[ad_1]

What’s that you’re asking? Another Monet show? While the Denver Art Museum is billing its current exhibition, “Claude Monet: The Truth of Nature,” as “the most comprehensive U.S. exhibition of Monet’s paintings in more than two decades,” myriad aspects of this protean Impressionist’s body of work have been surveyed in both broad strokes and minute detail over the past 20 years. You need more than two hands to count these presentations on your fingers. They include: Monet at Vétheuil: The Turning Point, Monet in Normandy, Monet: The Seine and the Sea, Monet and the Seine: Impressions of a River; Monet in Giverny: Landscapes of Reflection; Monet and the Mediterranean; Monet’s London: Artists’ Reflections on the Thames; Monet and Camille: Impressionist Portraits of His Wife; Monet and His Friends; Monet and the Birth of Impressionism; Monet: The Early Years; Monet: A Bridge to Modernity; Monet: Light, Shadow, and Reflection; Monet’s Impression: Sunrise, The Biography of a Painting; The Unknown Monet: Pastels and Drawings; and Monet: The Late Years. Whew!

As it is, curators have selected—and discussed in their respective catalogues—Monet’s art in ways that reflect a constantly evolving discourse. Some shows have stressed biography; others, his originality. His work has been approached formally, historically, philosophically. Even a touch of social consciousness has entered the picture: born in 1840 to a middle-class Parisian family, Monet was a poor, struggling artist who had difficulty putting food on his dinner table but ended up as a dear friend of the prime minister of France and the owner of a vast estate that employed full-time gardeners and an accomplished chef.

Because Monet, after a certain point, made works in series, you’d think it would be relatively easy to borrow his pictures. It isn’t. Some institutions won’t lend so as not to disappoint visitors expecting to find their favorites on view. And those willing to let other museums borrow their Impressionist treasures need to let their well-travelled works of art rest from time to time. With courage and conviction, Denver—and its co-presenter, the Museum Barberini in Potsdam, Germany, where the show travels next, after it closes on February 2—sought out unfamiliar, top-notch Monets for their extensive survey of landscapes and urban views made across seven decades. Rather than the usual suspects, you’re going to find lots of canvases from private collections as well as places as far-flung as Australia, Japan, Brazil, and Scotland.

Marunuma Art Park, Asaka

If someone mentions Monet, there’s a good chance you picture in your mind’s eye either the radiant gardens in Giverny that the artist painted during the last quarter of his long life or the bustling scenes he depicted in and around Paris early in his career. While the Denver show somewhat overlaps with “Claude Monet: Seasons and Moments,” the landmark exhibition MoMA curator William C. Seitz mounted in 1960, it stresses much more the artist’s peripatetic ways. From his home base—first, in Paris; later, in Vétheuil; and eventually, Giverny—the Impressionist travelled to a wide range of locales where he painted distinctive canvases. This survey includes pictures executed in the Netherlands, Le Havre, Vargeville, Norway, Belle-Ile, L’Etretat, Antibes, Rouen, London, and Venice. However, as you wander among the various sites depicted in different seasons and under a variety of weather conditions, you won’t get lost. The walls in each section change colors as you wind your way around the two floors of the show, moving from site to site. (It was organized by DAM’s chief curator, Angelica Daneo; its director, Christoph Heinrich; and the Barberini’s director, Ortrud Westheider.)

