[ad_1]

By Grace Aldridge Foster

“The Jolly Washerwoman,” by Lilly Martin Spencer, oil on canvas, 1851. (Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College)

Lilly Martin Spencer’s “The Jolly Washerwoman” (1851) looks directly at you, elbow-deep in sudsy water, grinning widely. Hanging on the wall to her left is John Rose’s “Miss Breme Jones” (1787), immortalized in watercolor. One foot is half-lifted as if she is walking somewhere. She is a woman in motion, painted in profile. She does not smile.

The contrast between a jovial white washerwoman and a grave African American enslaved woman is one of many in the new exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery “The Sweat of Their Face: Portraying American Workers.”

“Miss Breme Jones,” by John Rose, watercolor and ink on paper, 1785–87 (Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, Williamsburg, Va.)

Like their subjects, the artists of these two portraits are quite different: One, a 19th-century woman who was so successful her husband quit his job as a tailor to manage her artistic career. The other, a plantation owner who painted Miss Breme as a tribute to the woman who raised his children after his wife died. Yet in their time, both artists challenged the norms of classical portraiture through their choice of subject.

The challenge to academic portraiture conventions is one unifying theme of the exhibition, which features approximately 75 images of American laborers from the 18th century to the present. The show, five years in creation, kicks off the National Portrait Gallery’s 50th-anniversary celebration.

“African American Woman with two white Children,” Unidentified artist, quarter plate ambrotype, 1860 (Promised gift of Paul Sack to the Sack Photographic Trust for the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art)

“We are very interested right now at the National Portrait Gallery in making absence visible,” Curator Dorothy Moss explains. “Our early collections of 18th- and 19th-century portraiture represent elite subjects who could afford to commission a portrait. The story told through the early collections is not a full history.”

Nor is “The Sweat of Their Face” a full history of American labor. Instead, it is a broad look at the history of the portrayal of American laborers. It includes images of household maids, butlers, child laborers, construction workers, newsboys, cooks, seamstresses, custodians, gardeners, migrant workers, and more. Some of the subjects are named; many are not.

“Tommy holding his bootblack kit,” by Jacob Riis, gelatin silver print, ca. 1890 (Museum of the City of New York)

“The idea for the show came from my dissertation research about access to art museums in America in the 19th century and who museums are really for,” Moss explains. “That question of whether our visitors are coming in and finding a connection to their story on our walls is crucial to us. We want to represent as wide a story of American history as possible.”

This show is part of that project, she says. Though the exhibition works to address what has been missing in the museum’s collections, it has absences of its own. Most notably, enslaved laborers are underrepresented in the show, largely because they were almost never the subject of portraits.

“Miss Breme Jones” is a rare exception, in more ways than one.

“Workers on the Empire State Building,” by Lewis Hine, gelatin silver print, ca. 1930. (Museum of Modern Art; Committee on Photography Fund)

John Rose, the white plantation owner who painted—and owned—Breme Jones, inscribed words from John Milton’s “Paradise Lost” on the portrait. The verses he chose describe Adam’s adoration of Eve.

“It’s a tender portrayal,” Moss says. “But then again, he never did free her,” she adds.

Moss and co-curator David C. Ward, senior historian emeritus at the National Portrait Gallery, chose objects for this collection that tell the story of the legacy of slavery.

“Willie Gee” (1904), a young African American boy memorialized in oil paint by Robert Henri, was the child of enslaved parents. Ella Watson, the subject of Gordon Park’s “Washington, D.C., Government Charwoman (American Gothic)” (1942), was likewise descended from enslaved people.

“Lathe Operator Machining Parts for Transport Planes at the Consolidated Aircraft Corporation Plant, Fort Worth, Texas,” by Howard R. Hollem, digital inkjet print from color transparency, 1942. (Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress)

Such context adds richness and dimension to the images in the show. Consider Dorothea Lange’s iconic photograph “Migrant Mother” (1936) which hangs in the exhibition near J. Howard Miller’s famous “We Can Do It!” poster of Rosie the Riveter. Florence Owens Thompson, the mother in Lange’s photo, never profited from the widespread use of her image. She died in poverty.

The tragic irony of this story, and others like it, injects melancholy into a show that is at times jubilant and proud. There is no doubt that the history of American labor is rife with injustice and struggle, and a number of the portrayals in this show bring that hurt to bear.

