[ad_1]

By Jim Vertuno, AP Sports Writer

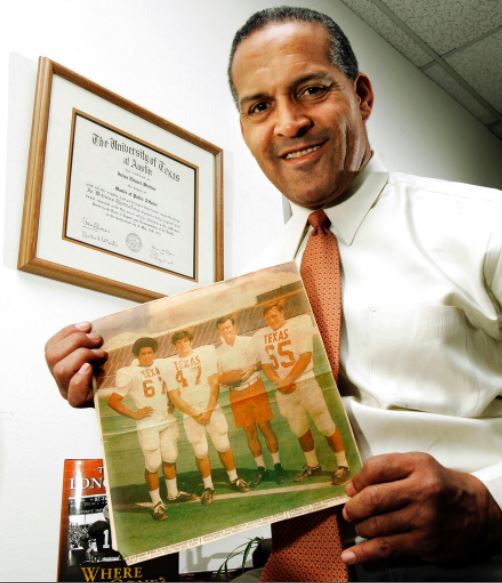

Julius Whittier once remarked that attending the University of Texas and playing football opened up a larger world for him. It could be said Whittier helped open the university to the world.

Whittier was the Longhorns’ first African-American letterman, making his debut in 1970, one season after Texas fielded the last all-White national championship team in the history of college football. He starred for two seasons at guard before switching to tight end as a senior in 1972, a season in which he caught every touchdown pass the Longhorns threw.

“And I caught it in the (Texas) A&M game,” he said in the 2007 book “What It Means to be a Longhorn.” ”We had one touchdown pass the entire year.”

Whittier died Sept. 25 at age 68, the school announced Sept. 27. No cause of death was given, but Whittier had been battling Alzheimer’s disease. In 2014, his family sued the NCAA on behalf of college players who suffered brain injuries. The case is still pending.

The school’s Board of Regents dropped its ban on Black players in 1963 but integration was painfully slow and difficult. A few Black players signed with the Longhorns over the next several years, but none stayed long enough to make the varsity in an era when freshmen were ineligible to play under NCAA rules.

Texas recruited Whittier out of San Antonio and his parents were scared of what might happen to him in Austin.

“My dad was scared for me,” Whittier said in 2007. “He’d known some guys who struck off into ’White’ territory and paid for it with their lives.”

Whittier landed on a campus of nearly 35,000 students and only 300 were Black. He was a star on the freshman team, and Texas made Whittier available for interviews before his debut season.

“I’m a loner up here,” Whittier told the San Antonio-Express News in early 1970, noting his coaches were treating him well but hinting at having problems with some of his teammates.

“Texas seems to recruit a lot of boys from small towns, and most of them have small minds just like their fathers,” he said. “They never think about the things that are happening in this country. You never hear them talk about Vietnam or racism. If you want to know the truth, the only people I’ve met that I can really talk to are the longhairs or hippies. They are really concerned about things like ecology and the war. I’m concerned about those things, too.”

A few months later, a group of sportswriters covering the Southwest Conference looked into his social life. The lead of a Sept. 8, 1970, article by The Associated Press noted that “Whittier, Texas’s black offensive guard, is rooming with a white player and occasionally dates white girls.”

The story noted that Whittier said no one at school had said anything to him about the dating.

“I don’t think it’s anything unusual. Well, unusual, but not abnormal,” Whittier said then.

Texas senior halfback Billy Dale was Whittier’s roommate that season; Whittier’s previous roommate, another Black player, had left school. Coach Darrell Royal had asked Dale and two other seniors to consider rooming with Whittier, Dale said.

“Coach Royal wanted someone to help look out for him,” Dale told the AP on Sept. 27. “I volunteered. We learned a lot from each other. He just added a depth to who I was. He made me a much wiser individual about racial relationships.”

Whittier played in the 1970 season opener against California. Texas won three Southwest Conference titles from 1970-72. The Longhorns were 28-5 over that span, 20-1 in the SWC.

Perhaps frustrated early by his role as a trailblazer, Whittier seemed to embrace it by his senior season when he said in an interview he went to Texas in part to change its culture: “I wanted to see if the myth about UT’s racism was true. If it was, I wanted to see what I could do to change it.”

Whittier earned an undergraduate degree in philosophy and a law degree from Texas. He went on to be a criminal prosecutor in Dallas.

Whittier’s success opened doors between Texas and Black athletes. In 1971, Texas recruited the top player in the state in running back Roosevelt Leaks. By 1974, it had signed Earl Campbell, who would win the Heisman Trophy in 1977 and go on to a Hall of Fame career in the NFL.

“I am so proud of Julius,” Dale said. “His legacy is the fact that he was an individual who was smart enough and confident enough to come to Texas and challenge the university.”

[ad_2]

Source link