[ad_1]

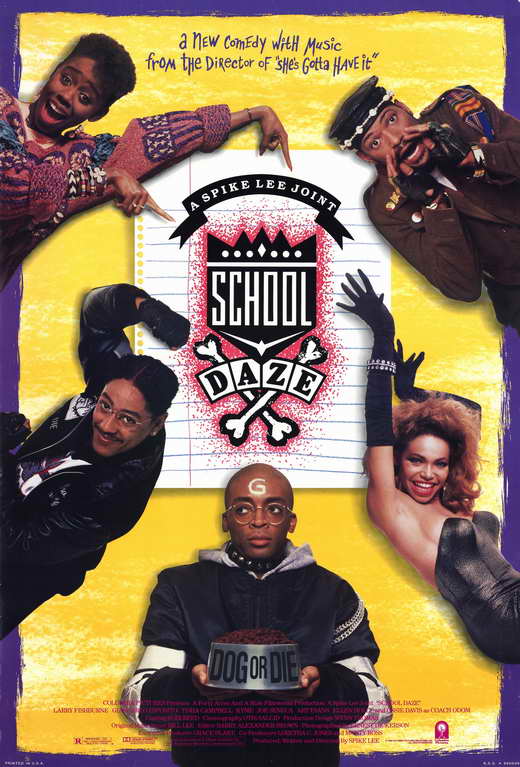

On the night of February 11, 2018, the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) hosted two sold out screenings for the thirtieth anniversary of Spike Lee’s School Daze. Lee was in attendance at both School Daze screenings that night (as he was two weeks later for another screening at the Fox Theater in Atlanta). Although he was only slated to give the introduction to our 10:00 pm screening, he sat through the entire show watching and cheering along. There’s nothing quite like seeing School Daze with a lively Black audience in Brooklyn full of HBCU alumni and Greeks rocking their various colors, who know all the words and dance moves to “Be Alone Tonight.”

Coincidentally, the thirtieth anniversary of School Daze happened to fall near the February release of Stanley Nelson’s HBCU documentary Tell Them We Are Rising. Though Tell Them We Are Rising covers other territory on HBCU history, it doesn’t address the way that HBCUs have been represented in popular culture. Spike Lee’s School Daze is a milestone in this regard as the first feature film set in an HBCU. In the Twitter chat that coincided with the PBS premier of Tell Them We Are Rising, I noticed many people citing School Daze (along with A Different World) as their first introduction to HBCUs.

Literary representations of Black college life go back as far as Sutton Griggs’s 1899 novel Imperium in Imperio. Other novels that are set at HBCUs include Nella Larsen’s Quicksand (1928), J. Saunders Redding’s Stranger and Alone (1950), Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (1952), and Chester Himes’s The Third Generation (1954). Maybe the closest literary cousins to School Daze are two novels of 1970s student protest, Gil Scott-Heron’s 1972 The Nigger Factory (based on Lincoln University) and Alice Walker’s 1974 Meridian (based on Spelman College). Both novels by Walker and Scott-Heron feature student activists at Black colleges who are at odds with their conservative administrations.

While the aforementioned novels have literary and historical value, the medium of film has the potential for greater impact in terms of audience and influence. Getting a script about Black higher education distributed in theaters was a remarkable achievement in 1988. And if these thirtieth anniversary screenings are any indication, School Daze has stood the test of time. It has found new and younger fans, and it still has the power to provoke conversations about HBCUs and their social, political, and intellectual value.

The first voices heard in School Daze are those of the Morehouse College Glee Club singing, “I’m Building Me a Home.” The song accompanies the film’s opening montage, a photo essay of African American history that moves from the Middle Passage through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, situating the history of Black higher education within a larger Black freedom struggle. “Mission College” is a stand-in for all HBCUs. While the “home” being built in the song is a spiritual one, these material earthly houses of Black higher education are important spaces for Black intellectual development and political organization. The montage shows this connection by featuring images of leaders such as Mary McLeod Bethune, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Kwame Ture (Stokely Carmichael) who have ties to HBCUs.