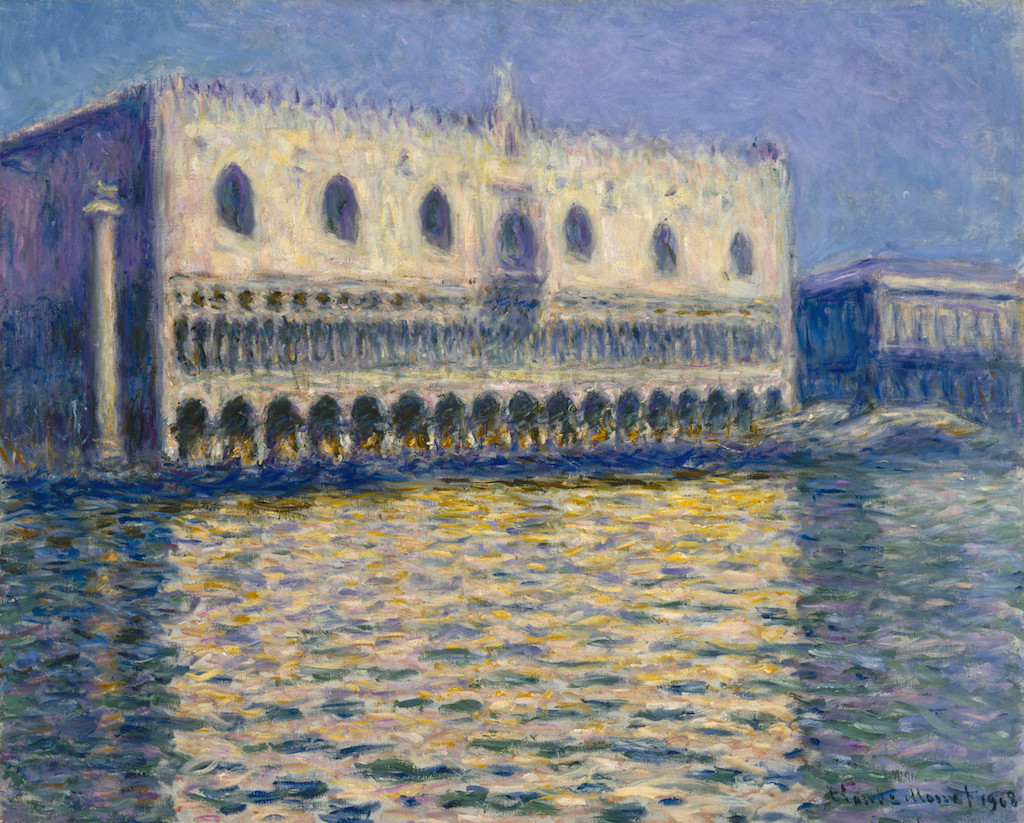

Monet skillfully portrayed the ineffable and the momentary. Scuttering clouds cross clear blue skies; sunlight is reflected in the blue waters of Venetian canals and French rivers. Steam rises from boats and trains. London bridges are cloaked in pea-soup fog; and the record-breaking cold winter of 1880 is witnessed as ice floes break apart in Vétheuil. These days, time-based art—made via computer, video, or performance—is front and center in the art world. But more than a century ago, Monet was constantly recording temporal events using traditional means.

The first section of the show offers gallery-goers several surprises. For starters, the curators have reunited canvases of the same Norman scene rendered in 1858 by Monet’s mentor, Eugene Boudin, and his student, who was 16 years younger. Monet later recalled, “If I became a painter, it is to Eugene Boudin that I owe the fact.” While Boudin’s landscape is accomplished, it verges on the generic. Long, lingering clouds in the blue sky emphasize the horizontality of the work; the treetops echo a more prominent green bush. Monet’s blue sky is more expansive and has fewer and fluffier clouds; the trunks of his tall trees in the background create a vertical rhythm that’s underscored by their reflection in the water in the foreground.

An unfamiliar night scene of the harbor in Le Havre, never before exhibited in the United States, occupies a nearby wall. It’s the same setting as Impression: Sunrise (1874), the Monet work that gave the movement its name. In this haunting piece, a series of circular dots create a pronounced band across the painting; magically, the lights also exist as shimmering reflections in the water. Given the rarity of the artist’s portraying the world after dark, it’s a lovely, unexpected view to encounter.

Since almost all the paintings feature no figures, it’s easier to recognize how Monet selected where he would visit. Not surprisingly, he often went to places where he could portray water variously. You’ll find pictures where it’s calm, turbulent, a narrow stream, a winding canal, a broad river, in winter and summer, a place where you might swim or row a boat or even ice skate. He painted masterpieces in places both urban and rustic.

The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

In Antibes, Monet foregrounded palm trees and portrayed snow-capped mountains in the distance. As for architectural monuments, he depicted a series featuring an echt Gothic cathedral in Rouen; then, slightly later Venetian palazzos; and even further along in time, the Gothic Revival Houses of Parliament of London. At the end of his life, he intently portrayed his Japanese garden, while other French artists were being inspired by Japanese prints.

As you move through the show, there’s a wonderful balance between subject matter and the ways it’s rendered. But at a pivotal moment during his late years, pure aesthetics take over. Swirling brush strokes, dabs of paint, and remarkable color choices were melded much more in the service of abstraction. Monet flirts with the properties of non-objective art. It’s a thrill to watch the artist in the 1920s, now an octogenarian, harness all the powers of his paint box. At 86, he would die in 1926.

As you become immersed in enthralling, dramatic views of the artist’s Japanese bridge, rose arches, peonies, and countless water lilies, you realize that “Claude Monet: The Truth of Nature” is telling the story of a long life lived to it fullest.

[ad_2]

Source link