The ARTnews Accord: Stella McCartney & Sheila Hicks Talk About Mindfulness in Fashion and Art

Stella McCartney began her career as a fashion designer in the 1990s, most notably as the creative director of Chloe in Paris, and launched her own eponymous fashion house in 2001. In addition to her celebrated eye for design, she has been an advocate for animal rights (“a lifelong vegetarian, she has never used leather, feathers, skin, or fur in any of her designs since day one—a revolutionary stance, then and now,” a mission statement reads) as well as issues of sustainability regarding materials and manufacturing. For her Spring 2021 collection, she collaborated with artists on an “A-to-Z manifesto” that pairs each letter in the alphabet with a progressive idea (A for Accountable, V for Vegan, and so on).

One of those artists is Sheila Hicks, who studied with Josef Albers in the 1950s and in the decades since has created sculptural artworks using fabrics and fibers as well as various methods of weaving, knitting, knotting, and braiding. Her work appeared in the 2017 Venice Biennale and the 2014 Whitney Biennial, and her reputation has grown alongside rising recognition of textile and fabric art, for a time underappreciated as a matter of craft. Hicks’s solo exhibition “Thread, Trees, River” opens at the Museum of Applied Arts (MAK) in Vienna in December and runs until mid-April 2021. For the “A-to-Z manifesto” project with McCartney, with whom she first collaborated in 2019, Hicks reinvigorated the designer’s classic Falabella handbag.

From London and Paris, respectively, McCartney and Hicks joined ARTnews for a videoconference in September to talk about sheep, mindfulness in fashion and art, and working together as colleagues and friends.

Sheila Hicks adorned Stella McCartney’s iconic Falabella handbag with dangles of color as part of the designer’s “A-to-Z manifesto.”

Courtesy Stella McCartney Ltd.

ARTnews: What are your earliest formative memories of experiencing art?

Stella McCartney: My grandfather was a lawyer who represented Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, Yves Klein, Robert Motherwell, and many of the great Abstract Expressionists. He would swap his time for their work and ended up having one of the largest private collections of Abstract Expressionism in the world. But it was all from love—every single part of it was passion and pure affection for art. My grandmother actually thought he was crazy and would shout at him when he would come back with another piece of art. When I was small, my early memories would be of going into his apartment in New York, where he had many Joseph Cornells. He was great friends with Cornell. As a child, I remember there was a low shelf in his library with all of these Cornell boxes lined up. He had extraordinary work on the walls, but it was the Cornells that really captured my attention because they were so childlike and playful.

Sheila Hicks: I’m going to do a fast-forward and say that when I was in London making a show a few years ago, the director of the gallery said, “There is someone I want you to meet who I think you will like and appreciate.” That was Stella. I went to her showroom, and the first thing she talked to me about were her sheep. I am known as sort of a consultant and a problem solver. So I knew why I was there: they wanted me to do something about these sheep. To me, it was great because it was something concrete. When you meet someone for the first time there’s a lot of small talk before you can get into some kind of substance of any kind.

McCartney: I don’t think we’ve ever had small talk, you and I.

Hicks: As I remember you said, “People are not ordering or wearing the scratchy or heavy wool as much as they used to. I raise sheep out in the country and I am very worried about their future.” I loved the idea of having to be concerned and occupied about the future of these sheep.

McCartney: I have a few sheep. They are called Itsy-Bitsy, Teeny-Weeny, and Yellow Polka. I haven’t got Dot and Bikini. They grow old gracefully, and they are completely organic—and every summer we sheer them so I have all this wool. My mother and father also had tons of sheep. We never killed them so they would always live a long, healthy life. And the wool we would weave into Native American–style rugs and blankets and things. I got the wool woven into some yarn and I made a sweater—you could smell the lanolin so heavily, and it literally could stand up on its own. It was so rough and tough, hard-core wool. So, yes, that was my project for Sheila: I would love a piece by you with my organic sheeps’ wool. We are yet to do it. Every couple of weeks I’m like, What’s going on with my sheep wool?

Hicks: I keep thinking you think I’m going to make it into something wearable.

McCartney looks: A for Accountable, at left, and Z for Zero-Waste.

Courtesy Stella McCartney Ltd.

