[ad_1]

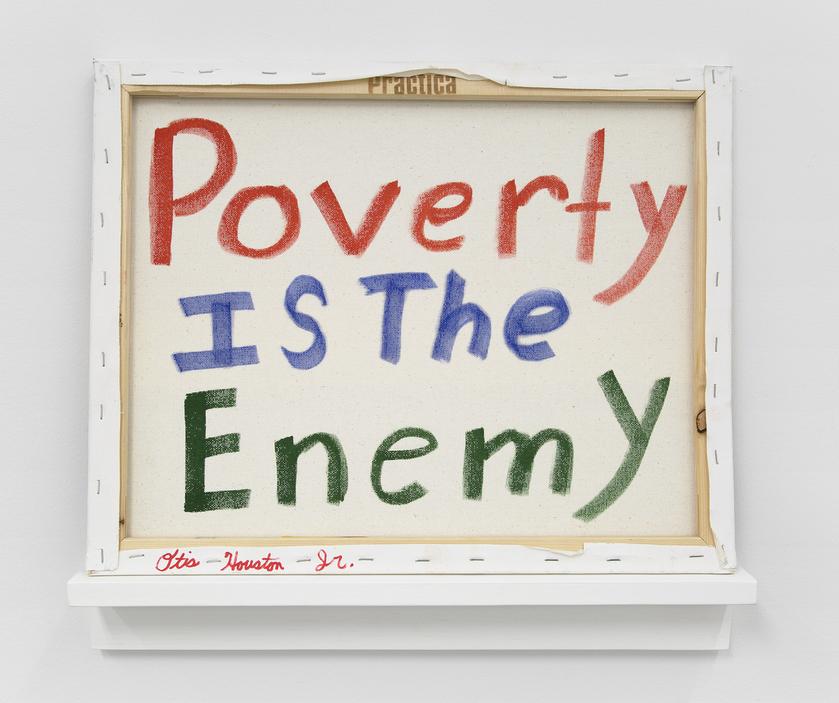

Otis Houston Jr., The Enemy (view a), 2018, marker on found painting, 15 x 20 in.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND GORDON ROBICHAUX

While presenting his work along the FDR Drive in New York’s East Harlem neighborhood over the past 21 years, the artist Otis Houston Jr. has received his share of tickets from the police. One was the result of him holding an ax during a performance. In another instance, he laid magazines on the ground, which apparently constituted littering. On a different occasion, he was informed that it is illegal to tie a rope to a tree.

“If I don’t go for the thing, I get a warrant,” Houston told me one recent weekday evening, of the need to go to court after receiving a summons. “Even though it might be bogus, I’ve got to show up.” Typically, though, he’s been able to have them dismissed without too much trouble. “One judge told me, ‘Art for art sake!’ ” he said, laughing gregariously while slapping his knee like the gavel coming down.

For that, we should be grateful. Because every time Houston steps onto the side of the highway, his venturesome art reaches thousands of people an hour, giving drivers who may be on long commutes or stuck in traffic a jolt of electricity through signs with poignant, sometimes slyly funny phrases (“I Bank/at CHASE/I’m in the Race,” one read) or unexpected sights—like, say, a man posing with a huge slice of watermelon atop his head and a paintbrush in his hand.

