Central Station. Since I live in New York, I try to inform as many people I can to let them know about what has been going on in P.R. I believe this was a huge victory from the people of Puerto Rico, but this is just the beginning of a fight against all the corrupt people and agendas against all Puerto Ricans. After Rosselló resigned, I thought of a famous Ramon Emeterio Betances quote from when we were invaded by the Americans in 1898: ¿Qué hacen los puertorriqueños que no se rebelan?! [What are the Puerto Ricans doing that they don’t rebel?!] He would have been very proud of this moment.

Tony Rodríguez

Those who aim to minimize or demonize the calls by Rey Charlie and the car rally crowd don’t know what they’re saying. They represent the caseríos [public housing], the streets, the barrios, the goddamn “Special Communities” as Sila [María Calderón, P.R. governor from 2001–05] called them. I know because I come from one, El Cinco, in Rexville, Bayamón, and we’re indignant and asking for our demands to be heard. I heard a leader of car rallies on TV saying they’ve put aside their differences and beefs between the different clubs “so that the governor respects us and resigns once and for all.” If that doesn’t mean anything to someone who thinks people just want to show up to party and make noise, they would be very wrong. They are organized and in full understanding of what’s happening. Nobody can mess with us now. These are the real streets, and they are on fire.

Eduardo Benson Silva, artist and activist

What is going in Puerto Rico is nothing short of astonishing. An organically organized, mostly leaderless movement of people swarmed government institutions and the islet of Old San Juan, to emphatically oust governor Ricardo Rosselló in less than 2 weeks. The generation that rose up to the occasion did so after growing up in the constant echo chamber of colonial rule, where the words corruption, crisis, and scarcity have shaped their bellies as well as their views of a future for themselves, their families, and their communities. This new generation can sense that, and are incensed by the cruel and psychotic nature of the Island’s ruling class that is evidenced in the leaked chat documents. I decided to read the chat out loud in public with several friends and strangers, because I found it hilarious and abhorrent that the president of the Senate, Thomas Rivera Schatz, said that he had not read it yet. We rented a tumbacoco (a pickup truck with a huge sound system) with crowdfunded monies, and proceeded to go through 300 pages in 6 hours in front El Capitolio, the local legislature. I plan on taking the event on the road.

Mine was only a drop in the bucket compared to the complete explosion of creative force that has come forth like a broken dam. People have picked up everyday objects and turned them into weapons of protest, not just lifting the cobblestones representing our colonial heritage to launch at riot police, but used orange transportation barrels as shields, as armor, brooms as placeholders for protest messages and art. The memes, so many memes. People adorned their bodies with war paint in the shape of the Puerto Rican flag, their faces as canvases, their bodies as exhibition rooms. In less than two weeks protest songs were composed in plena, rap, rock, and bomba. The flash mobs of kayaks, motor bikes, cyclists, and horses show a people whose need to express their discontent goes beyond the classic defeatist mentality that had plagued the Left on the Island for years.

None of this could have happened without the mostly underappreciated efforts of small groups of extremely hard-working folks, who have not allowed the island’s constant crisis mentality to paralyze them, and have been doing ant-like work for years, mostly in obscurity, like the work of Papel Machete; the activist organizing by Jornada Contra la Junta and AgitArte; the murals by La Puerta collective; as well as the now folk hero, Rey Charlie, who in a single week broke down so many barriers of misconceptions, bigotry, and poor shaming toward people from poor backgrounds, and all just by moving masses of motorcyclist caravans through the entire San Juan islet. The struggle is also the most intersectional movement in Puerto Rican history, with groups like la Colectiva Feminista and la Brigada Cuir, pushing forth new forms of radical leadership by women, and LGBTQIA+ organizers reaffirming themselves on the streets that for years have neglected them. We can only imagine what other things people will be able to creatively conjure after having found what power they have when joining forces, feet on the street. That they themselves are the beach lying beneath the pavement.

Raquel Torres Arzola, artist and educator

The events of the past few weeks were not convened or protested from ideological platforms by partisan leaders or prefabricated union structures. The traditional and boring circular picket line, accompanied by repetitive and aged slogans, was transgressed. What took place was the physical conglomeration of thousands of bodies celebrating as much as exercising protest and transgression, shaped only by urban architecture and the police line. These thousands of bodies were armed with firm, clear, and direct choruses whose political forcefulness did not need a language drawn from the annals of history, but the consensus marked by the temporal and political context: “Ricky, resign!” “We are more, and we are not afraid.” This weaponized language was accompanied by an equally irreverent flow and generational attitude that for decades has generated cultural manifestations such as hip-hop, reggaeton, and trap. In turn, these cultural manifestations have been used as a strategy to attack limiting, imposed, and demagogic canons on the body and on sexuality. Now, these notions are turned on their head by language as a weapon and from the body as the place of action, to occupy a territory as political scenario and generate a transcendental change in our history.

Teatro Breve is a comedy troupe that organizes stand-up events and creates plays and short videos. During the past few weeks, they’ve been organizing filming around calls for protests. The below three entries are from members of that company.

Lucienne Hernández, actor

We are the same as the whole country: observing, participating, digesting, and waiting. Israel [Lugo, the director] is doing the same thing that I remember him doing since the Telefónica [Puerto Rico Telephone Company] strike in 1998 from which I have a memory of him on stilts. Only now he had to interrupt the shooting of his first film.

Adiela Marie Arroyo, producer

The welfare of the crew is a priority so that a local project with the resources we have runs in the best possible way. For the demonstration on Wednesday, July 17, we advanced the morning call so that the crew could go to the march in the afternoon. For the Monday, July 22, national strike, we decided to take the day off because the cast and crew were so attentive to what is happening on the Island and eager to participate. These decisions involve additional costs and have an impact on the global shooting schedule. While we can accommodate space to support and share this historic moment, we will do it.

Naíma Rodríguez, executive producer of the Teatro Breve movie and director of Pública, an independent cultural center in Santurce

This movement has transformed us in different dimensions, but above all in our self-esteem and in what we are willing to accept. In the midst of the demonstrations, the cultural sector had to make adjustments and question what issues are the most important. We had to make changes to the agenda in Pública, like changing the dates of a programmed play and instead use the space to talk, to clear our head and conspire. As for the Teatro Breve crew, this historic event caught us right in the middle of production of our first film. The costs of filming are high and the political situation discourages investors, but we are joining efforts with people who have supported us since our beginnings, to put our principles and emotional well-being above all. We also activated the Teatro Breve characters of Guanina and Davidcito, to express two points: this fight was activated by women and it is a fight that exceeded protester stereotypes.

[ad_2]

Source link