Adventures with Van Gogh is a weekly blog by Martin Bailey, our long-standing correspondent and expert on the artist. Published every Friday, his stories range from newsy items about this most intriguing artist to scholarly pieces based on his own meticulous investigations and discoveries. © Martin Bailey

Van Gogh is arguably the world’s best-loved artist, and he is certainly among its most popular. Yet during his own lifetime, he was largely ignored and failed dismally to sell his work.

So why has Van Gogh become such a global celebrity? Of course it’s the art, but equally important is the story of his life. Any judgement is personal, but I suggest ten reasons why we love Van Gogh. Five are about his trailblazing art, five about his remarkable life.

While Van Gogh’s early Dutch pictures are painted in dark, gloomy tones, his later works done after his move to France positively burst with colour. The change came when he arrived in Paris in 1886, aged 32, and discovered the work of the Impressionists and plunged into their milieu. This opened his eyes—and transformed him into a consummate colourist. Two years later, when he painted Cottages in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, on a brief trip to the Mediterranean, he wrote that the sight of the coast had made him realise that “the colour has to be even more exaggerated”.

Van Gogh’s Cottages in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer (June 1888)

Kunsthaus, Zurich

Van Gogh’s brushwork was highly innovative, often employing thick layers of paint in near-parallel lines. For instance, in Starry Night (June 1889) the brushstrokes of his cypress trees reach upwards, the distant hills are formed of angled marks and the swirling lines of the night sky create a disturbingly turbulent effect. For this painting, Vincent told his brother Theo he had used “thick impastos” of white paint, then added colours on top.

Van Gogh’s Starry Night (June 1889) Museum of Modern Art, New York

Provençal landscapes are among the most beautiful in France and Van Gogh’s subject matter holds great attraction for those who, like the artist, are nature lovers. A Wheatfield, with Cypresses (September 1889) epitomises the artist’s vision of the captivating countryside. A golden band of ripened wheat ripples across the foreground, several olive trees are dotted in the field, a pair of dark cypresses rise up and in the background lie the dramatic hills of Les Alpilles (the little Alps). Van Gogh’s paintings transport us to this enchanting landscape.

Van Gogh’s A Wheatfield, with Cypresses (September 1889) National Gallery, London

Van Gogh’s exaggerated rising or setting suns are symbolic, not literal. They either represent the dawn of a new day or the ending of one that is passing. Introducing these unworldly discs into his landscapes also creates striking visual effects. They stun the viewer and allow the artist to explore his favourite colour: yellow.

Van Gogh’s Pollard Willows at Sunset (February 1888) Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

Van Gogh was an Expressionist, although it would be around two decades later that the term came into use by art critics. He distorted reality to evoke moods and express ideas. For instance, in Portrait of Dr Paul Gachet, the artist set out to convey the doctor’s character and personality. And in his series of Sunflower paintings, Van Gogh lends character to the flowers, rather than striving for botanical accuracy. Through his expressive technique, he set the scene for the development of Modern art in the 20th century.

Van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr Paul Gachet (June 1890)Private collection

Van Gogh had a truly amazing story. As a trainee dealer in The Hague, London and Paris, he discovered the commercial world of art. A few years later, after he had been sacked, he lived in abject poverty as a preacher in a Belgian mining community. Van Gogh then set out to teach himself to draw and paint. In The Hague, he lived with Sien Hoornik, a woman who had earned her living in the streets. After moving to Paris, he stayed with his brother Theo in Montmartre, discovering its famed nightlife with fellow artists. Two years later he set off for the Provençal town of Arles. He later mutilated his ear, presenting the severed flesh to a woman in a brothel. He recuperated for a year in a mental asylum outside Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. Aged 37, in a moment of desperation he shot himself, in the village of Auvers-sur-Oise. What a difficult life, what a tragic ending.