“Young Jewess Arriving at Ellis Island,” by Lewis Hine, gelatin silver print, 1905 (Courtesy Alan Klotz Gallery; Photocollect Inc., New York City)

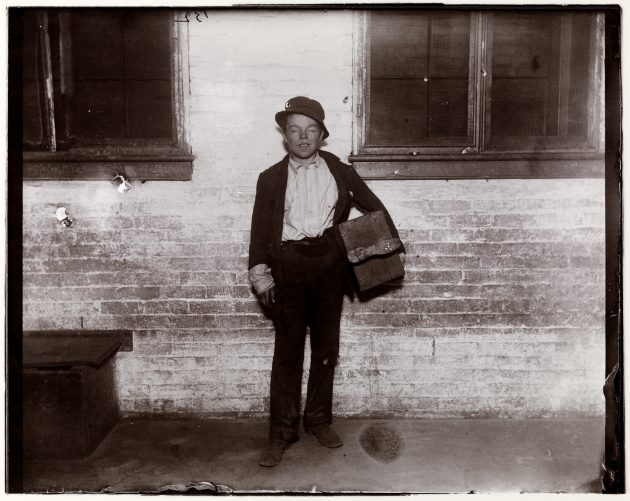

Lewis Hine’s photographs of child laborers are particularly poignant. Hine made these images as documentary evidence of poor working conditions for children. In the context of this show, they are reframed as intimate portrayals of young school-age children performing manual labor. The young girls in the portraits blend into the sepia-toned machinery around them—their individuality is at risk of slipping away, bleeding into the factoryscape.

Moss likens this precariousness to the “constant risk of disintegration” facing the worker. The desire to retain a sense of self in the midst of difficult circumstances is, to Moss, one of the most striking themes in the exhibition.

“Nine to Five,” by Josh Kline, 3-D printed sculptures in plaster, ink-jet ink, and cyanoacrylate; janitor cart, LED lights, 2015 (Courtesy of the artist / Photo by Grace Aldridge Foster)

Some pieces in the show offer bleak commentary on the status of workers, such as Josh Kline’s “Nine to Five” (2015), a 3-D printed sculpture of a custodian’s body parts mingling with his cleaning supplies on a cart.

But others convey dignity and defiance, often through a strong, direct gaze. Artist Shauna Frischkorn uses classical Renaissance portraiture techniques to portray Kean, a Subway sandwich artist resplendent in his corporate polo shirt and visor, with seriousness and self-possession.

“Kean, Subway Sandwich Artist,” by Shauna Frischkorn, digital C-print, 2014 (Courtesy of the artist)

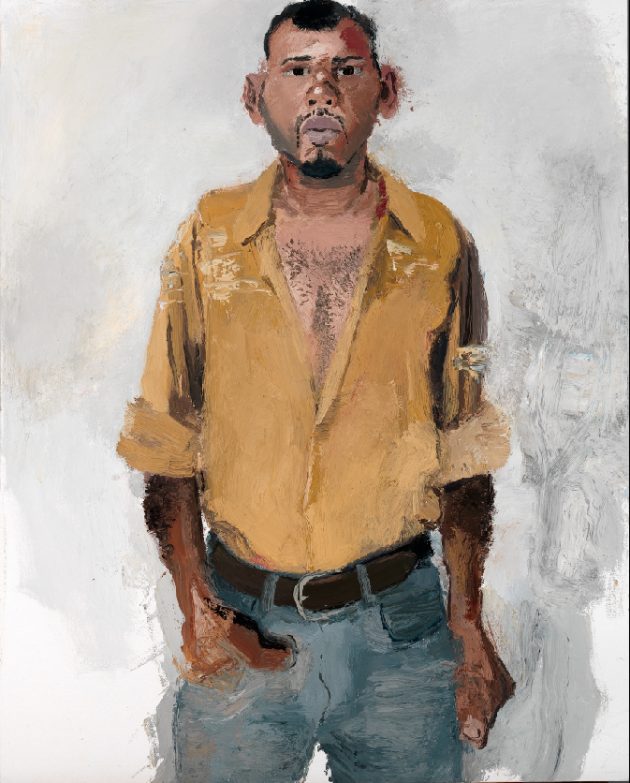

John Sonsini’s 2011 portrait of a Latino migrant worker, “Roger,” has a similar effect. The subject stands with his hands in his pockets, gazing at the viewer. He appears relaxed, yet resolute. In an image where his parts seem to slip in and out of focus—almost like he could be any one of the group of people he represents—Roger’s eyes anchor his personhood just as they grab the viewer’s gaze. Sonsini invites us to interact with the likeness of a person who too often blends into the landscape—and whose Latino heritage is largely underrepresented in portraiture and in museums.

The activism in these portraits is reiterated throughout the exhibition. And the exhibition itself is touching viewers in unexpected ways. Moss says numerous visitors have emailed her directly to share images of their grandparents and great-grandparents at work.

To offer all visitors a connection to their own story was part of the exhibition’s project from the outset. Yet Moss is still surprised people are making such personal connections.

“I love the idea of people coming here and finding their history and wanting to share their own images with the Portrait Gallery,” she says. “I feel like we should do something with those images now.”

“Charlie Mah-Gow, First Restaurant Owner in Town, Yellowknife, Canada,” Gordon Parks, gelatin silver print, 1945. (The Gordon Parks Foundation)

“The Sweat of Their Face: Portraying American Workers” is on view at the National Portrait Gallery through Sept. 3, 2018.

[ad_2]

Source link