McCartney: But Sheila, you were asked what is your first memory of art. I want to know!

Hicks: You make automatic associations. For me it is sheep.

McCartney: Ah, I love you! I’m disappointed with myself that I answered it so straight-on. But we have a connection through your great heritage with Josef Albers. My grandfather was his representative, and he had art by Albers lining his stairway—millions of different colors of Albers all the way up. You knew Albers also and hung out with him…

Hicks: I don’t know if you would call it hanging out. I was under his tutelage or his reign at Yale. I went and studied painting with him before you were on the block.

McCartney: Am I right in thinking you were the first woman?

Hicks: No, but there were very few. You could count them on your fingers, with maybe toes from one foot. Albers was a strong personality and was not nuanced in his human interactions. He was [nuanced] in his painting. But in his teaching and confrontations with his students and the people who depended on him, he was rather blunt. It was I think partly due to his difficulty in handling the subtlety of the English language when he came to America from Germany. He would go straight to the point. The punctuation almost was at the beginning of his sentences. Exclamation point—straighten up and listen because here it comes! He more or less took over my life when he saw that I understood and was sensitive to color. He would give me tasks. He would come in and say, “Girl…”—he couldn’t remember my name—“Girl, do this, do that.” Then one day he came in and said, “Girl, go down to the office and sign the papers I left for you—I’m sending you to Chile.” I went to the library and looked up on the map where it was.

ARTnews: Why Chile?

Hicks: He was on a committee that was selecting candidates for Fulbright scholarships. He had a connection to Chile. He had been there himself. He liked it and had set up a kind of annex of his teaching methodology in Santiago.

McCartney: You are unlike Albers in that you react very instinctively and emotionally to what is happening around you. You are not at all Germanic in the way that you approach things. Everything is sensory in the way in which you work. You’re spirited and you have light all around you—you are joyous. For the record, when we first met, I kind of stalked Sheila. I’ve always been a huge admirer and, in the fashion industry, she has been hugely influential. I’m not sure if she even knows that or if she chooses to acknowledge that she has been a massive influence on many designers. I’ve seen Sheila Hickses on the runway, and I know that she has inspired my work. So I stalked her and she very kindly took my meeting.

