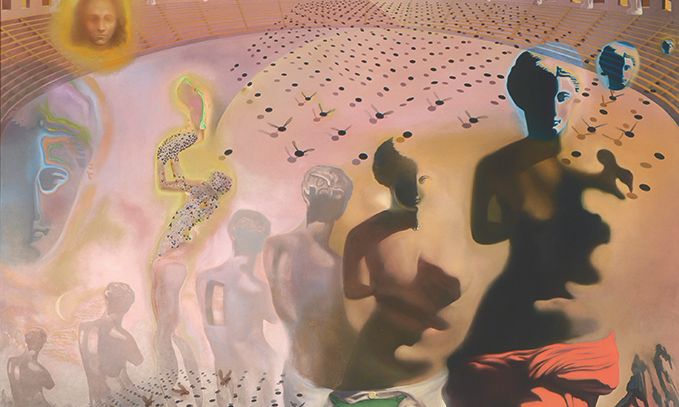

The Hallucinogenic Toreador (1968-70) by Salvador Dalí Courtesy of The Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, Florida, US

Art theft, as we know, is a big business, and it’s worth more than £5bn a year, putting it among the top international crimes after drug trafficking, money laundering and arms dealing. But stolen art used as collateral or bartered as a valuable commodity is rarely an isolated incidence. Something else is usually involved, be it drugs, weapons, money laundering, sex work or even human trafficking.

The Barcelona Connection is the first work in a series of crime thrillers that I am writing, set in the art world and with Benjamin Blake as the central character called in to investigate a crime scene as a work of art. Each book is planned to focus on a different artist, painting and city, and each work of art connects to a parallel, real-life crime—and I have to thank Dalí for setting me off on this book’s journey of double imagery and mistaken identity.

There are key moments that relate to these twin themes, and I use Dalí’s The Hallucinogenic Toreador (1968-70, above) as a “mirror image” of the discoveries made during the investigation of a murder and kidnapping.

Within hours of being sent to Barcelona to authenticate a possible study for Dalí’s Toreador, Blake is left stranded without his phone at a service station alongside a bloody corpse in the early hours of the morning. Blending the real with the surreal, he becomes the prime suspect in a politically motivated kidnap and murder, and he has 36 hours to clear his name and retrieve the painting.

The author Tim Parfitt alongside a statue of Salvador Dalí

Blake not only believes that investigating a crime scene is an art and not a science, but that every crime scene can be viewed as a work of art. The forensic scientist becomes the connoisseur, drawing conclusions from overlooked details, clues or traces.

I chose The Hallucinogenic Toreador, with its double image of a bullfighter who is “invisible” until you see that the repeated depictions of the Venus de Milo also portray his facial features, because it is a mirror image of the “invisible” or missing kidnap victim in my story. I learnt about Dalí’s obsession with the focal point of the painting through my conversations and correspondence with Joan Kropf, the former chief curator at the Salvador Dalí Museum in Florida. The Dalí Foundation in Figueres also helped with my research, and further information was provided by the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, specifically on the forensic examination of paintings.

Dalí described the Toreador as “all Dalí in one painting”. Dalí had a brother, also called Salvador, who died before the artist was born. The ‘invisible’ bullfighter, about to die, represents his dead elder brother. Dalí’s parents liked to think of him as a reincarnation of his brother, seeing a close spiritual and physical likeness in their two sons. Being regarded, in the eyes of others, as someone else—and someone who was dead—was a problem that exercised a strong influence on the formation of Dalí’s character. That sense of “mistaken identity” is an essential ingredient of the book.

• Tim Parfitt, The Barcelona Connection, Maravilla Press, 502pp, £10.99 (pb)