While the film is a celebration of HBCU life, School Daze draws its energy from conflict. Conflict between students and administrators, between men and women, between light-skinned and dark-skinned Black people, between different Greek organizations, and between the Black elite and the Black masses. This conflict is really what gives the film its authenticity. School Daze pulls back the curtain to outsiders who may have never seen an HBCU homecoming or a step show before, but Lee refused to sacrifice the complexity and internal conflict within Black college life. His fictional portrayals led to real-life clashes with Atlanta University Center administrators. Morehouse president Hugh Gloster eventually banned Lee from shooting the rest of the film on the campus, forcing Lee to finish shooting the remaining scenes across the street at Atlanta University (which soon merged with Clark College to form CAU in 1988).

Laurence Fishburne plays the main character Dap, the resident radical who wants Mission College to divest from South Africa in protest of apartheid. This storyline calls attention to the complicated politics of HBCUs where administrators are schooled in uplift and respectability, and discourage student activism as a distraction from the work of uplifting the race. These administrators are also concerned about financial support from white philanthropists who “don’t like being told what to do with their money,” as one of the Mission College officials says in the film. School Daze dared to confront the dirty laundry topics of colorism, sexism, and classism, most famously in the musical number “Straight and Nappy,” a song about “wannabees” and “jigaboos” that addresses the prevalence of colorism among Black women and contributes to a long history of colorism critiques in Black literature and cinema.

One of the loudest cheers at our screening was for an early-career Samuel Jackson who appears late in the film in a scene at the local chicken spot where the Mission College guys get into a confrontation with a group of ATLiens. This is a crucial scene of town-and-gown conflict that introduces an important class critique into the film. Dap is the woke campus radical who positions himself against the bougie Negroes of Mission College. But when they step off campus and encounter the lumpenproletariat, he’s exposed as just another privileged college kid. The dynamic that Spike Lee captures in that scene is prevalent in Atlanta with its concentration of Black colleges in the Atlanta University Center. There’s an abiding resentment toward the students who cycle in and out every year from the people for whom the city is a home and not just a four-year playground.

Perhaps the most important thread running throughout Lee’s entire career is the idea that film has never been a neutral medium for representations. In his book Facing Blackness: Media and Minstrelsy in Spike Lee’s Bamboozled (2015), film critic and BAM curator Ashley Clark argues for the centrality of Bamboozled in Lee’s filmography precisely because it emphasizes the ways that Hollywood is historically bound up with white supremacy. One of the first commercially successful feature films and arguably the most important in American cinema is the pro-Confederate, white supremacist propaganda film The Birth of a Nation (1915). The first talkie was a Blackface minstrel show, The Jazz Singer (1927). For most of its history, Hollywood has perpetuated images of whiteness and ugly stereotypes of non-white people. Because of that history there is a burden of representation that haunts the Black filmmaker, who is often under pressure to positively represent the race. “Representation matters” is the watchword these days with the runaway success of recent blockbuster films Black Panther and A Wrinkle in Time. But that same paradigm also means Black filmmakers sometimes face criticism when they dare to explore the unflattering complexities of Black life.

School Daze was a political and aesthetic intervention that brought HBCU life and Black culture to the big screen. Several of its cast members went on to appear in the successful TV show A Different World (1987-1993), including Jasmine Guy, Darryl Bell, and Kadeem Hardison. It also paved the way for later HBCU films and shows like Drumline (2002), Stomp the Yard (2007), and The Quad (2017). With School Daze, Spike Lee achieved the vision that Lincoln University alumnus Langston Hughes expressed in his 1926 essay “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” when young Black artists in his own time were being challenged about their representations of Blackness: “We build our temples for tomorrow, strong as we know how, and we stand on top of the mountain, free within ourselves.”

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

[ad_2]

Source link