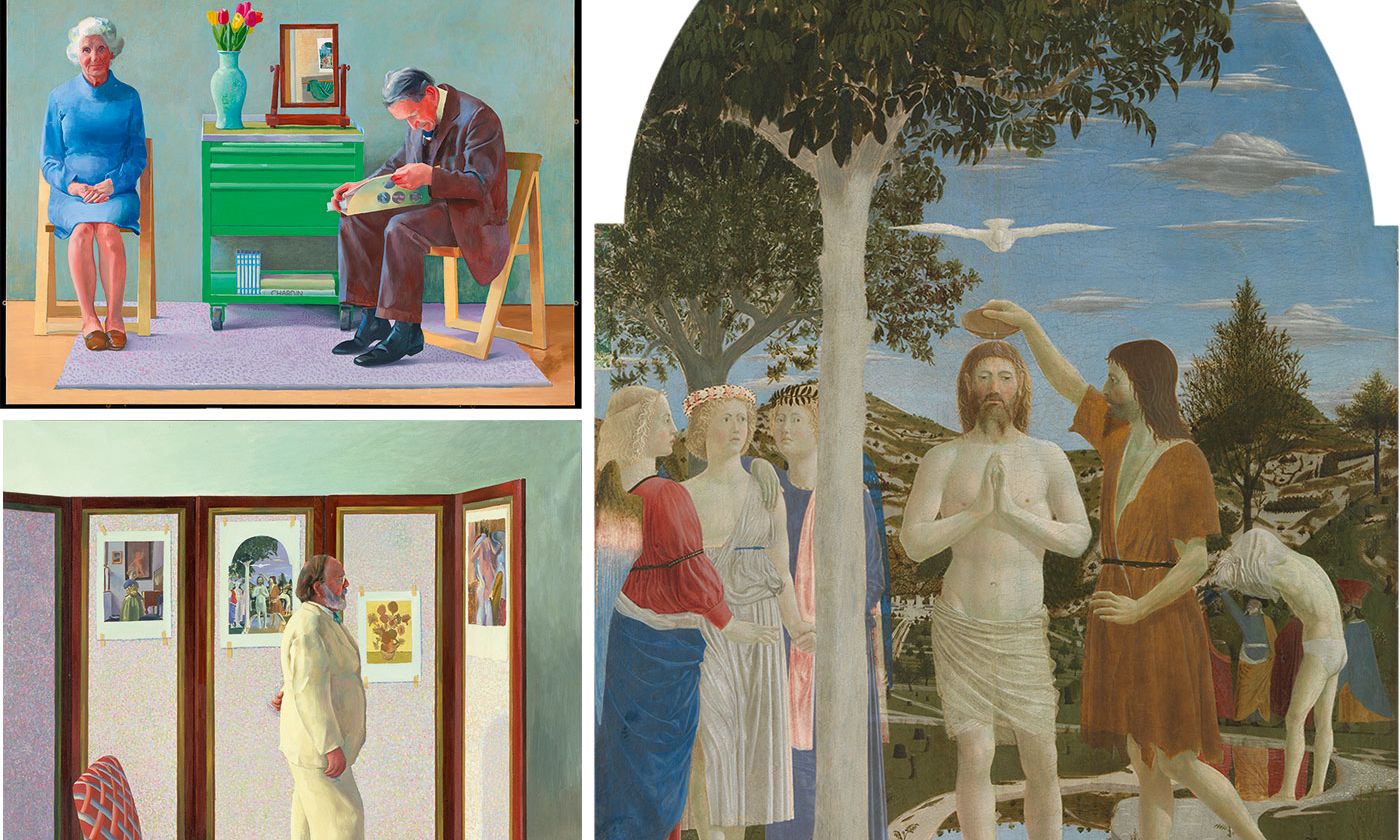

Clockwise from right: Piero della Francesca, The Baptism of Christ (around 1437-45) and two 1977 paintings by David Hockney which feature the Piero: Looking at Pictures on a Screen and My Parents. All three paintings feature in the free exhibition Hockney and Piero: A Longer Look, which runs at the National Gallery until 27 October. Piero: © The National Gallery, London. My Parents: © David Hockney. Photo: Tate, London. Pictures on a Screen: © David Hockney