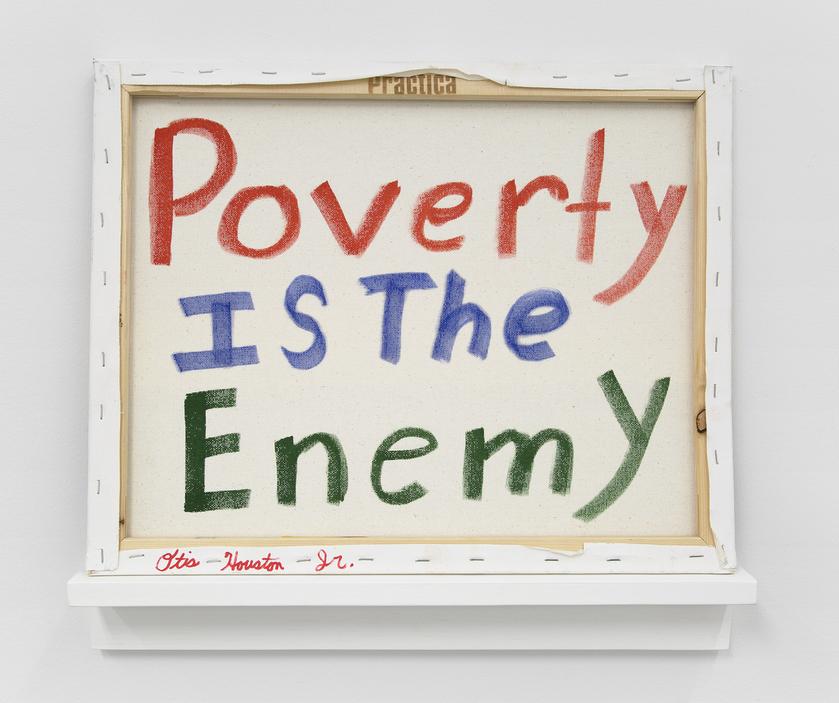

Otis Houston Jr. performing at Gordon Robichaux, New York, 2018. At left, Otis Houston Jr., Peace, 2018; at right, Florence Derive, Letter with Capucine, 2017.

COURTESY GORDON ROBICHAUX

In the process, Houston has accomplished a rare feat for an artist—he’s become a local celebrity, part of the fabric of New York. It seems that everyone who regularly cruises the FDR has a story about spotting him, even if they do not know who he is. (He only sometimes displays signs with his name or that of his nom de guerre, Black Cherokee, which he’s said he picked as a reference to his racial identity.)

The artist Miles Huston first recalls seeing Houston around 2005, while driving to and from school in Boston. “I will never forget it,” Huston said. “He was in a rocking chair, shirt off, rocking away with an apple balanced on his head. He was waving to the cars, but his mouth was covered with red duct tape. Behind him was one of his towels zip-tied to the fence. In red spray paint it said, ‘Hey Mr. Trump, wanna go fishing?’ At some point, I pulled my car over one day and introduced myself, and then he gave me his cell number.” (In 2016, the two staged a show at Cave, an artist-run exhibition space, in Detroit.)

Of that Trump piece, Houston said, with a wry smile, “I was trying to bring him down to my size.” The artist was sitting in Gordon Robichaux gallery near Union Square, where he is showing a number of playful sculptures and incisive text works alongside pieces by the French artist Florence Derive in a show that runs through December 16. He had walked over from the Midtown building where he is a maintenance worker during the day, and he was wearing a flannel shirt tucked into dark pants and black sneakers. He looked younger than his 64 years.

Not incidentally, much of his work has to do with healthy living. “A lot of women are mildly depressed—men, too—and they wouldn’t be if they exercised,” Houston said. “I say that because when I don’t exercise, that’s how I feel.” While standing along the FDR, usually underneath the looping onramps for the Triborough Bridge, “I do stuff, I do exercises, I do stretching—weights, poses.” One sign he has shown in the past read: “I’m crazy but don’t use drugs drink or smoke.”

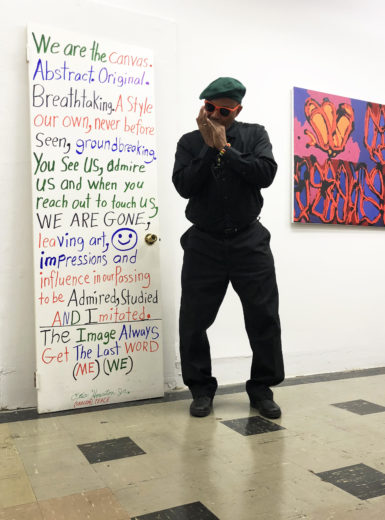

Installation view of “The image Always Get the Last WORD: Otis Houston Jr. and Florence Derive” at Gordon Robichaux in New York, through December 16, 2018.

COURTESY GORDON ROBICHAUX

Houston became interested in health, and took art classes, while imprisoned in the 1980s, when he was serving more than six years on a heroin charge. After his release, he worked as a meatpacker and held other jobs. One day he came across a book that discussed art as a tool for therapy, which led him to start showing his work along the FDR in 1997, a couple blocks from the home he shares with his wife.

The responses from passersby keep him going. “I go down for one hour, two hours, three hours,” Houston said, “and they yell at me, ‘You’re the best artist in New York! You fantastic! You awesome! You great! We love you!’ ” When approached by officers of the law, he said, he tells them, “Every time I come down here the people treat me nice. If they didn’t treat me nice, I wouldn’t keep coming down here. How they treat you?”

