[ad_1]

Fifty years ago this September, Arthur Ashe won the first U.S. Open. This was 1968—the year violent civil rights protests rocked cities across America; the year Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated; the year segregationist George Wallace won 46 Electoral College votes for president. And a man who had grown up prohibited from playing on his local courts because he was black won America’s highest honor in a sport that is still overwhelmingly white—and where even today Serena Williams, perhaps the world’s most dominant black athlete, was just made to conform to traditional (read: white) notions of how a woman tennis player should dress.

Ashe went on to win Wimbledon and the Australian Open, in a career that placed him 20th on Tennis magazine’s list of the greatest male players of the Open Era, released this year. He remains the only black man aside from Yannick Noah—whom Ashe “discovered” at a clinic in Cameroon—to win a Grand Slam.

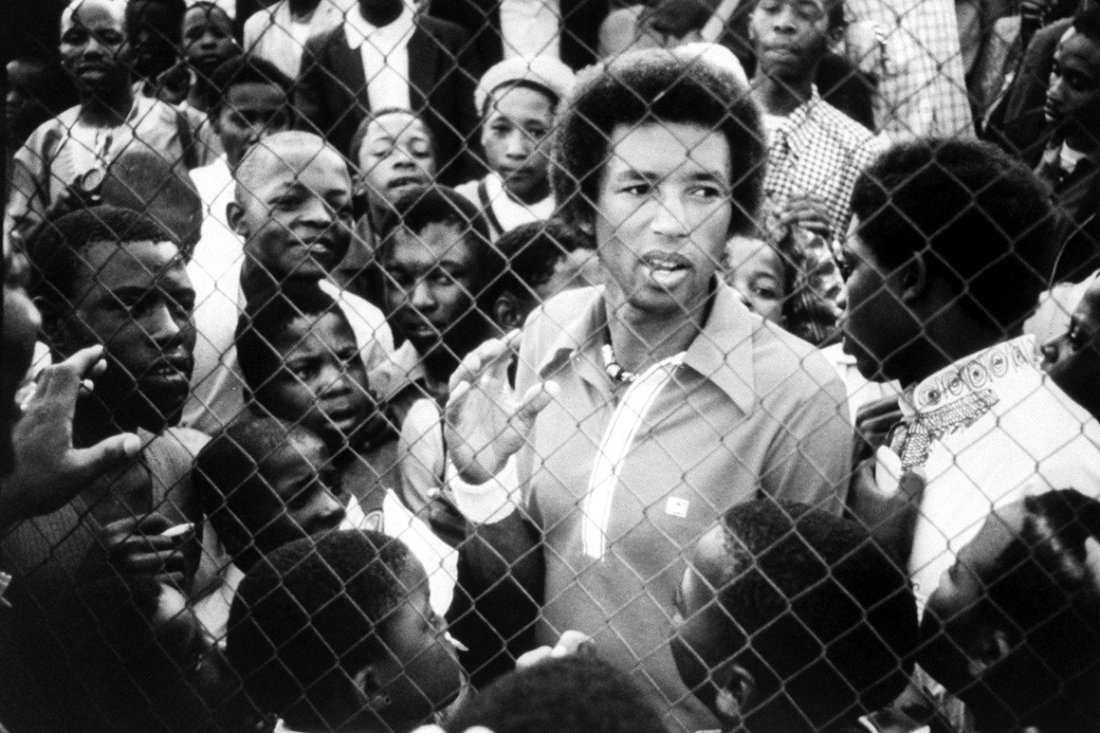

Beyond his groundbreaking tennis, Ashe, who died in 1993, is celebrated as a vocal champion for black rights for having marched against South African apartheid and the mistreatment of Haitian refugees, among other causes. Sports Illustrated named him “Sportsman of the Year” in 1992—13 years after he had played his last set of professional tennis. Earlier this month, in the New York Times, writer William C. Rhoden compared Ashe to Jackie Robinson for having “embraced the role of pioneer and resolved to use his new platform to join the fight that had been swirling around him.”

But the truth is more complicated: Ashe did not want to be a hero. To become one, he had to go against everything that made him successful in the first place.

[ad_2]

Source link