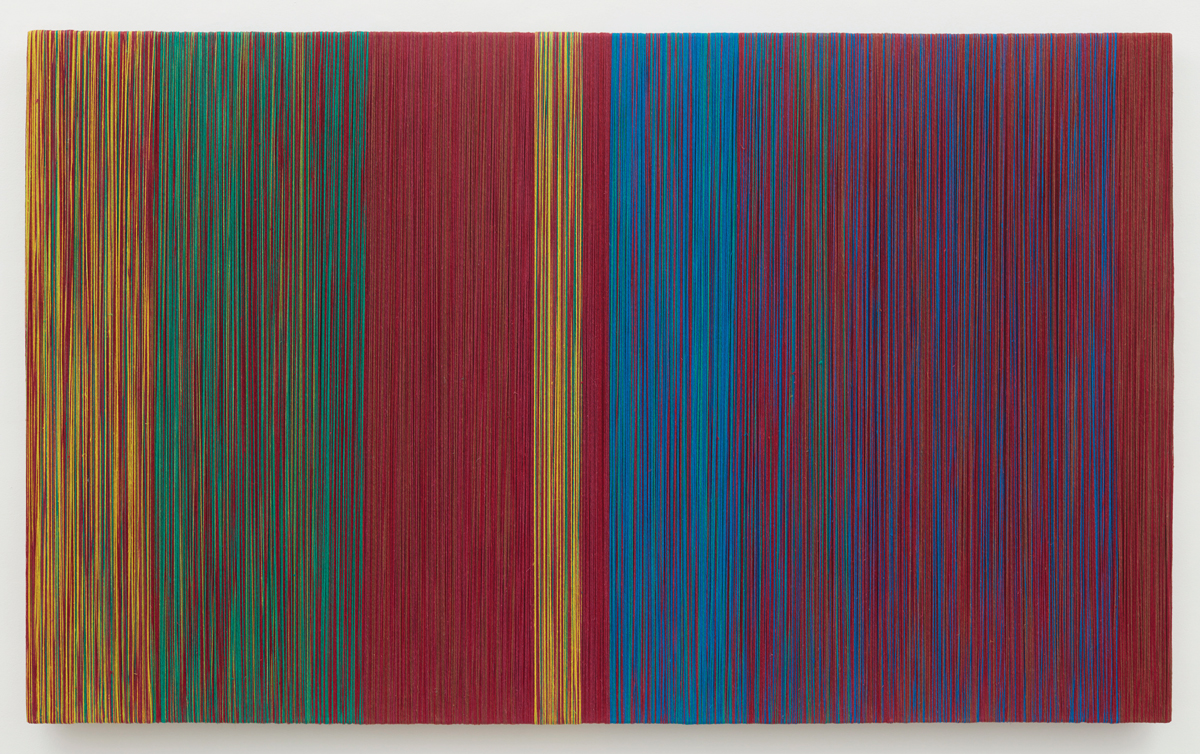

Shelia Hicks, Jardinet, 2018.

Courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York.

ARTnews: What is most significant about Sheila’s work in the context of fashion?

McCartney: What is extraordinary is the contrast of color. There are many reasons I’m so drawn to her work, but I identify the most with her use of color. She put a piece around my neck and we walked the streets of Paris….

Hicks: We walked out of the courtyard. We went through the gate. You were wearing a beautiful…

McCartney: Paris tweed.

Hicks: And everybody on the cobblestone path stopped. Their mouths dropped open and they turned as we walked by, and I thought, I think we are on to something. I think we are OK. We walked into a café and the guy who was jerking the coffee kept making mistakes—he made three coffees before he could get one right, because he was only watching you.

McCartney: Sadly, I think it was your work, Sheila, and not necessarily me.

Shelia Hicks, Bâoli, 2014.

Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York.

Hicks: He was trying to figure out who are these people and what are they doing? And I thought, This is real life. If we can get along like this, we could have a hell of a good time. We could be spontaneous. We could figure out what might be interesting and what is a waste. In the fashion industry that you lead…

McCartney: There is a lot of waste. There’s so much waste that every second there is a truckload of fast fashion either buried or burned. We are like-minded in our dislike of excess. We find it vulgar and upsetting. Tell me about how you work and how you have changed in the way in which you work. When we collaborated together, you made these paperclip earrings that became about waste and the charm and beauty in things that you glance over every day and take for granted. I could see your eyes go around the room and pick up things to create with. You took a measuring tape and sat in the back of the studio while we were doing fittings, and you wove a necklace out of the measuring tape and put it around my neck. Do you remember? I asked you to sign it to me. It was my first Sheila Hicks. But I came home the next day and my cleaner had very kindly taken it apart and wound it back up into a measuring tape again!

ARTnews: What do you two like most about working with one another?

Hicks: I’m going to go straight to something very recent, when you sent over a messenger from your Paris workshop with a big package to our studio. It was unannounced. They plunked it here in the midst of all our mess and, of course, whenever your things come in, they’re so beautifully packaged that we take good care of them. It is almost like in Japan, where the package is as important as the contents. So I was already alerted to pay attention.

Looks from a collaboration between Stella McCartney and Shelia Hicks on the runway for a Winter 2019 collection.

Courtesy Stella McCartney Ltd.

ARTnews: What was inside?

Hicks: We opened it and there was this series of handbags, and I wondered, What’s this all about? It was typical of Stella, sort of like, You figure it out—I’m bringing these over and dumping them in your studio. And this was obviously a fortune of precious handbags. But they were all wanting something. They wanted color. You talked before about seeing your grandfather and Albers color flashes all up the stairway. Now I’m going to switch and say that, when I walk into any given situation or place, I look for the object that is a tip-off of what a person has chosen to represent themselves. What is the object or thing that they have selected? If you start to see that, you’re going to see a conversation that could go in any direction. Oftentimes if it is a woman, I look at the handbag. I ignore jewelry because a lot of times jewelry is just to impress people or something that someone has given them or that they have bought for status. But handbags—when you dumped them in my studio, I thought, I’ve got to make something that is interesting, because there are going to be all kinds of personalities who walk into your shop or into your orbit to look at an assortment of handbags. They are going to choose one, and it is going to be their toy, their mascot, their daily companion. We can make some kind of interpretations and statements with colors that people are repelled by or attracted to.