The pulling power of a show featuring just two paintings by the Baroque bad boy Caravaggio at the National Gallery in London surprised seasoned culture commentators. The exhibition The Last Caravaggio (until 21 July) featured The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula (1610), loaned by the Gallerie d’Italia in Naples, alongside a work from the National Gallery collection, Salome receives the Head of John the Baptist (1609-10). “[I] couldn’t believe my eyes as queues snaked out of Room One of the Trafalgar Square site and down the stairs,” writes Nick Clark, acting culture editor at the Evening Standard.

The popularity of the two-hander, an integral part of the museum’s bicentenary celebrations (NG200), has taken aback even Jane Knowles, the National Gallery’s director of public engagement. “Caravaggio has that irresistible combination of striking artworks and a fascinating life story, so we were expecting it to be popular. But it has been extraordinary to see the queues of people waiting to see the exhibition,” she says. Audience surveys undertaken during the run will eventually provide an analysis of the demographics, but “you can really tell it is an incredibly diverse audience that this show appeals to”, she adds.

Jane Knowles: the National Gallery's director of public engagement

Photo © National Gallery, London

The formula appears to be a winning one—present an easily recognisable artist and show paintings that tell a fascinating story, ultimately creating that “must-see” buzz (it also helps that the artist, undergoing something of a renaissance, takes centre stage in the hit Netflix show Ripley). But a more obvious factor also comes into play—the Caravaggio display was free, enabling visitors to experience masterpieces without shelling out during a cost-of-living crisis. This model is an integral strand of the NG200 project, with other small-scale, big-name shows in the pipeline including a fascinating dialogue between David Hockney and the 15th-century master Piero della Francesca, artist of one of the National Gallery’s greatest masterpieces, The Baptism of Christ (around 1437-45), which runs until 24 October.

Marketing these shows would appear to be a challenge because the focus is on a limited number of works. But, as Knowles points out, “The notion of the single-painting show is in the gallery’s DNA—we practically invented this concept during the Second World War with the Picture of the Month series! We know that these exhibitions remain hugely popular. Motivations will differ from person to person but in essence we hope that they offer visitors the chance to delve into a single great painting in depth and have a completely different type of experience compared to visiting larger exhibitions featuring multiple works.”

Museum commentators watch with interest how the National Gallery is in effect rebranding works drawn from the permanent collection, presenting them in fresh ways. Knowles says that pairing works with loans from other venues enables the museum to make connections across the centuries. “This is where we can draw the journeys our visitors can go on, encouraging a greater exploration of the permanent collection to see how these great paintings of the past can inspire new ideas for the future, and how it all starts with just one painting in a room that we have invited people in to see for free.”

So did the museum decide a quota of free shows should be a part of NG200? “Very much so,” Knowles says. “This follows on from our strong commitment over the past 200 years to offering as many opportunities as possible for people to access great art, with the fewest barriers— a key one of those being financial.” Indeed, this idea of accessibility is a cornerstone consideration.

When the National Gallery was founded in 1824, the objective was to establish a museum of the very best paintings for the enjoyment of the British public that, in the words of the founding document, should be free to anyone who applied at the door, she adds. “Those principles of excellence and access are still very much our guiding ethos today, but of course, nearly 200 years later, we do things a little differently to the Georgians! Key to this is that we no longer expect everyone to come to us.”

NG200 has been rolled out as a countrywide initiative, with free activities at its core. “A key aim of NG200 is to collaborate with local partners and communities both in London and across the UK to ensure that everyone is able to engage with their national collection—[for] both existing and new audiences,” Knowles says.

