[ad_1]

Malicious actors have plenty of tools at their disposal to spread misinformation and inflammatory rhetoric online, including by disseminating it through legitimate sources such as journalists.

A new report from the research institute Data and Society identifies the tools and tactics these actors use to manipulate media professionals and social media platforms into sharing misleading — or outright false — information.

The report, titled “Source Hacking,” describes an ecosystem of well-meaning journalists, bots, social media campaigns and those who want to spread bad information. As the 2020 election looms, journalists are already grappling with how misinformation has affected the election and every campaign talking point under the sun.

The study looks at four different techniques used in source hacking and suggests how journalists can be more vigilant about who they’re providing a platform for and what misinformation they may be inadvertently spreading.

Viral Sloganeering

Researchers Joan Donovan and Brian Friedberg define viral sloganeering as the “repacking [of] reactionary talking points for social media and press amplification.” They describe networks of people online who purposefully rework inflammatory talking points to make them more suitable for mainstream distribution. In turn, their talking points might make it to primetime.

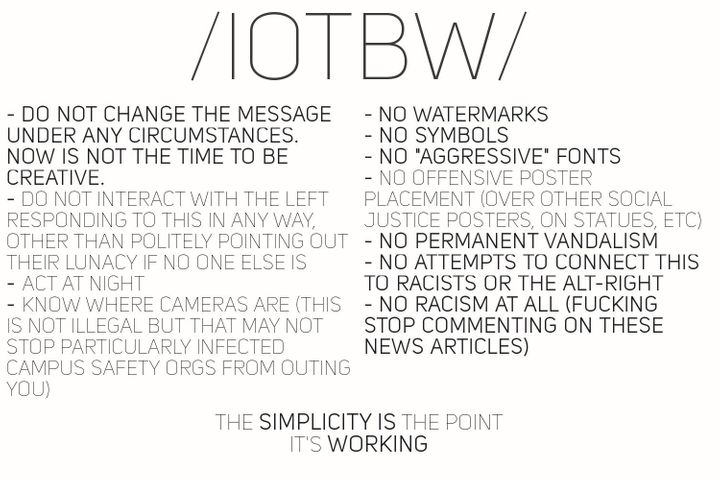

The report cites the “It’s Okay To Be White” controversy in which several news outlets uncritically reported on a popular racist slogan promoting “white pride.”

On right-wing message boards popular among white nationalists, users devised a plan to coyly spread flyers with the “It’s Okay To Be White” slogan in public places like college campuses, researchers said. Then, these users would revel in the ensuing news coverage that — critical or otherwise — helped spread their message.

“Journalists must also work to understand their role in an amplification network,” researchers wrote in Wednesday’s report. “[A]nd look out for instances where they may unwittingly call attention to a slogan that is popular only within a particular, already highly polarized online community.”

Leak Forgery

Researchers described leak forgery as any attempt to “prompt a media spectacle by sharing forged documents” that are intended to look like leaks from their political targets.

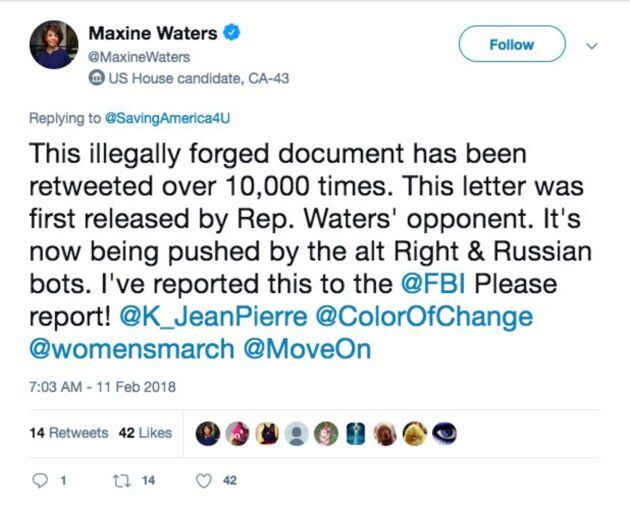

They cite a 2017 incident in which Omar Navarro ― the Republican challenger for a congressional seat held by Rep. Maxine Waters (D-Calif.) ― shared a forged letter that he said showed Waters accepting donations in exchange for allowing immigrants to settle in her district as conservative media and politicians were stoking fears about immigration.

Researchers said right-wing propagandists, bots, mainstream reporters and even Waters herself helped disseminate Navarro’s tweet and the forged letter by engaging with them.

To combat leak forgery, the report calls on journalists and social media users to check the validity of leaked materials, verify the source of those materials, and “seek numerous confirmations” from various sources when a claim is attributed to an anonymous person.

Evidence Collage

The Data and Society report defines an evidence collage as a picture “compiling a mix of verified and unverified information in a single, shareable image,” often used by conspiracy theorists to sanitize fake material by sharing it alongside legitimate info.

At the deadly 2017 white nationalist protests in Charlottesville, Virginia, neo-Nazi James Fields drove his car into a crowd of counterprotesters and fled the scene. Afterward, his sympathizers used Twitter accounts and message boards to share collages that misidentified the suspect, falsely alleging he was a leftist and including images of innocent people.

Many of these false claims were repeated in conservative media and permeate online circles to this day.