McCartney: I feel like you use more color now than you have in the past. Would you say that I’m right in that?

Hicks: Not when I am making exhibitions.

McCartney: When you have little playful projects, do you feel that color is more appropriate?

Hicks: Well, I’m a task person. When people assign tasks, I try to figure out what the task is.

McCartney look: Y for Youth.

Courtesy Stella McCartney Ltd.

McCartney: Let me tell you a little about the bags getting dumped with you. At the beginning of lockdown, I had already started my spring collection and I was again coming back to the idea of waste and trying to be a more sustainable and conscious person in the fashion industry. I had said to my team that I really did not want to order any new fabric. I wanted to reduce what I produce this season. I wanted to focus on being more sustainable and more mindful, and to look at how we could go about that. Then came this idea of an alphabet. Every letter had a word associated with it, like a manifesto. A is for Accountable, B is for British, C is for Conscious, etc.

ARTnews: How did you choose Sheila to work on the letter F?

McCartney: F is for Falabella, a classic bag that we created. Sheila’s art is never going to get thrown away. It is so mindfully, beautifully crafted that it will be there for life and will get passed down from generation to generation. When I design, I try to create things that people won’t want to throw away—that they can either gift or hand down or resell. This is a bag that has been with us for a long time that people love. It has a softness to it. It has a hardness to it. And it is vegan, with recycled lining that is made out of ocean plastic waste. We are very proud of this bag, and I wanted Sheila to reinvigorate it with her own twist. She could adorn it or interrupt it to make individual pieces that could become even more cherished, even more loved and valued.

ARTnews: What was her immediate reaction like?

McCartney: She was kind of hesitant. What I love about Sheila is that she’s not here to BS anyone, and she was like, “I don’t get it. I don’t understand.” But then she brought new life to it.

Hicks: I tried take this coveted object and particularize it in some memorable way without making it less nice. How do you take a Stella McCartney bag and make it better? You have to be culottée to do that—in French that means you have to have balls. You don’t want to make it worse and you can’t ruin it, but how are you going to particularize it? Maybe by adding a sense of humor to it. In these times, I think that is one thing we all need.

McCartney: Does color add a sense of humor?

Hicks: Yes, definitely. Even when they bring food to you on a table, people notice if it has some color.

McCartney: Do you find it tiring seeing everything? Has it ever been a problem for you? I see you seeing everything—your eyes dart around the room, almost like a computer.

Hicks: It’s an advantage, believe me, not a disadvantage.

Shelia Hicks, Linen Contained, 2003.

Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York.

ARTnews: Stella, why was it important for you to work with artists on your latest collection?

McCartney: I wanted to assign each piece a different meaning. Z, for example, is for Zero Waste, and for that piece I used strips we saved. In the fashion industry we create our own prints, and most of the houses burn or bury leftovers. They don’t sell it or give it away because it is their own individual print and they don’t want anyone else to have it, whereas I save them because I can’t bear the thought of throwing them away. What I did was take what I had sitting in a warehouse and make a zero-waste dress.

Also, while creating this collection, I was really conscious of my community of friends during lockdown. Most of my friends are artists. I was isolated on my own, reaching out to my artist friends and thinking this was no different [from how artists] work. For my process, there are usually lots of people in the room from day one. So I thought I would love my circle of great artist friends to visualize these letters and words so it wasn’t just me alone. I wanted to bring artists in to create another layer of recognition.

Sheila Hicks, L’encinte, 2018.

Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York.

ARTnews: Sheila, how do you look at or think about fashion?

Hicks: Before I even see a dress, I touch it. I close my eyes and touch it, because I know it is going to touch my body. To get the maximum out of the minimum, you have to have beautiful material. And then from the material, move to the color and the cut, the tailoring, the draping. That’s my sequencing. I don’t start with color. I start with tactility.

McCartney: I start with texture too. In the design process we have to choose our fabrics first.

Hicks: We should overprint on top of the old prints—make a collection of printing on printing.

McCartney: I’ve got you, girl! We should do a whole other project.

Hicks: I went into a printer’s workshop where they were printing one of my books, and I saw in the trash all the pages they threw away because they were misprinted. We recuperated all of them and made a book out of the mistaken pages.

