[ad_1]

Portrait of Takashi Murakami in the exhibition “Heads↔Heads,” 2018, at Perrotin New York.

GUILLAUME ZICCARELLI/©2017 TAKASHI MURAKAMI/KAIKAI KIKI CO., LTD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED/COURTESY PERROTIN

In 1980, when the Japanese artist Takashi Murakami was 17 years old, he saw the anime movie Galaxy Express 999, about a boy finding his way as an astral traveler. “It was like my spirit was flown away into outer space,” he remembered. “This was around the time that Japan went into a bubble economy—there was a festive mood, but as an adolescent, I was wary. In order to escape that anxiety, there was sci-fi.”

Today, at 56, Murakami calls Galaxy Express 999 his favorite movie—and claims it resonates now as it did back then. “There’s something similar to that mood right now,” he said of uneasy feelings around the globe. For this current age of anxiety, however, Murakami has been most directly channeling a different influence: Francis Bacon, the late British painter of deeply unsettling and psychologically entangled portraits.

In April, Murakami spoke about his cultural references of choice at Perrotin gallery on the Lower East Side of New York, where his exhibition “HEADS↔HEADS” has taken over three floors since April for a show that continues through June 17. The exhibition features a series of acrylic portraits sharing the title “Homage to Francis Bacon,” all of them swirling works that filter the great painter’s desperate humanity through Murakami’s trademark sugar-coated manga palette.

“I feel that he was probably unbalanced, and I can sympathize with that,” Murakami said of Bacon. “I’m really drawn to his work, in which bodies and faces are distorted. His surrealistic way of thinking resonated with me, so I decided to study him more and try to follow the way his brain might work.”

Though their aesthetics might not seem to have much in common, Murakami’s recent work isn’t the first for which he turned to Bacon. “A long time ago I made one piece trying to imitate his work with my character Mr. DOB,” he said of his iconic mouselike hallmark with big ears and bulging eyes. “It was a time when I wasn’t really selling work so much, but it sold right away.” A decade went by before he revisited the same process and began creating the work in his latest gallery show.

Once one of the most-quoted artists in the world—during a mid-2000s global art-star prime featuring glamorous exhibitions and crossover work with the likes of rapper Kanye West—Murakami has stepped back from interviews over the past few years. But he decided to talk in New York. With the aid of a translator, he spoke in a quiet, raspy voice, pausing occasionally for sips from a glass of orange juice. His long salt-and-pepper hair hung over a yellow flannel shirt worn with cropped cargo pants and a clutch bag secured around his chest with a red strap bearing the words “Off White”—the fashion label founded by Murakami’s latest collaborator, Virgil Abloh, who was recently appointed artistic director of menswear at Louis Vuitton.

Murakami credits the younger Abloh with inspiring him to talk again. Before the two began their collaboration, which has so far included designs for Louis Vuitton products and a shared exhibition at Gagosian gallery in London titled “Future History,” Murakami had been declining interviews “because I felt that I was always asked the same questions and was always saying the same thing,” he said. “I would get depressed and think, I’m an artist—I should just focus on making art.” Abloh took a different tack. “I would watch him do interviews from morning to night,” Murakami said, “and then we’d have dinner and he’s still earnestly talking about his ideas.”

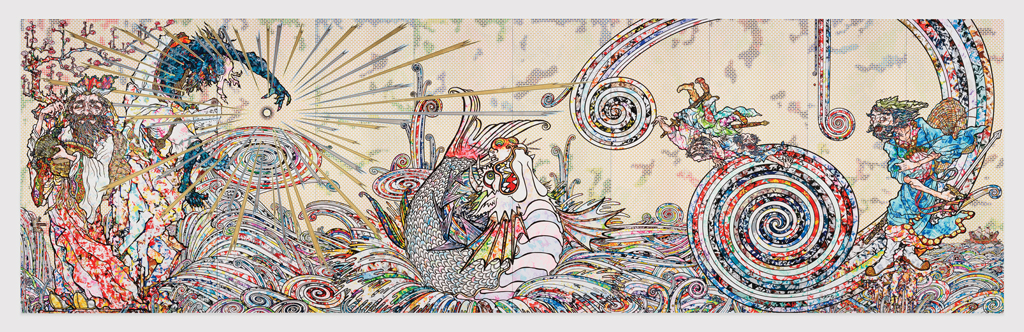

Takashi Murakami, Transcendent Attacking a Whirlwind, 2017, acrylic, gold leaf, and platinum leaf on canvas mounted on wood panel, 300 x 1000 cm.

©2017 TAKASHI MURAKAMI/KAIKAI KIKI CO., LTD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED/COURTESY PERROTIN

A few days after his gallery opening, the Frieze New York art fair featured iconic Murakami artworks that figured in his decades-ago debut in the city. First shown in 1996 at the gallery Feature Inc. by the visionary dealer Hudson—the subject of a tribute at Frieze devoted to a career that ended upon the gallerist’s death in 2014—the Murakami works in the fair included three almost-identical statues, all of them girlish in the style of Japanese manga characters, looming in front of a tri-paneled painting, Rose Milk, that served as a minimalist backdrop. In a video interview posted online for the fair, Murakami said, “When I met with Hudson, a long time ago, I had no money and no connections. I had no confidence—but Hudson gave me confidence.”

Murakami found his way to a New York debut at Feature Inc. through a serendipitous interaction at a different art fair, in Japan. In the early 1990s, after the country’s economic bubble burst, he started experimenting with T-shirts. “I had a silk screen and would print it on the shirt and it would be $70—and on paper it would be $700,” he said. He was interested then—and remains so—in ways that changes in medium can make for changes in value.