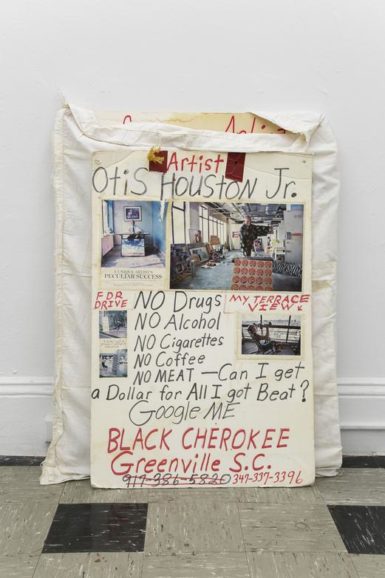

Otis Houston Jr., Advertisements, 2008–18, marker, rope, tape, and collage on found boards; laundry bag, 41 x 31 x 3.5 in.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND GORDON ROBICHAUX

Houston was born in Greenville, South Carolina, in 1954, and speaks quickly, with a Southern twang. He grew up with family members who made things and learned from them. “My granddaddy was a plasterer, my father was a plasterer, and my uncle was a plasterer,” he said. His mother worked at the Catholic school he attended, cooking and assisting the monsignor. He was born a natural performer, and recalls one teacher telling him: “Otis, you could be a leader.” His reply: “Sister, I don’t want to be no leader!”

He is also a natural raconteur, occasionally launching into verses of rhyming poetry that he’s composed about his life and practice as we talked. (At the gallery on December 16, at 6 p.m., he’ll perform after Agosto Machado reads a poem by Jack Pierson about Derive and her work.) Asked about moving up to New York, he began: “Came to Harlem, 1969 / Guy in the streets started selling cocaine capsule dimes / I was fast, but they thought I was slow / And then I started sniffing the blow.” He added later in the poem, “I’m a great artist and I want the world to know / I could have been even better if I didn’t mess with that blow.”

In 1976, he served nine months in prison on a cocaine charge, did a stint as a boxer, and got shot at the end of the decade. He switched again to a lilting delivery to set the scene, emphasizing every word: “Laying here in my hospital bed / with two bullets in my back, thanking the Lord I’m not dead / Laying here with a tube in my chest / And thanking the Lord because he knows best / Laying here thinking of all the miles I’ve run / And thanking the Lord that I still can see the sun.”

Such potent and clear-eyed sentiments pervade much of his work at Gordon Robichaux gallery, as in a black canvas propped atop a chair that declares in white letters, “A HAPPY DEATH IS A MASTERPIECE AND NO MASTERPIECE WAS PERFECTED IN A DAY.” And his sculptures have a jaunty, uncanny pathos, like The Thangofmajig (2018), a chair with its four legs perched atop two sets of polished shoes and clothespins of various colors ornamenting a plastic ring that he’s affixed to the seatback with a large paperclip. He finds most of his materials in the building where he works or elsewhere in the city. “I see junk and stuff laying around,” he said, “and I think, What can I do with that?”

Otis Houston Jr., The Thangofmajig, 2018, mixed media (found and altered objects), 26.75 x 14.5 x 38 in.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND GORDON ROBICHAUX

Signs he made for the show address charged issues of the present moment—of race, class, and art itself—with brutal bluntness. A few sentences, spelled out with markers in various colors, include “Poverty Is The Enemy,” “BLACK TRASH” (in a new work titled What You See Is What You Get), and “We are the canvas. Abstract. Original. Breathtaking.”

In his work, Houston is “saying these things that maybe everybody is thinking,” the artist Sarah Braman said. She described the messages as “confounding and moving, and maybe upsetting or delightful.” Braman first saw it while driving with her husband, Phil Grauer, and their children back and forth between Massachusetts, where they live, and Lower Manhattan, where they co-run the Canada gallery. “We built up a relationship honking and waving and talking to him out the window,” she said. “I thought it was always such inspiring and really good sculpture.” Eventually they pulled off the highway and met. In 2009, they included some of Houston’s sculptures in a show at Canada.

“If I have one regret of my experience in New York involved in the arts,” Braman added, “the only real regret I have is that we didn’t find a way to get some photo documentation of all that amazing work.”

Indeed, Houston’s practice has mostly been fly-by-night. While he’s also shown at the Room East gallery and the Socrates Sculpture Park in New York, his art generally appears only for as long as he has the time to show it. Like the public performances of Stephen Varble or Gordon Matta-Clark’s acquisition of slivers of land in New York, his work invites viewers to see the city anew, as a place where any space, at any moment, can become a site for art that bewilders and entertains and prods—and that sticks with people. It’s art about standing one’s ground.

At one point, I asked Houston what he does what when he’s not working or making art. “Read, exercise, and go around and look at things,” he replied. “I always say, ‘I’m not from New York. Everywhere I go, I’m sightseeing.’ ”

[ad_2]

Source link