This is reflected in ideas and projects such as National Treasures, whereby 12 of the institution’s greatest pictures are loaned to museums around the UK. Diego Velázquez’s The Toilet of Venus (“The Rokeby Venus”, around 1647-51)—one of the National Gallery’s headline-making paintings that has been at the centre of women’s voting rights and climate protests over the past 120 years—is, for instance, the focus of National Treasures: Vélazquez in Liverpool at the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool (until 26 August). J.M.W. Turner’s The Fighting Temeraire (1839) is at the Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne, at the heart of an exhibition about 19th-century industrialisation (until 7 September), while Caravaggio’s The Supper at Emmaus (1601) is on loan to the Ulster Museum, in Belfast (until 1 September), where it is reunited with its companion canvas The Taking of Christ (1602), on loan from the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin.

National Treasures is a crowdpleaser but the key to the NG200 campaign will be to build up audiences of all ages (the hallowed “multi-generational” phenomenon). The NG200 programme with all its strands is designed to reach everyone, everywhere, and celebrate 200 years of bringing people and paintings together, Knowles says. With so many activities lined up, some may slip slightly under the radar.

How will the Art Road Trip initiative make an impact, for example? Over the next year, this travelling art studio programme will host around 200 public events, delivering creative workshops to diverse groups in out-of-the-way locations (in June, the Art Road Trip partnered with Community Arts Partnership in Northern Ireland to deliver activities at sites such as residential homes).

“Art Road Trip we are especially proud of as the project places special emphasis on people who have the least access to the arts and creative opportunities, and seeks to champion the creativity of individuals who might otherwise feel excluded from cultural infrastructure and introduce them to their national collection,” says Knowles, who adds that the studio will work with more than 40,000 people across the country, bringing art and ideas inspired by the National Gallery’s collection to the heart of their communities. This has a Trojan horse effect, opening up opportunities for local schools to take part in other National Gallery initiatives such as Take One Picture and Articulation, and the Keeper of Paintings digital scheme.

Digital platforms matter just as much as bricks and mortar in “democratising” the collection. The NG200 network of 200 social media creators from across the UK—some from under-represented communities aimed at boosting diversity—is part of this drive. The clearest indication that the museum wants to increase accessibility however would be to retain free entry (this could again become a political hot topic following the UK general election this month).

Is free admission still an important strand? “Visiting the National Gallery for free stretches back almost 200 years,” Knowles says. “It is something generations of the British public have enjoyed and benefited from and signals the importance that we attribute to our national museums. We strongly feel that it is a key part of our national life, and we are keen to maintain it.”

David Hockney's My Parents (1977)

© David Hockney. Photo: Tate, London

David Hockney's Looking at Pictures on a Screen (1977)

© David Hockney

The artist David Hockney has had a lifetime’s attachment to the National Gallery and has been inspired by its collection for more than six decades. Hockney and Piero: A Longer Look places one of the gallery’s abiding favourites, Piero della Francesca’s The Baptism of Christ (around 1437-45), in the context of two 1977 paintings by Hockney that feature the Piero: My Parents, a portrait of Kenneth and Laura Hockney voted the UK’s favourite work of art in a 2014 poll for a scheme called Art Everywhere, backed by the Art Fund; and Looking at Pictures on a Screen, a portrait of Hockney’s friend the late Henry Geldzahler, curator of 20th-century art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, in which three other National Gallery showstoppers are shown—Johannes Vermeer’s A Young Woman standing at a Virginal (1670-72), Van Gogh’s Sunflowers (1888) and Edgar Degas’s After the Bath, Woman drying herself (1890-95). Susanna Avery-Quash, the show’s lead curator, says it is designed to draw attention to “the powerful if hidden story of the National Gallery as a catalyst in the creative life of the nation through its encouragement of contemporary artists to draw inspiration from its collection”.

Piero della Francesca, The Baptism of Christ (around 1437-45)

© the National Gallery, London

In a show that attracted large crowds between 18 April and 21 July this year, the final known painting by Caravaggio, The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula (1610), was loaned by the Gallerie d’Italia in Naples, and shown in company with another of the artist’s late works, Salome receives the Head of John the Baptist (1609-10) from the National Gallery’s collection. The Martyrdom was reattributed to Caravaggio in the 1980s after the discovery of a letter of May 1610 (also in the exhibition), in the Doria d’Angri family papers in the State Archives in Naples. The letter reveals, as Gallerie d’Italia director Michele Coppola says, that “the painting is by Caravaggio [and traces] it back to a commission by the Genoese Marco Antonio Doria [Marcantonio Doria], fixing its date and identifying its subject which until then had been … obscure”. The work was painted shortly before the artist left Naples for Rome in 1610, seeking a pardon for killing a man in a swordfight four years earlier. Caravaggio died on the way to Rome. The painting, featuring a shadowy self-portrait, is an emblem of the final stages of Caravaggio’s drama-filled life.