In 1992 Murakami brought one of the T-shirts to Japan’s first contemporary art fair in Yokohoma, where he met Emmanuel Perrotin. Then age 25, his future dealer was trying to establish himself as a gallerist. “He came with just one suitcase and filled a room this big,” Murakami said, gesturing around Perrotin’s sizable downtown space. “Even though I couldn’t speak English and couldn’t really communicate, I had great respect for him. I was very moved.”

And Perrotin was likewise taken with Murakami’s work. “I had never seen an artist working with manga before Takashi,” the dealer said. “No one in America really knew manga culture yet, but I grew up with it.”

In 1994 Perrotin brought one of Murakami’s silk-screened shirts, with an image of a girl jump-roping with her own breast milk, to New York for the Gramercy Art Fair (which would later become the Armory Show), and it caught Hudson’s eye. Murakami recalled the late dealer saying to him, “Oh, you’re interested maybe in the human body transforming or morphing into something?”

Flash forward to the mid-2000s, when Murakami—who had by then joined the roster of Los Angeles gallery Blum & Poe before adding megadealer Larry Gagosian to his profile—became known, along with the likes of Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst, as a “business artist,” with huge studios, teams of assistants, and a prolific output of monumental artworks and commercial merchandise. His fame went on to transcend the art world. To date, Koons and Murakami are the only artists who have presented floats in the world-renowned Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade in New York, Koons with a huge balloon rabbit in 2007 and Murakami with a float version of Mr. DOB in 2010. (Murakami perhaps bested Koons by also appearing in the parade himself, bopping around in a flower costume.)

In additional displays of his marketable force, Murakami collaborated on commercial projects with Kanye West, for whom he designed an album cover, and pop star Pharrell Williams, as well as fashion designers like Issey Miyake, in a manner that continues. The same week as the opening of his current Perrotin show, the New York locations of the Japanese clothing store Uniqlo debuted 15 T-shirts and a plush toy that Murakami designed, based on the manga character Doraemon.

Alongside such commercial projects, Murakami has continued his work in fine art. The month before he was in New York, he had been in Paris at the Fondation Louis Vuitton for the opening of the group exhibition “In Tune with the World”, which includes his work through the end of August. In January, “Takashi Murakami: The Deep End of the Universe,” a show of large multi-panel works, closed after a nearly three-month run at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo, New York.

It was another recent exhibition, at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago last summer, that cemented Murakami’s renewed status as a star. The mid-career survey “Takashi Murakami: The Octopus Eats Its Own Leg” drew 205,000 visitors, the highest attendance ever for an exhibition at the museum—beating the previous record, set by an exhibition of David Bowie’s personal archive, by 12,000 attendees.

It was during the Chicago exhibition that Murakami met Abloh. Speaking about work he had done for Louis Vuitton, Murakami told Esquire magazine, “Virgil came to see me, and he told me that the reason he entered into this creative world is because he saw my collaboration with Louis Vuitton with the multicolored monogram. He didn’t really have anything to do with art, but he and his friend Don C. saw the window display at Louis Vuitton, and that’s how they got excited about art.” (He also told Esquire that at ComplexCon, where he was a committee member two years ago, he embraced his fans from a younger generation, including sneaker heads and, as he put it, “otaku—geeky-looking, Star Wars fan kind of people” with whom he identifies, being himself “basically a geek.”)

A few days before we met in New York, Kanye West, whose 2007 album, Graduation, featured cover art by Murakami, had set Twitter on fire with a flurry of tweets including some in favor of U.S. President Donald Trump. Among his politically incendiary postings was one promoting his upcoming album with Kid Cudi, in which he showed an image of anime-style drawings of himself and Cudi alongside the album title in Japanese script, accompanied by the words “Murakami vibes.” Displeased with the rapper’s ranting, Murakami told me that West is like the guy you fall in love with over and over again in high school—despite how much he lets you down.

Murakami’s work is so ubiquitous throughout various realms of culture that it’s sometimes hard to remember his beginnings in the art world, though he himself has not forgotten. He called Perrotin a “very hungry boxer making it out there with the spirit of never giving up,” fighting for the artists he works with and to expand an empire that now includes Perrotin galleries in New York, Paris, Hong Kong, Seoul, and Tokyo. An especially meaningful time between the artist and his dealer came after the financial crisis in 2008, Murakami recalled. “Emmanuel called me right away. He basically strangled himself by saying, ‘I’m going to support you throughout.’ I was really helped by him. My company almost went bankrupt, but I survived with his help.”

Their fortune has changed, and success has returned. Perrotin said that “HEADS↔HEADS” brought in 3,000 visitors its first day in New York, and the work—priced between $70,000 and $5 million—had all sold.

However much his stock rises, Murakami said he is still fascinated by the formative love of his youth: anime. One recent favorite is Made in Abyss, a series that starts with a group of kids looking for a treasure in a cave and turns into a dark tale about sickness and death. “It’s a very grotesque world,” he said, “but it’s depicted with cute Japanese anime characters, so it has an impact and it really moves you.”

But nothing can replace the impact of Galaxy Express 999. “There are great works that came after it,” Murakami said of his favorite film, “but, for me, what I saw when I was in high school is still guiding my life.”

A version of this story originally appeared in the Summer 2018 issue of ARTnews on page 40 under the title “Sci-Fi Art Guy.”

[ad_2]

Source link