The report says journalists and social media users should always search for the origin of an image, and use time stamps and metadata to determine whether a collage was made by an individual or pieced together by a group. The report also calls on social media platforms to more effectively hide evidence collages containing misinformation.

Keyword Squatting

The report defines keyword squatting as a technique of creating social media accounts associated with terms meant to “capture and control search traffic.”

In keyword squatting, social media users co-opt keywords “related to breaking news events, social movements, celebrities, and wedge issues,” researchers said. Manipulative users accomplish this using fake accounts “with fabricated attribution and bad-faith commentary,” they added.

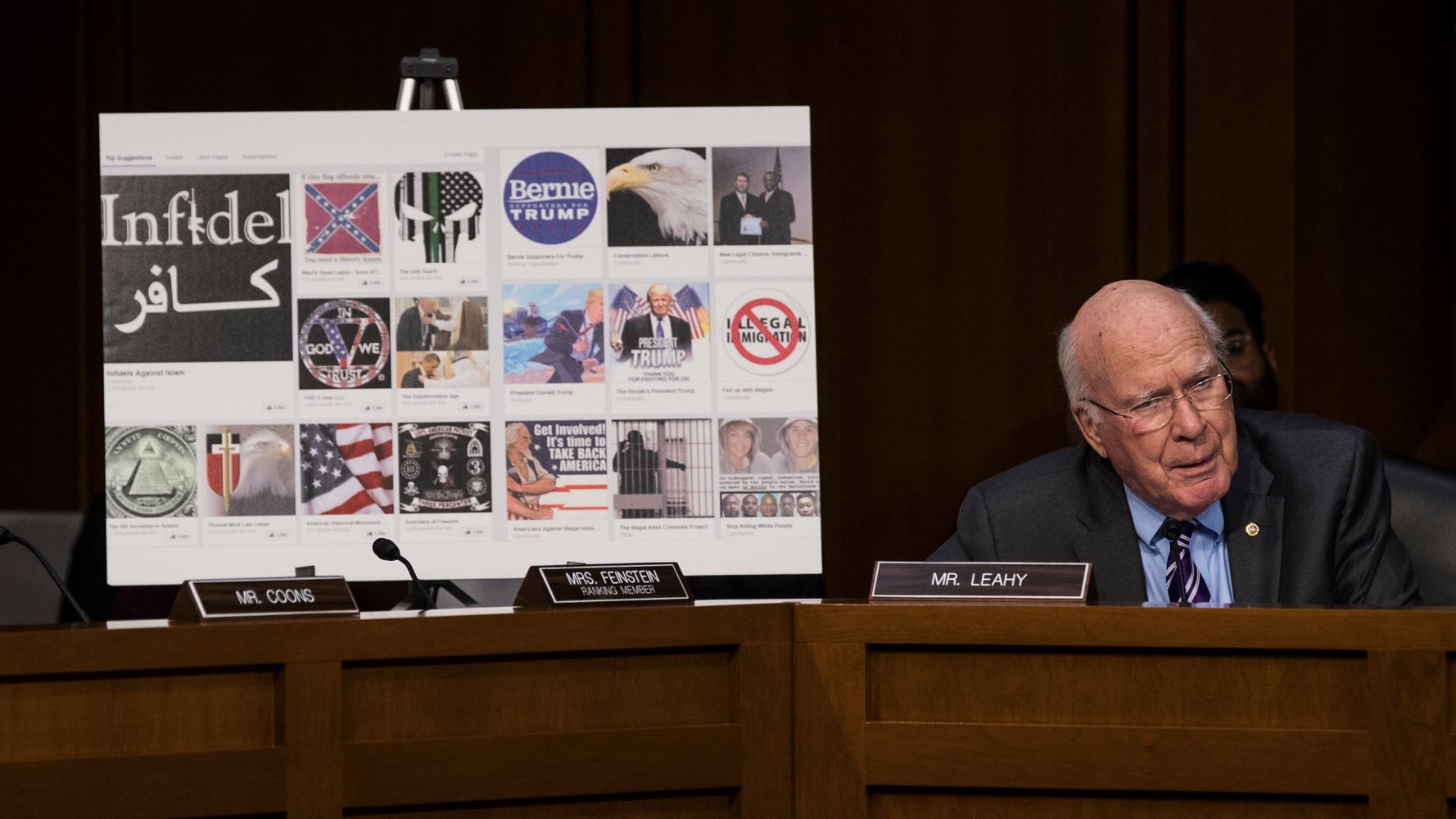

The report cites the Russian government’s effort to manipulate the 2016 U.S. election as an example of keyword squatting. In 2016, a Russian-backed firm largely targeted African Americans on social media by using fake accounts and hashtags related to social justice, according to a report commissioned by the Senate Intelligence Committee.

The accounts and ads were promoted to social justice advocates in the U.S. and frequently invoked phrases popularized by the Black Lives Matter movement to give the impression that the creators were Americans.

Researchers for Wednesday’s report said social media users should consider it a red flag when accounts they follow for news “are not associated with any identifiable person or entity.” They also recommend that social media platforms make more identifying information available in the “about” or “bio” sections of a user’s account.

“When manipulators impersonate social movements,” the report said, “they can affect cultural attitudes, politics, reporting, and even policy.”

REAL LIFE. REAL NEWS. REAL VOICES.

Help us tell more of the stories that matter from voices that too often remain unheard.

[ad_2]

Source link