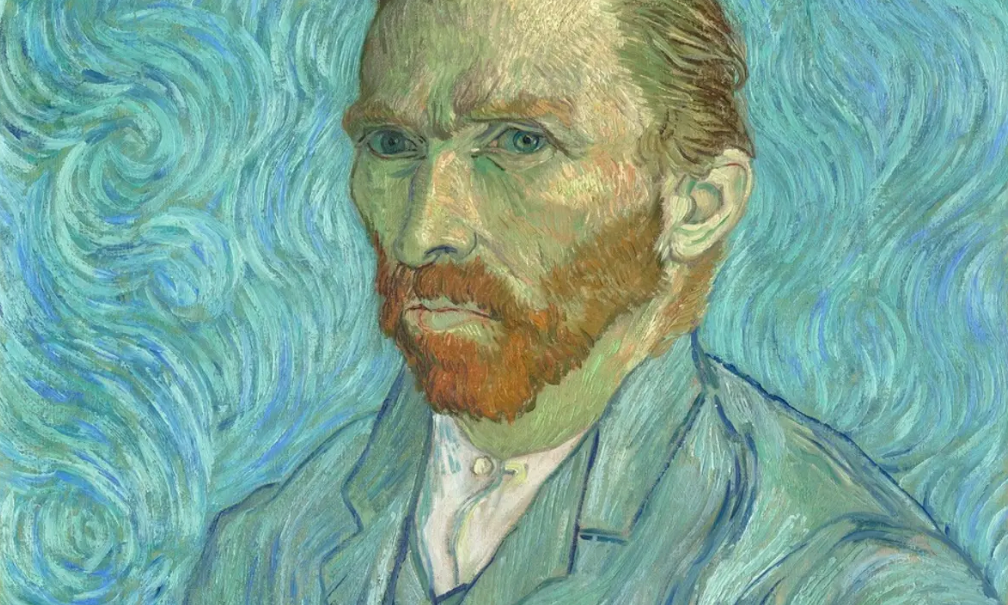

Van Gogh’s Self-portrait (September 1889) Musée d’Orsay, Paris

While living in Paris Van Gogh met many of the artists who are now the big names of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, including Camille Pissarro, Edgar Degas, Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec – and, most importantly (and interesting for us), Paul Gauguin. Eight months after Van Gogh left Paris, Gauguin joined him in the Yellow House in Arles. Although both were avant-garde painters, their personalities clashed and the collaboration ended disastrously, when Van Gogh mutilated his ear. Their time together in the autumn of 1888 would form the dramatic centrepiece of Lust for Life, the influential novel by Irving Stone (1934), which was later turned into a highly successful film (1956).

Van Gogh’s Self-portrait dedicated to Paul Gauguin (September 1889) Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts (bequest Maurice Wertheim, Class of 1906)

Once Van Gogh had decided to become an artist, nothing held him back. His whole life revolved around art, which meant surmounting a constant onslaught of challenges. Financially, he was totally dependent on an allowance from his brother Theo. But most difficult of all was his unstable mental health, particularly in his last two years. The fact that he never lost his creativity still provides a great inspiration to those today who face challenges themselves.

Van Gogh’s Self-portrait as a Painter (December 1887-February 1888) Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Van Gogh’s letters are the most compelling of any artist, of any period. They reveal so much about both the development of his art and his personal life, almost representing a diary. His 820 letters have been translated and annotated by the Van Gogh Museum, which publishes them on its website. Without these letters, we would know vastly less about his career. For us, they truly bring his story to life.

Van Gogh’s letter written in English to the Australian artist John Peter Russell, around 17 June 1888, Arles Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York (Thannhauser Collection, Gift, Justin K. Thannhauser, 1978)

Van Gogh only managed to sell a single identified painting in his lifetime, The Red Vineyard (November 1888). But now he is among the most valuable artists ever, with Orchard with Cypresses (April 1888) being auctioned for $117m in 2022. Van Gogh’s posthumous reputation gives us all hope of eventual success in whatever we are striving to achieve.

Van Gogh’s Orchard with Cypresses (April 1888) Christie’s

Martin Bailey is the author of Van Gogh’s Finale: Auvers and the Artist’s Rise to Fame (Frances Lincoln, 2021, available in the UK and US ). He is a leading Van Gogh specialist and investigative reporter for The Art Newspaper. Bailey has curated Van Gogh exhibitions at the Barbican Art Gallery and Compton Verney/National Gallery of Scotland. He was a co-curator of Tate Britain’s The EY Exhibition: Van Gogh and Britain (27 March-11 August 2019).

Martin Bailey’s recent Van Gogh books

Bailey has written a number of other bestselling books, including The Sunflowers Are Mine: The Story of Van Gogh's Masterpiece (Frances Lincoln 2013, available in the UK and US), Studio of the South: Van Gogh in Provence(Frances Lincoln 2016, available in the UK and US), Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum (White Lion Publishing 2018, available in the UK and US) and Van Gogh’s Finale: Auvers and the Artist’s Rise to Fame (Frances Lincoln 2021, available in the UK and US). Bailey's Living with Vincent van Gogh: the Homes and Landscapes that Shaped the Artist (White Lion Publishing 2019, available in the UK and US) provides an overview of the artist’s life. The Illustrated Provence Letters of Van Gogh has been reissued (Batsford 2021, available in the UK and US).

To contact Martin Bailey, please email [email protected]. Please note that he does not undertake authentications.

Read more from Martin's Adventures with Van Gogh blog here.