The National Gallery’s Salome receiving the Head of John the Baptist (1609-10) by Caravaggio

© the National Gallery, London

Caravaggio’s The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula (1610) has been lent by the Gallerie d’Italia in Naples for the Last Caravaggio exhibition

© Archivio Patrimonio Artistico Intesa Sanpaolo; Photo: Luciano Pedicini

Edgar Degas’s Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando (1879)—a portrait of the celebrated circus artist Anna Albertine Olga Brown (1858-1945), known on stage as Miss La La, and first shown at the Fourth Impressionist Exhibition (though delivered two weeks late)—is the focus of this “Discover” exhibition in which the National Gallery aims to shed light on lesser-known masterpieces in the collection. In the painting, Olga/Miss La La—the daughter of a white Prussian mother and African-American father, known for inventing a new school of “iron jaw” feats of strength—is seen from below, suspended from a rope held between her teeth by a leather mouthpiece, as she is raised to the domed ceiling of the Cirque Fernando, near the Montmartre district of Paris. Degas attended the enormously popular show (making quick sketches in his notebook) in the winter of 1878-79 and asked La La to pose in his studio on four or five occasions, suspended by her mouth for two and a half hours at a time using a reconstruction of the ropes and pulleys from her act (represented in the show by a pastel sketch on loan from the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles). Anne Robbins, curator of paintings at the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, and lead curator of this loan show, tells the story of Olga using previously unseen family photographs, theatre posters from France’s Bibliothèque Nationale and rarely seen sketches by Degas.

Edgar Degas’s Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando (1879). The painting was acquired in 1925 through the Courtauld Fund for buying Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works

© the National Gallery, London

On 10 and 11 May, a history of the National Gallery was projection-mapped on to the museum’s façade

© the National Gallery, London

The bicentenary of the founding of the National Gallery on 10 May 1824.

Big Birthday Weekend celebrations featured the projection of an eight-minute history of the gallery on the Trafalgar Square façade.

The National Treasures exhibitions—with 12 of the gallery’s greatest masterpieces lent to museums in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland (each accompanied on its travels by one of the gallery’s trustees)—opened around the UK.

The Art Road Trip reached its first stop (of 18) as the gallery’s mobile art studio arrived in Derry, the start of 12 months in which it is due to host 200 events involving 24 local organisations.

The exhibition Discover Degas & Miss La La opened.

The final chance to see The Last Caravaggio, and preparations begin for the redisplay of the collection.

The National Gallery’s Free Festival of Art lands in Trafalgar Square, made by children, for children. Meanwhile, Summer on the Square is a month-long programme of free, daily creative sessions and activities to inspire children and families to create their own masterpieces.

Hockney and Piero: A Longer Look opens.

Sunflowers (1888) features in the Van Gogh show opening on 14 September

© the National Gallery, London

The loan exhibition Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers opens. It marks the centenary of the gallery’s acquisition of the artist’s paintings Sunflowers and

Van Gogh’s Chair (both 1888).

The launch of NG Stories.

Duccio’s Madonna and Child (around 1290-1300) features in Siena: The Rise of Painting

creativecommons.org

Siena: The Rise of Painting 1300-1350 opens at the National Gallery.

The Sainsbury Wing reopens as the main entrance and starting point for the chronological rehang of the collection. New supporters’ house and creative learning centre due to open during 2025.

The artist Jeremy Deller presents the concluding“bacchanal” of his The Triumph of Art—a year-long collaboration with the Box in Plymouth, Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art & Design in Dundee, Mostyn in Llandudno and the Playhouse in Derry.