[ad_1]

How a scholarship helped — and didn’t help — descendants of victims of the 1923 Rosewood racial massacre.

By Jordannah Elizabeth, New York Amsterdam News

Many states in America are moving into “Phase 2” of reopening. With the utmost respect to those who have lost family members and have been furloughed and laid off, I personally wish we would move a little slower. It’s important that people get back to work, but at what cost? Black people have the highest COVID-19 death rate in the nation. It is possible a quick reopening will send the Black community into a deeper health crisis. It is up to us to be self-sustaining when it comes to social distancing and wearing protective masks. We have the power to take our collective lives in our own hands while complying with the World Health Organization. Nas asked the question in his prolific album, “Illmatic,” “Whose world is this?” He confidently answered, “It’s mine, it’s mine, it’s mine.” Don’t forget that this world is ours just as much as anyone else’s.

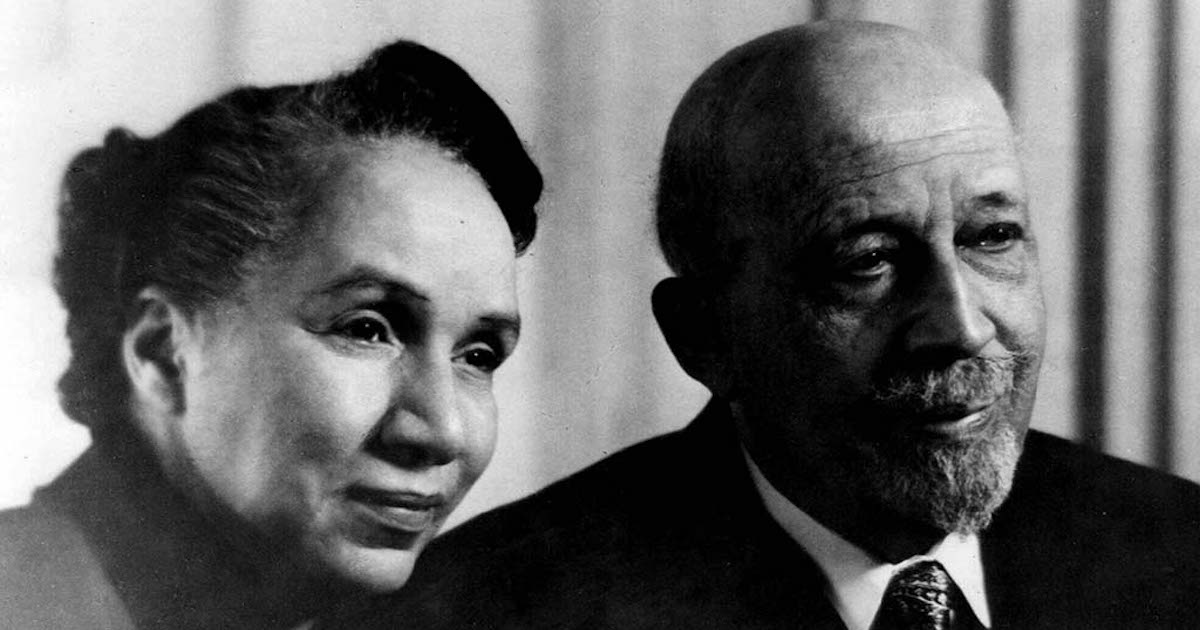

While social distancing and working from home, I found myself going through archives of articles and interviews searching for specific topics in jazz and classical music, as I considered continuing the conversation of Black classical composers and historical Black music. I found that my 2015 article, “10 Black female composers to discover,” is still the only list to highlight Shirley Graham Du Bois, the wife of W.E.B Du Bois, who “was the first Black American woman to compose an opera for a major professional organization.” Black women like Florence Price, Julia Perry and Undine Smith Moore have been cited in other articles, but Du Bois still goes largely unnoticed.

Featured Image, Lotte Jacobi, Courtesy University of Massachusetts Amherst

Full article @ New York Amsterdam News

CONTEXT: W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American sociologist, socialist, historian, civil rights activist, Pan-Africanist, author, writer and editor. Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in a relatively tolerant and integrated community, and after completing graduate work at the University of Berlin and Harvard, where he was the first African American to earn a doctorate, he became a professor of history, sociology and economics at Atlanta University. Due to his contributions in the African-American community he was seen as a member of a Black elite that supported some aspects of eugenics for blacks. Du Bois was one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909.

Before that, Du Bois had risen to national prominence as the leader of the Niagara Movement, a group of African-American activists that wanted equal rights for blacks. Du Bois and his supporters opposed the Atlanta compromise, an agreement crafted by Booker T. Washington which provided that Southern blacks would work and submit to white political rule, while Southern whites guaranteed that blacks would receive basic educational and economic opportunities. Instead, Du Bois insisted on full civil rights and increased political representation, which he believed would be brought about by the African-American intellectual elite. He referred to this group as the Talented Tenth, a concept under the umbrella of Racial uplift, and believed that African Americans needed the chances for advanced education to develop its leadership.

Racism was the main target of Du Bois’s polemics, and he strongly protested against lynching, Jim Crow laws, and discrimination in education and employment. His cause included people of color everywhere, particularly Africans and Asians in colonies. He was a proponent of Pan-Africanism and helped organize several Pan-African Congresses to fight for the independence of African colonies from European powers. Du Bois made several trips to Europe, Africa and Asia. After World War I, he surveyed the experiences of American black soldiers in France and documented widespread prejudice and racism in the United States military.

Du Bois was a prolific author. His collection of essays, The Souls of Black Folk, is a seminal work in African-American literature; and his 1935 magnum opus, Black Reconstruction in America, challenged the prevailing orthodoxy that blacks were responsible for the failures of the Reconstruction Era. Borrowing a phrase from Frederick Douglass, he popularized the use of the term color line to represent the injustice of the separate but equal doctrine prevalent in American social and political life. He opens The Souls of Black Folk with the central thesis of much of his life’s work: “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line.”

His 1940 autobiography Dusk of Dawn is regarded in part as one of the first scientific treatises in the field of American sociology, and he published two other life stories, all three containing essays on sociology, politics and history. In his role as editor of the NAACP’s journal The Crisis, he published many influential pieces. Du Bois believed that capitalism was a primary cause of racism, and he was generally sympathetic to socialist causes throughout his life. He was an ardent peace activist and advocated nuclear disarmament. The United States’ Civil Rights Act, embodying many of the reforms for which Du Bois had campaigned his entire life, was enacted a year after his death.

W. E. B. Du Bois. (2020). Retrieved July 05, 2020, from Wikipedia.

[ad_2]

Source link