McCartney: I want one of those! Do you find it hard to tell the story of your work? For me there is so much depth to how I work in fashion—not just the design but the sourcing and being environmentally conscious of our fellow creatures—but I find it hard to tell that story. Do you feel people need to know the story of your work—or is that irrelevant to you? You know, the little piece of paper on the museum wall that tells your story?

Hicks: You have to alert their curiosity. In this digital age, everybody is so full of knowledge, awareness, and interactive communication that there are know-it-all characters who consider themselves critics of everything. I think you’ve got to find a way to puzzle them and stop them dead in their tracks, so they say, “Oh my god, I don’t get it, I don’t know what this is. But it is really interesting…”

McCartney: One of the reasons I wanted to get artists involved is because I feel like something critical to what we do falls away. I need to explain to someone that my shoes are vegan and they don’t have animal glue in them. I want them to notice but also not to notice, and I’m different in that, in a lot of ways, I want to erase the norms of the fashion industry. I want it not to be noticeable that you haven’t got a crocodile bag or leather bag, but I want to replace a very destructive and harmful side to the industry that I’m in.

Hicks: I think you are more a missionary and I’m more of a troublemaker.

McCartney: I’m a troublemaker too. That’s why we like each other.

Sheila Hicks, Safe Passage, 2014-15.

Courtesy Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York.

ARTnews: Sheila, the level of recognition and regard given to art made with textiles has soared in recent years. How do you feel about that at this stage in your career?

Hicks: What street are we going to walk down? Are we going to walk down the textile street or the art street or the design street? What I do is so off the wall that people have a hard time putting it into a category. Just when somebody wants to talk about it as art, you’re going to have 10 people shake their finger and say, “C’est très mignon mais c’est pas de la tapisserie”—it is very cute but it is not tapestry. When I came into orbit, tapestry was even higher in the hierarchy than painting. When Charles de Gaulle wanted to reestablish the prestige of France after the Second World War, what did he do? He sent abroad exhibitions of French tapestry.

Then we go into fashion and come to the whole beautiful industry of the silk weavers. And from there it is downhill. What were they doing in the United Sates? They were growing cotton down on the plantations—nobody was producing silk. I started at the bottom and was dismissed by everybody as not-art, not-textile, not-tapestry, not-design. It was decorative.

McCartney: How much has architecture informed what you do? Do you take interiors into account when you’re creating?

Hicks: Always. When I sit down someplace, I look around and see the space and the architecture and the light. And from there we move on. I don’t focus on the cup on the table until I’ve seen where I am sitting.

McCartney: What do you not like in a room?

Hicks: I hate to sit in a room and look at men wearing stupid neckties.

McCartney: [Laughs.] One of the artists that has joined you in my alphabet is William Eggleston. He always wears neckties.

Hicks: But are they fantastic neckties? They are guys’ one chance to make a statement.

McCartney: It’s the only gig they’ve got—I hear you. But he wears them very well. He pulls it off. It’s a good look.

Hicks: Imagine how exciting it was for me to go to Saudi Arabia in the 1980s and sit in a meeting where all the men were draped—every single one wearing head-to-floor textiles. It sticks with me because the guys were moving and changing positions and you’d see textiles moving all around the room. It was a real kick. These were not girls wearing short skirts and showing their legs and trying to call attention to their presentation. They were very modest and covered up, with mountains of material sitting there. It was a real thrill.

McCartney: It’s a definite flipside from what we are used to.

Hicks: I’ve been waiting…. Has anybody done a fashion show where people come in and walk the whole way in reverse?

McCartney: Oh, I don’t know. It’s very David Lynch. Probably—and if not, I’ll do it.

Hicks: I think we should.

McCartney: But what happens when they fall over and all of the models go down like dominoes, though? Are you going to take the blame when that happens?

Hicks: They’ll figure it out. It would be so nice to see things moving around the runway in reverse, like a film. You know how much fun it would be looking at a Charlie Chaplin movie in reverse? Or Buster Keaton? Get the guy who is putting the music on the runway to play in reverse. It will be fascinating.

A version of this article appears in the Winter 2021 issue of ARTnews, under the title “Stella McCartney + Sheila Hicks.”

Published at Fri, 20 Nov 2020 17:03:51 +0000